The dawn of civilization can be traced back roughly 400 generations. That means there are roughly 400 mothers between you and the beginning of human history.

But, for former Youth Poet Laureate Alora Young, that trail goes cold after just seven generations.

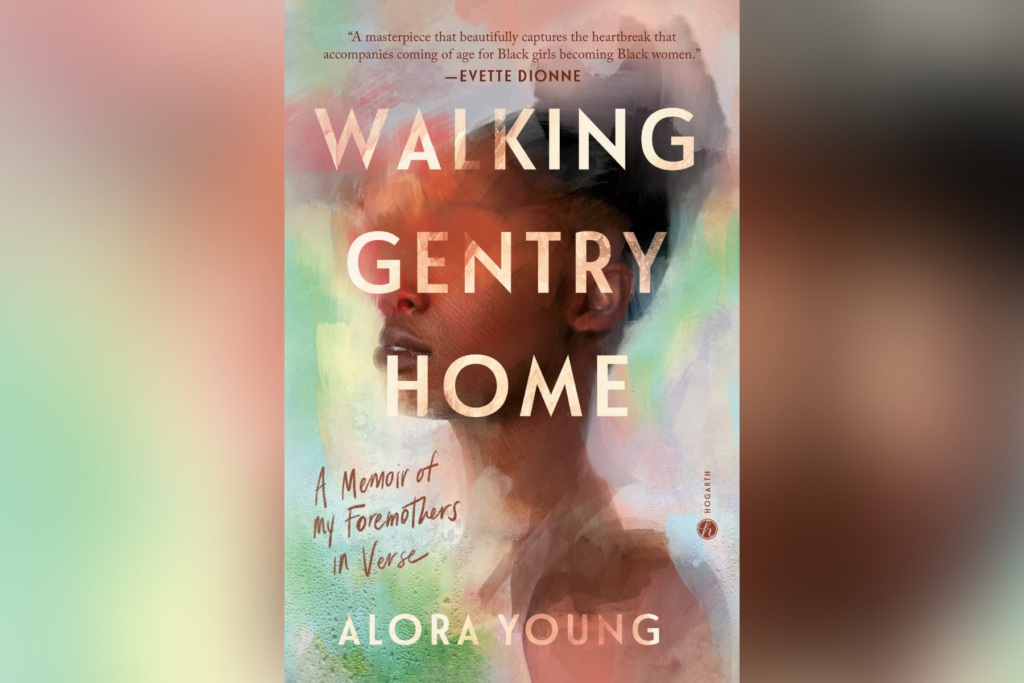

Her debut poetry book chronicles the lives of the seven women in her maternal line who she’s able to name. Afternoon host Marianna Bacallao spoke with Young before the release of her debut, “Walking Gentry Home.”

Black womanhood

Is being asked to bring gifts to parties you were never invited to

It’s lighting everyone’s candles with the fire alight in you

It’s standing in solidarity with women who didn’t fight for you

Because you know what oppression feels like

And I think that God just might

Love

Like Black women do.

— “To Have a Name,” Alora Young

Marianna Bacallao: Now, Alora, in this family memoir, you’re reaching up your maternal line and telling the stories of the women in your family that haven’t really been told. I imagine finding firsthand accounts must have been somewhat difficult. How did you go about doing your research?

Alora Young: So, I dug through archives. I went to the library and read old newspapers. I interviewed every living member, every living female member of my family for this book. And, through the historical records, I found out these little details about them. Like I found out, “Oh, she was freed at this time.” And then, I found a will. And, I read this will, and it refers to her by name — my great, great grandmother, by name, in a will to his daughter.

MB: Wow. Aside from the research that you did, what were the sorts of stories that you grew up hearing about the mothers in your family?

AY: Of course, the titular “Walk Gentry Home” story. That was one I always grew up hearing. And, it’s the story of how my grandmother, Gentry, got pregnant at 14, and she got married and went to live with her husband, my grandpa, Walter D. And, one day, she got so mad at him that she walked all the way back to her family home in Haywood County. Her mom let her stay for a little while, and she hangs out and plays jacks with her brother. And, eventually, she says, “Mama, I need to come home. I want to come home.” And, her mom says, “Okay, Ortho B, walk Gentry home.” And, just to realize that the home you grew up in is no longer the home you belong to. Every girl eventually learns what that’s like when you realize that you are no longer a part of the home that raised you, and you are now a part of the home that you make.

MB: So, you talk about this transition from girlhood to womanhood and how that change is very different for black girls. When does womanhood begin?

AY: Womanhood never really begins because girlhood never really ends. While the world will see us as a woman before we’re ready, it takes longer for us to see ourselves as women because we never get the chance to be girls.

MB: You also write a little bit about how motherhood plays into that timing of when the world starts to see you as a woman. But, you also talk about how vital mothers are — you know, how the world is built on their sacrifices. How do you see the mothers in your own family carry that burden?

AY: I mean, making a home is like doing artwork. You’re crafting a cradle for the next generation for them to feel at home there. And, it doesn’t ever really belong to you. You make it, and you love it, and you nurture it until it’s ready. And then, it belongs to the world. Like this book, it doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to the world.

MB: You’re also playing with this idea of home and what home really means, while also coming back to Halls, Tenn. That’s where your great grandmother, Nannie Pearl, first became a landowner. And, the way you describe it, it sounds like a place that exists outside of time. I know you grew up in Nashville, but is Halls still home?

AY: Halls is, has always been and forever will be home. And, while my day-to-day life happened in Nashville, Halls is where my heart has always been. Because … the concept of home is sort of a fallacy in that you build a home, and you leave a home. But, as a woman, you never really belong to a home. Halls, because it’s been in my family for so many generations, is as close to a true home as a woman ever gets. That’s not where you live. That’s where you come from.

MB: That’s Alora Young speaking with us about her debut collection of poetry. Alora, thank you for being with us.

AY: Thank you for having me.

“Walking Gentry Home” is out in paperback Tuesday.