The “digital cleanse” has become a popular challenge at colleges, churches, and fitness clubs, where groups organize specific days to disconnect from technology.

Now, 42 freshmen students at Nashville’s Maplewood High School can say they’ve tested themselves after unplugging from their cellphones for 24 hours.

English teachers Jarred Amato

and Shereen

Cook came up with the idea as part of a broader theme for their classes this year that ask what it’s like for students to come of age in “the Digital Age.”

“A lot of them probably fall asleep to their phone. They fall asleep texting. They sleep next to the charger,” Amato said. “They wake up, the first thing they do is check who called.”

“There’s always a text message to send, there’s always a new picture to see, there’s always a new Snapchat to send,” he said. “They never get a break. And if you ask them, they really don’t like it, but they almost feel powerless to it.”

Amato, still in his 20s, also counts himself and plenty of other adults among smartphone addicts. He can relate to their awesome power. But he at least remembers a world before they were in every pocket.

“If we can replace even an hour a day of screen time with a book, and reading, there’s so much value,” Amato said. “We’re looking at a school here, with Maplewood, a lot of our freshmen come to us below grade level in their reading. And the only way to improve reading is to read more.”

So went Amato’s thinking as he prepared for the one-day event that he titled #PanthersUnplugged. He said he wanted to give his students a chance to reclaim control over their habits, if even for a day.

Panthers Unplug

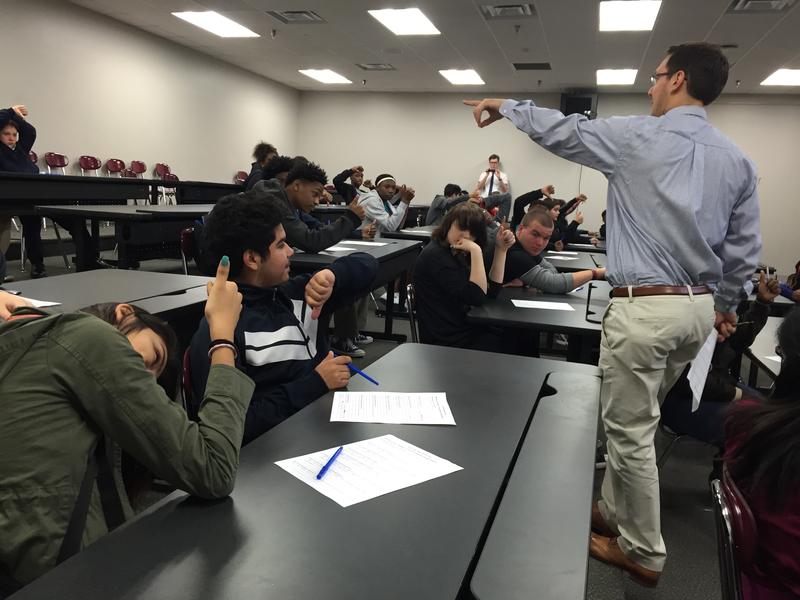

With a student film crew documenting the day, Amato and Cook began by probing the students about how they thought they’d fare and how they’d spend their time while avoiding technology.

“How do you feel when it’s not around — when it goes from 1 percent (battery) and it shuts off and you’ve got no charger and it’s done — how do you feel?” Amato

asked “Do you cry when your parents take it away?”

The answer? A resounding, “yes,” from a few students.

They wrote answers to a set of questions and each wrote the single most important reason that they were choosing to unplug.

“I’m unplugging to figure out who I am without technology, and to focus on myself,” said freshmen Angel Carroll. “I’m always on my phone … always have the camera on myself, taking pictures. I wanted to see what kind of person I would be.”

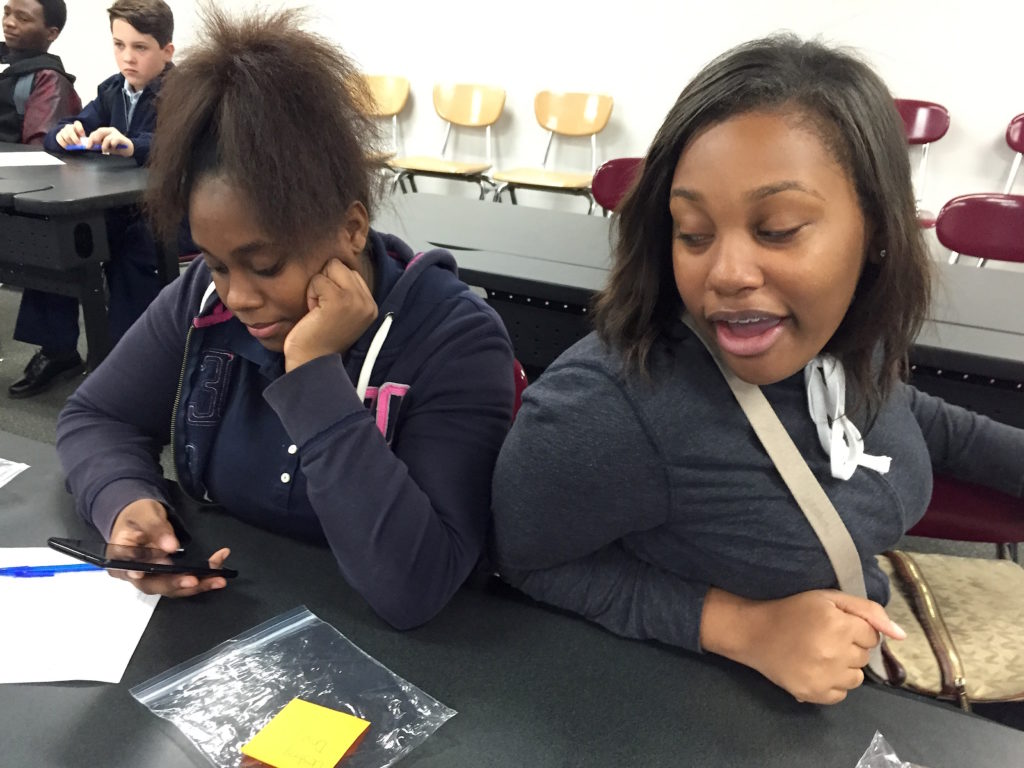

As the clock ticked toward the moment of separation, students Destiny Davis and Jamya

Whitmore

clutched their phones.

Davis said the good part would be talking with her family more.

The bad part? The same.

“Because we’re always communicating on our phones,” she said. “Your family could be in the next room, and we’re texting them, but now you need to get up and go walk to get them!”

When Amato gave the 5-minute warning, panic rippled through the room. The girls had to send their final Facebook messages and Snapchats.

“She already can’t go without her phone. It’s sad,” Jamya said of Destiny. “How we gonna live? I need my phone.”

The students put their phones in Ziploc bags — Amato and Cook too. Then the teachers led the group in the #PanthersUnplugged pledge.

“As a Maplewood freshman, I recognize that many teenagers have become addicted to technology and social media. We are spending more time communicating with our screens than with each other,” the pledge began.

Then, single file, they stacked their phones in a cardboard box. Some even kissed them goodbye.

The phones would spend the night locked in a cabinet. But before Amato could even deliver them, he’d already caught himself reaching into his empty pocket because of a phantom vibration.

Lessons Learned

Fast forward to the next morning, Amato sensed something different in his classroom.

“If you looked at this room yesterday, with their phones, the noise level was a lot lower, because they were just consumed with their phone,” Amato said. “Now, look around, see how many conversations you see. Every pocket of the room looking at each other, smiling, laughing, hitting, flirting, all the normal teenage stuff that I think has kind of been forgotten.”

To milk the moment, he asked the students a batch of follow-up questions while the phones sat just out of reach.

About two-thirds said unplugging was easier than expected — and one student opted to keep her phone off for another day.

Several played outside for the first time in awhile. Others played cards with their families for the first time in years.

And almost universally, those who unplugged went to bed earlier, although Destiny and Jamya said that waking up without a phone was disorienting.

“My hand went to my pocket probably a hundred times,” Amato said. “That moment where you think it’s missing, but then you realize where it is. So that happened a bunch.”

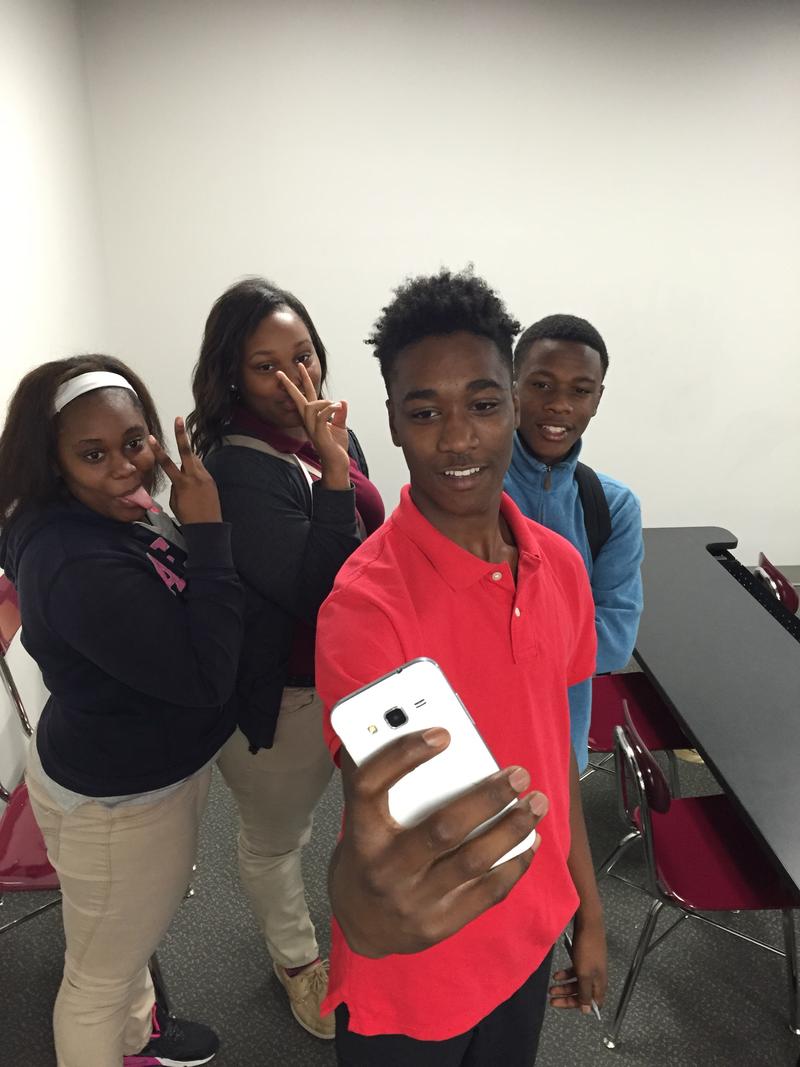

And then at long last, on Amato’s

count of three, they tore the bags open, with woots

and a fresh round of cellphone

kisses.

The first order of business: Count up the missed messages, “likes,” Snapchats, and Kiks. Jamya had at least 15, and Destiny immediately began exclaiming about the gossip she’d missed overnight on Facebook.

Amato had missed a lot too: “71 emails — 63 from Gmail, eight from work.”

It turns out those phantom vibrations they’d been feeling for a day — messages were coming in over that time. And they were still there, waiting to be read, after everyone had unplugged to live a little.