The dedication page reads: “For those officers who want to win.” The book, written by former journalist Charles Remsberg, was published in 1986. With gritty black and white photographs and tabloid-esque writing, it depicts a world of constant and increased threat. And it prescribes an aggressive approach to policing at a time when Nashville’s department, and many around the country, are trying to move the other way.

The Metro Nashville Police Department says the most contentious material in the book is not taught. But some policing experts say the entire book, with its 31-year-old statistics and racially charged undertones, has no place in today’s law enforcement training.

“It’s important for people know going through the academy that this is a dangerous job they’re getting into, but the first images in the book are of dead police officers,” says Matthew Barge, the co-director of the Police Assessment Resource Center, which helps departments across the country on reform initiatives. He’s referencing the black-and-white photo of five dead officers on page one of the introduction. It’s followed by pictures of black men in prison and a teenager jumping on a police car.

Barge scrolls through the book’s introduction where, in all caps, it lays out the “cold hard bottom line: The gap between the training you get spoon-fed and what you need to survive on the street is left up for you to fill.”

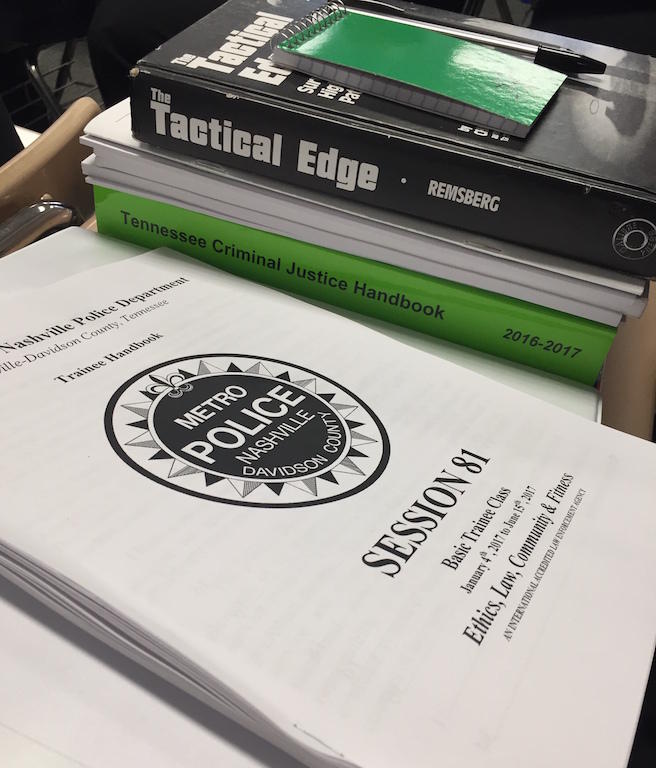

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNOn day one of training, every new recruit in the Nashville Police Academy is issued a stack of reading materials. Right on the top is Tactical Edge, a textbook dedicated to high risk patrol.

“That’s, like, red flags all over the place for me,” Barge says, after reading the line aloud. Barge is also the court-appointed monitor overseeing the federal consent decree between the Department of Justice and the city of Cleveland.

The book tells officers to be wary of an increasing population of minorities, which it says are “disproportionately associated with criminal violence.” It claims that public schools are churning out kids with criminal tendencies and that preschoolers left in day care are 15 times more aggressive than other children. It also says that most police training will

always fall short of what’s really needed.

It sums the chapter up with these words: “On the street you will meet the human beings, the weapons, the mentalities behind the dismal facts above. They are waiting for you. Either you or they will have the edge.”

The type of mindset and culture Tactical Edge espouses, Barge says, “can be very damaging” and “create the kinds of problems that troubled police departments throughout the country have gotten into” — problems like racial profiling and the abuse of police authority.

An excerpt from Tactical Edge, published in 1986.

Capt. Keith Stephens, who’s in charge of the Nashville Police Academy, says the department uses only some sections of

Tactical Edge for topics like crisis response, stress management and mental conditioning. He adds that it’s augmented by more than 200 hours of academy training.

“I don’t believe [the book] is controversial,” Stephens says. “The part that you are talking about is not what is instructed by the Metro Nashville Training Academy.” Stephens recalls being issued the book when he went through the academy back in 2002. Nashville Police could not tell WPLN when the book was first used in the academy curriculum.

But these days, the training protocol of many police departments around the country, including Nashville’s, is being scrutinized as they wrestle with police-involved shootings and race-related criticisms.

In November, a Nashville study found that black drivers are stopped significantly more often than white drivers. The same study, which has now been characterized as “morally disingenuous” by the police chief, also found that officers are more likely to try to talk their way into a vehicle search for black drivers, even when there’s no obvious cause for one.

Less than three months after the study was released, a white Nashville Police officer fatally shot a black man, twice in the back and once in the hip, after approaching him for a traffic violation. The man, Jocques Clemmons, allegedly had a gun. The officer, Joshua Lippert, had a lengthy disciplinary record that included a number of suspensions for use-of-force violations.

An excerpt from Tactical Edge, published in 1986.

Capt. Stephens defends the book. But after reading him one excerpt, claiming minorities have a higher rate of criminal behavior, he starts to backtrack. He acknowledges that it might be worth reconsidering the use of

Tactical Edge in the academy’s curriculum, which he says is always evolving.

“Can I look at this book and say there may be better books out there? Sure, there may be better books out there,” he says. “I think that we should constantly be evaluating what we are teaching and where we’re teaching from.”

But experts say it has no place in police curriculum.

“A book like this should not be issued to recruits, period,” says Michael Lyman, a professor of criminal justice at University of Missouri and an expert in police procedures and training. He says he’s never encountered

Tactical Edge as academy-issued reading. “Issuing them a book that is 30 years old gets them started off on the wrong foot,” Lyman says.

In other words, while the department is training officers to be guardians of the public and de-escalate situations, it’s also handing them information that teaches them just the opposite. The mixed message, Lyman says, can lead officers to make serious, if not fatal, mistakes in the field.

Follow-up:

Nashville Police Academy Will Stop Using Racially Charged Textbook