Editor’s note: On Friday night, a judge postponed Matthew Charles’s hearing. See the update here.

Last year, a Nashville man got an unlikely chance at redemption.

Matthew Charles walked out of a federal prison a decade before the end of his term, after the Obama administration reduced the minimum sentence guidelines for dealing crack. He has spent the past year and a half rebuilding his life.

But now in a rare case, a higher court says he needs to go back behind bars.

During that year and a half, he’s spent almost every Saturday morning volunteering at a food pantry in North Nashville — unloading donations, chopping vegetables and organizing shelves.

Many of the volunteers at the “Little Pantry That Could” are young men on probation or parole. Once their community service hours are done, they almost never come back, says Stacy Downey, the nonprofit’s founder.

But Matthew Charles has. Every Saturday, rain or shine. Downey says she’s come to depend on him.

“He is the best at connecting with these young men,” says Downey. “He targets who needs a little bit of work and who needs a little encouragement.”

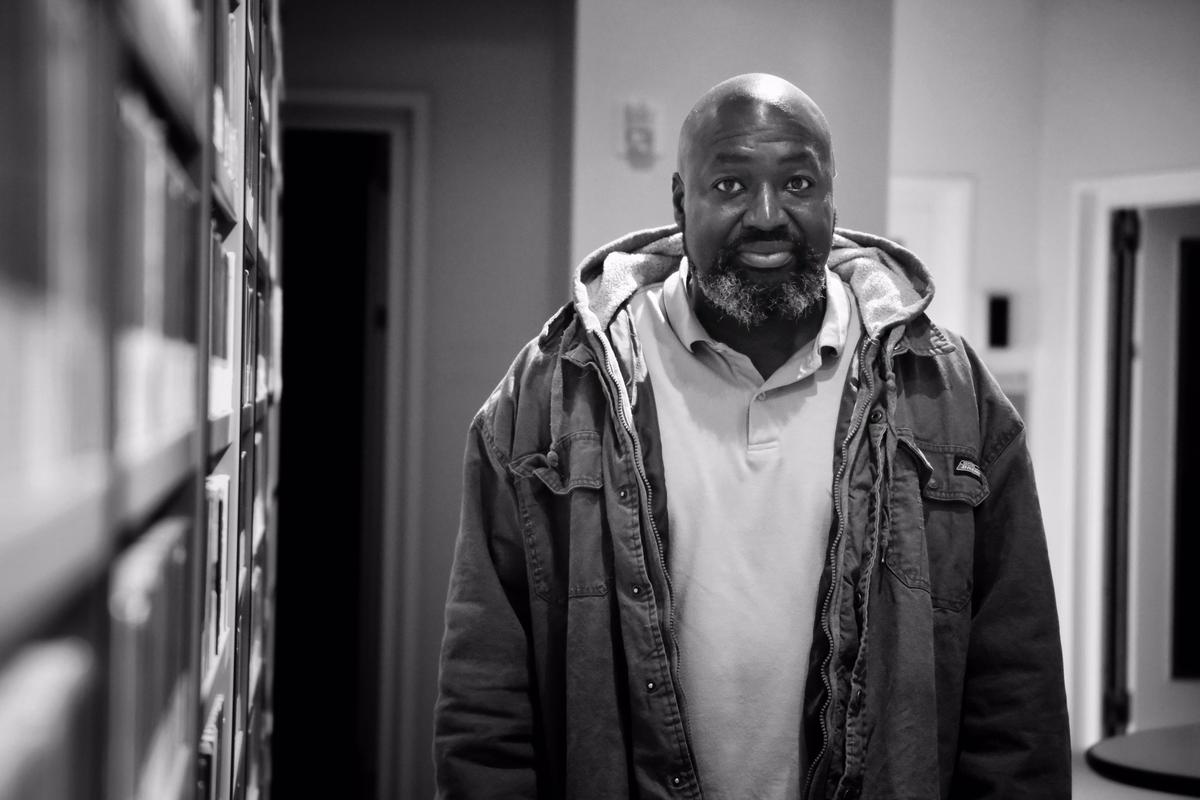

Charles is soft-spoken and reserved but has an undeniable presence at the pantry. He’s 51, bald with a graying beard and fit from daily workouts.

But lately Downey has been worried she’ll lose him too, because Charles might be going back to prison.

“It makes me feel sick just to think that he might not be here,” says Downey. Slumping into a worn chair in a cramped room out back, she begins to cry.

‘Hard As a Stone Wall’

The compassionate man Downey knows is very different from the young man who grew up in Southside Village, a public housing complex in Lexington, North Carolina.

“I was completely numb, probably from the age of 12 until that 29,” says Charles. “I was probably hard as a stone wall.”

Charles says his home life was chaotic.

“All of my behavior kind of mimicked my father’s behavior. That’s how he treated my mother, that’s how he treated us. She got pushed and slapped around like a rag doll. All my childhood I was seeing that. But I said I’d never be like that. And I ended up being a worse version of him…if not a carbon copy.”

Looking for a way out of the projects, he joined the Army. But Charles says he struggled with authority. He grew angrier, eager to rebel. After he was honorably discharged, he returned home — back to square one.

It wasn’t long until he ended up in state prison. He was convicted on a rack of charges, including kidnapping and assault.

By his own account, Charles in his early 20s wasn’t a good guy.

He had started dating a girl, but things weren’t going well. He was becoming abusive like his father, and she decided to leave him. Twice Charles made her get in his car, hoping to force her back home. Later, after he was picked up on kidnapping and assault charges, he ran away when a detective left him in a room alone with an open door.

Charles said he bolted, then panicked. He didn’t know what to do or where to go. He picked up a gun and tried to steal a car. But the man he tried to carjack wouldn’t give up the keys and a struggle ensued. His gun went off. Charles swore it was accidental, but it was too late. The man wasn’t seriously injured, but the bullet grazed his head. It was over.

He served his time and was paroled. Then, he moved to Clarksville and began selling crack. One of his clients was a soldier at nearby Fort Campbell. When that man was caught, he made a deal to turn in his distributor: Matthew Charles.

30 Years To Life

In 1996, he was found guilty of seven charges related to the distribution of 216 grams of crack cocaine. There were also weapons charges because Charles, a felon, had obtained two guns under an assumed name.

At trial, prosecution pointed to his criminal record. They labeled him a “career offender.”

Though the War on Drugs is still far from over, at the time, the crack-to-cocaine ratio was 100 to 1, meaning that possession (or distribution) of just one gram of crack carried the same punishment as 100 grams of cocaine — even though they’re two forms of the same drug.

Later, experts would testify that this resulted in disproportionate mass incarceration of low-income African American men. During this period, black men on average served longer sentences for non-violent crimes than white men for violent ones, according to the ACLU.

In 1995, just months before Charles’ arrest, the U.S. Sentencing Commission acknowledged a disparity in sentencing, but Congress refused to act. So when Charles stood before a judge, mandatory sentencing guidelines for crack meant he faced 30 years to life.

“I got sentenced 35 years,” says Charles. “I was heartbroken, didn’t understand it. Ten was too short, I thought I’d get 20 years. I deserved to be in prison, I just didn’t expect it to be so long.”

But while awaiting trial, an inmate he’d befriended left him a Bible the day he was deported. Alone in his cell, he began reading. It was the start of his spiritual awakening. One night, he says he reluctantly spoke out to God.

“I was like, ‘Well, if you’re real, you’re going to have to kind of prove it because I hadn’t experienced you in no part of my life,’ ” says Charles.

“I just started weeping and crying and it felt good. It just cracked the shell.”

All of a sudden, Charles could feel. And he says, what he felt was the weight of everything he’d done wrong.

Making Amends

In the two decades that followed in prison, Charles rebuilt himself. Within the first five years, he completed more than 30 Bible correspondence courses. He taught GED classes, worked on a college degree and became a law clerk. He followed legal changes closely, helping other inmates and filing countless briefs in his own case. He also read old books that were donated to the chapel and worked out to stay sharp. He received no negative marks on his discipline record — ever.

If the federal system had not abolished parole, he might have been a perfect candidate. But the Department of Justice did away with sentence reductions for good conduct more than a decade before his arrest.

Then, in 2010, the Obama administration reduced minimum sentences for offenders like Charles. Kevin Sharp, the federal judge who reviewed Charles’ case, said he looked over old transcripts to determine whether the original judge based the sentence on the crack guidelines or his status as a “career offender” — an important distinction because sentences for career offenders haven’t been reduced.

“The way I read it, I thought that he was eligible,” says Sharp. “No doubt was a close call, but I thought that you couldn’t discount was what had happened while he was in prison. I also thought that was important. He had really reformed.”

Sharp reduced Charles’ time by nine years based on the new crack guidelines. In 2016, Charles was paroled to a halfway house. He was finally free to build the life he’d envisioned behind bars.

Starting Fresh

Shortly after his release, he met Naomi Sharpe. He was honest about his past, which she appreciated, but she was still cautious. Their relationship developed over the phone — “like high schoolers,” she jokes. Charles would call her every night as he walked back to the halfway house from his job at a record store.

“I was looking for some sign that he’s not real, that he hasn’t changed his life around,” says Sharpe. “Cheating somebody at the store, just something, I was looking for something. But there’s wasn’t anything. And actually, he was making me a better person.”

She says he was observant and thoughtful — as he walked through the streets of Nashville with Sharpe at his ear, he marveled at the lights in the towering buildings, the crispness of the air, the way distracted drivers rode past homeless men and women on street corners. She liked that he volunteered at the food pantry every Saturday. They began going to church together on Sundays.

After he was released from the halfway house, Charles rented a room in East Nashville, got a job as a driver and bought a car.

“I was making minimum wage money and I was doing it the right way and it felt good,” says Charles. “It felt like an achievement. It was an achievement.”

He slowly began piecing his family back together. Through Facebook, he even found out he had a second daughter — and grandkids. They just spent their first Christmas together.

The Appeal

But the government appealed his release on grounds that Charles was a career criminal. The prosecution declined to comment but in documents filed with the court, they say the new, more lenient guidelines did not apply to him. And the U.S. Court of Appeals agreed: they said Charles should return to prison and finish his sentence.

His lawyers argued that it’s unnecessary and cruel to put Charles back in prison. They even asked the Supreme Court to weigh in on his case, but they refused.

A recent filing is littered with letters of support from members of the community and local organizations that have worked with Charles.

Another consideration is the cost to taxpayers, his attorneys say. Another decade behind bars could cost more than a quarter million dollars.

Cases like this don’t happen often. Mary Price, an attorney for the advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums, can only think of one recently. A man in Orlando whose mandatory term under state law was reduced but later reinstated.

She says the current justice system is designed to punish not rehabilitate and points to Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ recent order that prosecutors seek the highest possible charges.

“To the American public, to individuals who are trying to rebuild their lives, it sends a terrible message that it doesn’t matter what you do, it doesn’t matter how well you behaved in prison, how well you’re doing on the outside, that this cookie cutter justice is going to come get you,” says Price.

So, on Jan. 4, Matthew Charles will stand before a judge for a final hearing. The outcome seems inevitable — he will most likely be ordered back to prison.

But Charles says he is not defeated. Twenty-one years ago, a miracle made a cold man want to change.

Two years ago, it set him free.

Maybe redemption comes in threes.

More on the case of Matthew Charles:

- As He Heads Back To Prison, A Nashville Man Says ‘Goodbye’ To The New Life He Hoped To Build (May 2018)

- How A Nashville Man’s Name Became One Of The Rallying Cries For Prison Reform (June 2018)

- Matthew Charles, Nashville Man Who Gained National Attention, Is Released From Prison Again (Jan. 2019)

- After State Of The Union Spotlight, Matthew Charles Goes Full-Time On Criminal Justice Reform (Feb. 2019)