Inside the Looby Community Center gym, a group of elementary schoolers file into the airy, blue space. Some kids lob basketballs across the court, others sling hula-hoops around their waists. It’s a warm night, but the temperature inside is cool, thanks to a new air conditioning unit. It’s an update that the community desperately wanted for years and that was finally funded by winning one of the public votes through Nashville’s participatory budgeting project.

It’s a process that allows residents to have a say in how millions of government funds are to be spent.

Ambria Berryhill, who works at Looby, says it’s almost too good to be true.

“You get all this money that’s supposed to go into my community and all I have to do is X, Y, Z?” she says “But it really is that simple!”

Cynthia Abrams WPLN News

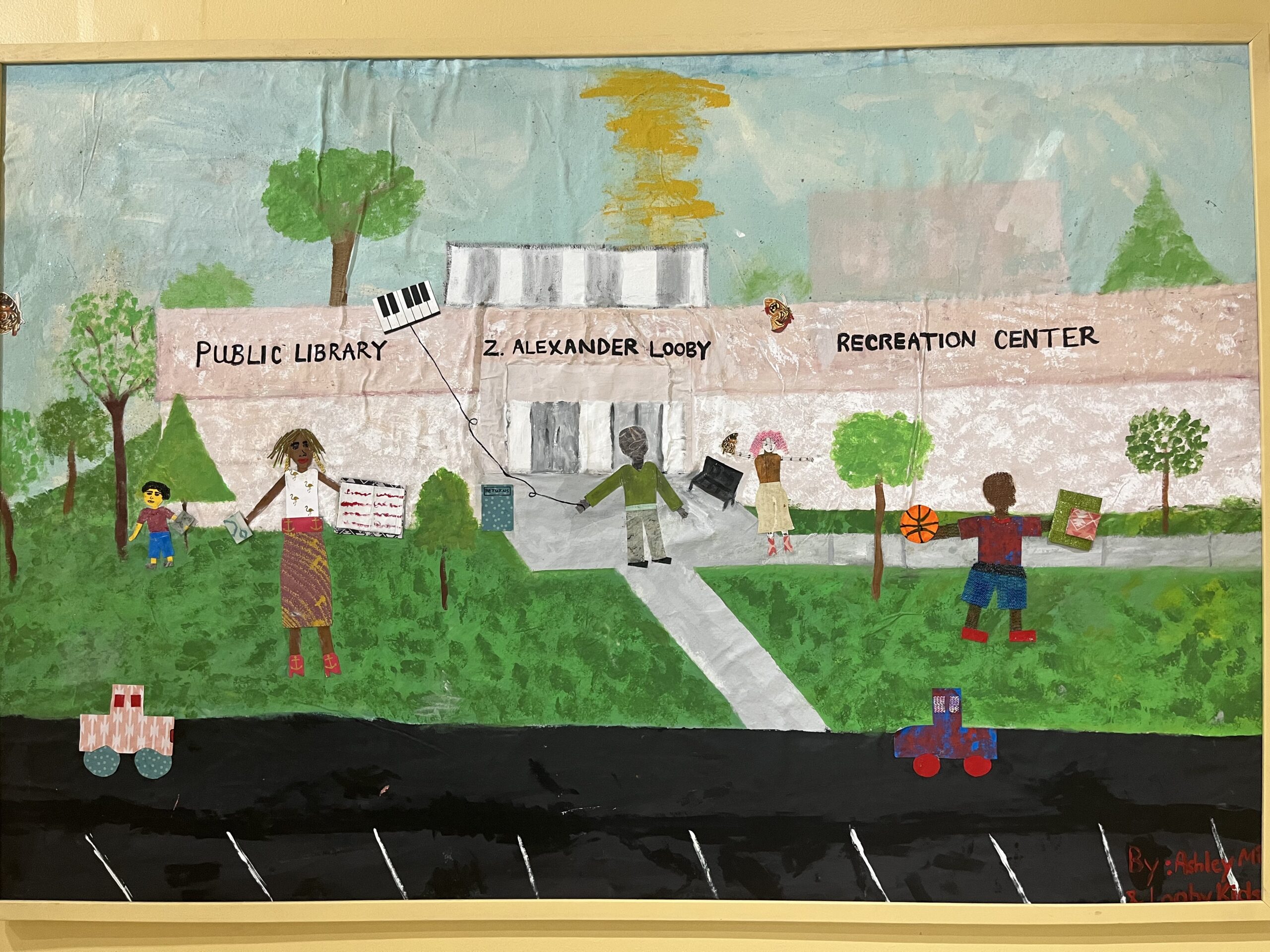

Cynthia Abrams WPLN NewsA painting in the Looby Community Center. Looby has been the recipient of funds in two rounds of participatory budgeting.

At the time that Looby received funding, only certain neighborhoods — North Nashville and Bordeaux — got to vote on how this slice of their tax dollars would be spent. Now, Nashville has opened up $10 million dollars across the entire city.

There are 35 nominated projects in all, marking one for each Metro Council district. Projects were selected from over 1,300 submissions and range widely in cost: some would require as little as $50,000 while others are asking for over $1 million.

Voters can choose from things like swing sets in East Nashville, speed bumps off Trinity Lane, an apprenticeship program through local colleges. Projects focused on traffic calming and park improvements are the most common.

All residents age 14 and up — regardless of housing status or citizenship — can vote for their top five, and the most popular will be funded. Ballots can be cast at PBNash.com, or at any library branch, until results are tallied on Nov. 30.

Jason Sparks, a volunteer who has committed countless hours as the chair of this year’s steering committee, says that the process is a way to see direct action on an expedited timeline.

“A lot of the ideas that were submitted and are on the ballot are things that could have taken five, ten years to execute with the current bandwidth,” Sparks says. “But the fact that these get prioritized, I think it’s a great way to to hear those direct voices and not necessarily the lobbyists or the, you know, big companies getting contracts.”

Sparks says participatory budgeting has restored his faith in “what the government can do.”

The process is meant to empower residents to have more of a say over their tax dollars. And because it’s powered by COVID-relief funds (this round, at least), it’s also intended to help the communities most hurt by the pandemic.

One way it does that is through a “Social Vulnerability Index,” which considers things like socioeconomic status and race. After votes are tallied, those factors will help guide how much money the winning projects receive. This speaks to one concern about the process — that the most in-need projects might not receive funding.

“It’s what keeps me awake at night,” Sparks says. “And I think, you know, the joke that we had going into all this was that if we ended up with a pickleball stadium in Belle Meade, we all failed.”

That’s one reason why increasing awareness about the program, and opening access to the voting, is crucial. But, as voting wraps up, totals show all is not well. The online tally (which doesn’t include mail-in and ballots from library branches) so far is under 10,000 ballots — even though the entire city is now invited to participate.

Why the low turnout?

Sparks thinks it has to do — at least partially — with the departure of Fabian Bedne from the mayor’s office.

“He kind of put, you know, a roadmap in place,” says Sparks. “But nobody’s reading that roadmap right now, regrettably.”

With the turnover that comes with a new mayoral administration, Bedne was left without a job — and participatory budgeting was left without one of its most vocal champions. Bedne declined to comment.

Things are still in flux: Mayor Freddie O’Connell has been open about some misgivings he has with the current approach.

“Many of those things, we made people who don’t get capital investments routinely do extra work to get less money,” O’Connell said. “And that doesn’t feel like the aim of participatory budgeting. And that’s the part I want to go back and revisit.”

This a common complaint — making residents go through a process for projects that deserve funding.

But, even with the concerns, supporters like Metro Councilmember Zulfat Suara are adamant that participatory budgeting needs to continue.

“People do not trust the government. People feel like the government is not listening to them,” Suara says. “Participatory budgeting allows us to put our money where the people need it.”

Suara says that even though the funded projects often go unseen — a playground here, a bus shelter there, or an air conditioning unit for a community center’s gym — they are the projects that communities say they need. And that is what makes it an important “democratic tool.”

Correction: This story originally gave the incorrect comparison for participatory budgeting vote totals in the past two years. This year’s totals have exceeded prior cycles.