More than a decade has passed since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the so-called “sodomy” laws that made it criminal to engage in homosexual sex — and even longer since Tennessee took that step.

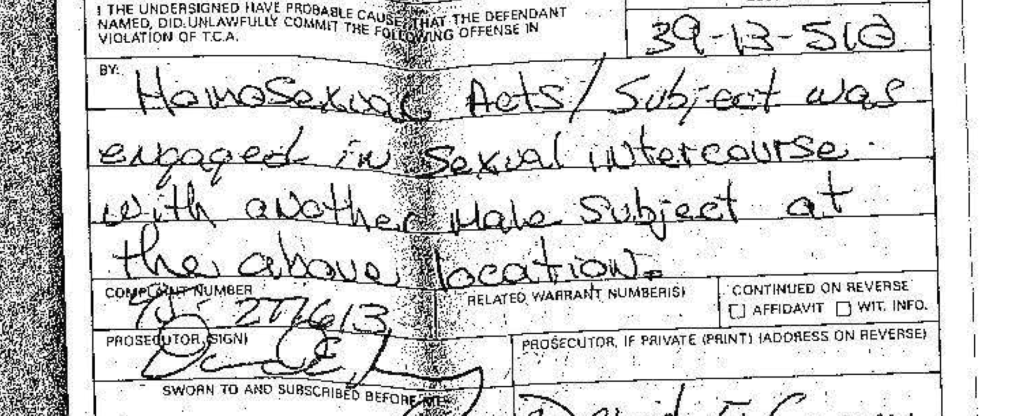

Yet traces of those prosecutions linger, with charges logged in court files and subject to background searches. In Nashville, that includes convictions against 41 men from the 1980s and 90s.

That count,

first reported by Slate, came to light this summer when a man sought out local attorney Daniel Horwitz for help with expungement — the clearing of his criminal record.

“That conviction, once I pulled the file, was a 1995 misdemeanor conviction for homosexual acts,” Horwitz said. “It’s extraordinary to most people that these prosecutions even occurred at all … but this gentleman had a problem.”

Horwitz had not seen such a case and was surprised to find one from 1995, one year before Tennessee ended its Homosexual Practices Act.

The man had been issued a citation for something that took place in his South Nashville apartment. He went to court. Pleaded guilty.

These days, he is identified only as a John Doe, and he declined to be interviewed. Horwitz said the man worries about being outed, and sought legal help before applying for a job.

“Criminal convictions follow you,” Horwitz said. “Somebody pulls a criminal background check and it doesn’t come back completely clean, people are often ineligible for housing, ineligible for employment, and discriminated against.”

For Horwitz, expungements are routine. But for this request, the passage of so much time seemingly left no legal path. The fact the state and U.S. supreme courts had struck down sodomy laws was not enough.

“So we had to dust off the textbooks and find a new way to move forward,” he said.

‘Consistently Criminal’ For 1,500 Years

In recent years, the run of victories for gay rights can make it hard to imagine the criminalization of homosexual acts.

But history shows just how ingrained such thinking has been, says Eric Berkowitz, a human rights lawyer in San Francisco and author of “The Boundaries of Desire,” a history of sex laws.

“Sex, for whatever reason, triggers laws or ideas of justice and rehabilitation that are different,” he told WPLN. “The law is ready to deal with sex transgressions very harshly.”

Criminal law, he said, has followed perceptions of homosexuality as a mental illness, or a disease. Sodomy laws began to fall quickly in the 1970s.

“For those laws to be unwound so quickly is absolutely dazzling,” Berkowitz said. “But often times, laws change as the result of very tireless work of advocates.”

Tennessee repealed its Homosexual Practices Act in 1996, followed by a similar U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2003, in

the case of Lawrence v. Texas.

‘Ingenious’ Legal Idea

To pursue expungement in 2016, Horwitz had to tap into legal thinking not often practiced these days.

His ah-ha moment was hitting on an old common law doctrine, the writ of “audita querela,” which hadn’t been successfully used in a Tennessee courtroom in at least a century, he said.

With finesse, that approach got his case to a judge.

Where he next found help was also unexpected.

Glenn Funk, the Davidson County district attorney, said he was struck by Horwitz’s “ingenious” approach.

And he reacted strongly to the premise of the original conviction.

“I do not believe that people should be punished in a criminal prosecution based on the way they were born,” Funk said. “In 1995, the police department was enforcing a law that had been enacted by the Tennessee legislature. In 2016, we have the opportunity to correct a wrong. And we’re doing that.”

Judge Melissa Blackburn ordered John Doe’s records expunged, and as of this month, the court clerk is shredding the physical copies and clearing them from an online database.

Still, similar convictions remain against 41 other men — including some that were brought later than the 1996 repeal of the Homosexual Practices Act, according to Horwitz.

The prosecutor said he alone can’t clear those names. But he said he will support anyone who pursues the unusual legal path to expungement that’s now been forged.

Meanwhile, there’s been an initiative in Nashville to inform more defendants about expungement. Specifically in cases in which charges are dismissed, judges have been asking defendants if they want records of the arrest erased, Funk said.

Learning of the case from the outside, Berkowitz, the California attorney, said he sees a deeper importance than expunged criminal records.

“Where the expungement … will probably not do a lot to change the lives of these gentlemen in Tennessee, or elsewhere, it does signify a very very powerful shift in terms of the law setting the tone for what the rest of us think is right and wrong,” Berkowitz said. “It’s, in effect, a declaration by the state of Tennessee … that we no longer consider this wrong.”