Roadways, once paved, shape cities for decades. In Murfreesboro, an effort began this year to undo a landscape-altering decision from the 1950s.

As was common in many cities, a large road project cut through Murfreesboro. The Dixie Highway — or U.S. 41, or Broad Street, locally — cleared out “The Bottoms,” a flood-prone area home to one of Rutherford County’s earliest African-American residential areas.

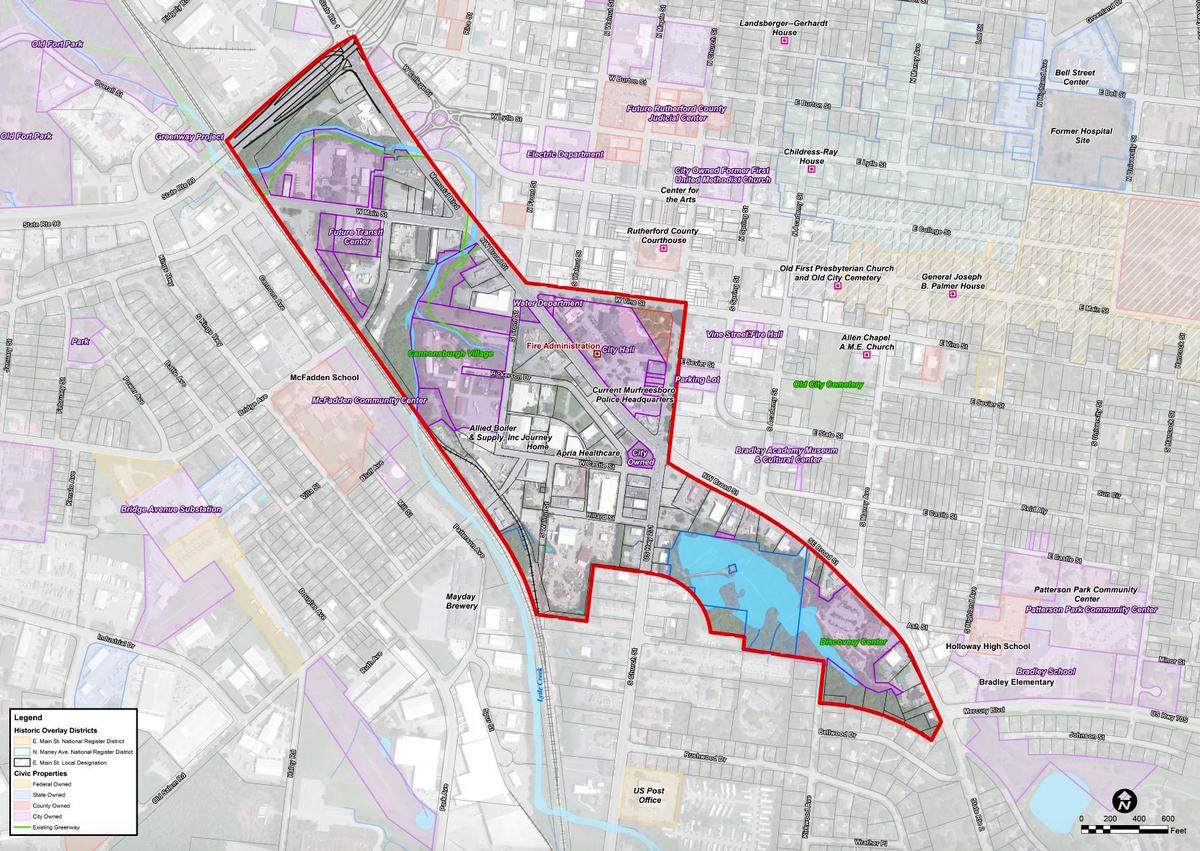

But city officials now see the five-lane commercial drag as an imposing dividing line that has limited the growth of downtown. The road has cordoned off the potential of

The Bottoms, currently home to warehouses, light industry and empty lots.

“We think it’s an area that’s ripe for redevelopment … and it’s an area that probably would not as quickly develop on its own,” said assistant city manager Jennifer Moody. “So we’re interested to see how public investments could encourage redevelopment faster than it would have otherwise happened.”

Moody and a consulting firm say they want to mimic the rebirth of The Gulch in Nashville, which is another enclave in close proximity to a downtown core, but separated, for a time, by geography.

In Murfreesboro,

the redevelopment could mean new infrastructure, robust streetscaping, and a designation as an arts and entertainment district. Zoning could allow taller buildings up to six stories. A pedestrian bridge is part of the conversation that started in March.

‘Every Spring It Would Flood’

This is not the first time the government has taken an interest in The Bottoms.

Back in 1952, federal funds brought a new highway through Murfreesboro, creating the division that exists today.

To understand its cultural impact, the city tapped local historian John Lodl, director of the Rutherford County Archives and

an expert on local African-American settlements after the Civil War.

“A lot of these interstates and major highways went through and cleared out slums, and predominately African-American slums,” Lodl said. “And you see that in every major city in America.”

(

Read a 1956 account of Murfreesboro’s highway project.)

To understand The Bottoms, Lodl led a walking tour for officials and members of Ragan Smith, the land-planning firm hired by the city to re-imagine the area.

Within a block of city hall, the group got a firsthand sense for the challenge.

Broad Street invites no one to cross it.

With starts and stops, the gaggle ventured through an intersection without a pedestrian signal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ye1ln5Eat4k

Once across, two features stand out: Lytle Creek and the rail line that first made the area into an industrial hub, with cotton gins and saw mills. Housing for poor laborers also gathered there.

“From what I’m told, the businesses got worse and worse,” Lodl said. “You got into more of the saloons, gambling kind of areas, coming down off the square.”

The reputation was so rough that one funeral home worker told Lodl that he’d park the hearse there on Friday nights, just waiting for a body.

“They were calling the ambulance all the time. Somebody was shooting up or cutting up all the time,” the late Houston Overton told Lodl in a 2002 oral history. “The only thing I can tell you about it is it was a rough part of town.”

Although few who lived in The Bottoms are alive today, the Overton interview was one of several that Lodl captured for the

Middle Tennessee Oral History Project at MTSU.

(

Read a Daily News Journal feature on one resident.)

Renters stayed in cramped quarters, which were flooded by the creek after almost every rainfall.

“They’d have to move them out in boats or whatever else. Family members would kind of like take them in,” local author Nancy Vaughan says in her recording.

Vaughan, who grew up nearby during World War II, remembers depending on well water, an outhouse and a kerosene stove for heat.

“We didn’t have a bed warmer. So I’d have to wrap up in a blanket and then run as fast as I could to get back to the back and jump in the bed,” she recalled.

The ‘Push-Pull Of Urban Renewal’

When the road project came through, about 40 black families and six white families were moved to new public housing, according to an account from that time.

Eventually, the City Hall complex, a fire station and the water department, would all be built on land once home to African Americans.

The Broad Street project also has a complicated legacy, said Tennessee State Historian Carroll Van West.

“It destroyed a lot of landscape and sort of divided the city,” he said. “But then it did bring, you know, it did work. It brought new business into the city in a major way.

“So it’s that sort of push-pull of urban renewal at the time.”

Broad Street became known for its upscale motels, and drive-in restaurants that made it a popular strip for evening cruising. Van West also credits the project for attracting corporate headquarters, such as State Farm.

“It totally reoriented the city in many ways,” he said.

Van West points out the genuine belief was that Bottoms residents were receiving an upgrade — although they weren’t given much choice.

This time around, there’s been

nine months of public meetings to inform the plan for The Bottoms.