Not everyone who uses Nashville’s transit system lives within the city — and more than 200,000 people commute in every day from neighboring counties.

That commute isn’t always easy. There’s bumper-to-bumper traffic, crashes and seemingly inexplicable slowdowns.

“It’s just time spent in their car that could be time spent making money, or with their family, or having fun at a park,” says Michael Skipper, the executive director the Greater Nashville Regional Council. “And, eventually, it will begin to hurt our economy because jobs or employers aren’t going to want to do business in a region where their workforce is having a hard time getting to work or their customers can’t get to the business.”

While Davidson County voters will be deciding on a major transit overhaul this fall — one that proposes things like bus-only lanes, better bus service and upgraded traffic signals — those changes won’t extend into surrounding counties.

Yet some neighboring leaders are still quick to endorse the plan, saying it’s the right step toward regional connectivity.

“You can’t just come out of the box and be regional,” says Clarksville Mayor Joe Pitts. “The nucleus of Mayor O’Connell’s plan is to start inward and branch out.”

Skipper echoes that starting in the city is logical, given the regional significance of Nashville. He says that what’s being proposed can be thought of as a “starter line.”

“Anything that happens in Davidson County, it’s regional because it can be extended,” he says.

Beyond the urban core

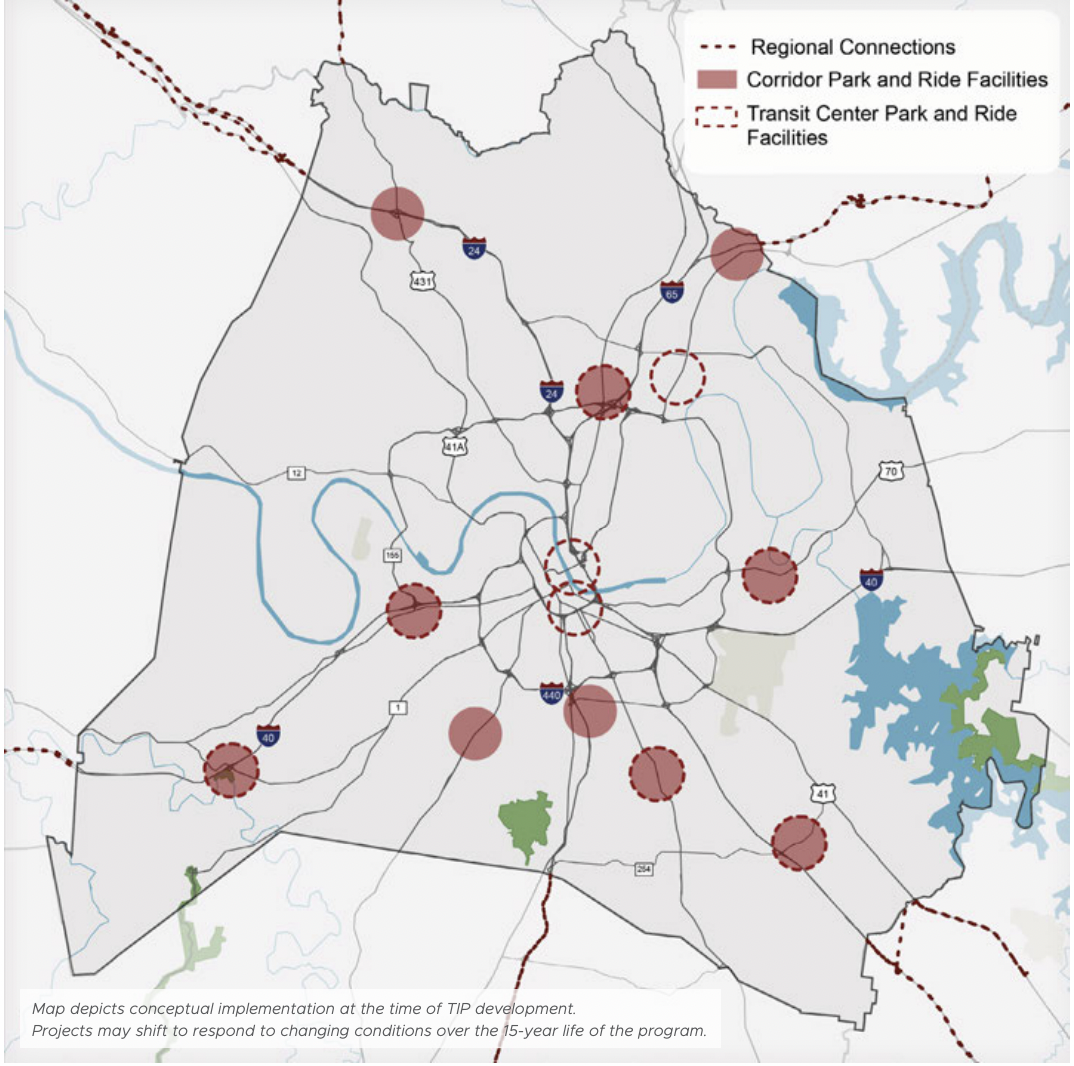

The plan presents various places where neighboring counties could plug-in and extend transit service — such as 17 park-and-ride facilities, where commuters could leave their vehicles and finish their commutes via bus. Some would be located on the outskirts of Nashville, and the plan also floats the possibility of establishing longer-distance routes out of these facilities.

There’s also express routes from the four corners of the county, as well as service adjustments to the WeGo Star, which, as Middle Tennessee’s only cross-county rail line, connects Nashville with communities to the west, out as far as Lebanon.

In 2018, the last time Nashville attempted a transit referendum, some opponents claimed it wasn’t regional enough (though numerous regional leaders did express support).

There’s significant regional backing again this year. The Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) — a board of county and city mayors across ten counties, plus state appointees and a TDOT representative — endorsed the plan in June.

The first domino

Although the regional offerings are scant compared to the myriad upgrades proposed within Nashville, some leaders feel improvements within the city could benefit their constituents.

“Once you get to Nashville, it’s equally frustrating that you get there and you kind of come to an abrupt stop,” Pitts says.

And there’s agreement from Wilson County Mayor Randall Hutto, who also serves as the chair of the RTA.

“I can send my people to Nashville, but they’ve got to have a way to get around,” Hutto says. “So whatever is being done in Nashville to move people from point A to point B, to me, makes it regional.”

There’s also the possibility that, if Nashvillians decide to approve the dedicated transit funding, other counties could follow.

“You’ll see subsequent efforts in the surrounding counties to follow that policy,” Skipper says. “The projects may look different. The funding source may look different. But ultimately, those investments will tie into the steps that Davidson County would be taking after November.”

To fund the proposal, Nashville is asking voters to approve a half-cent sales tax increase. The referendum is set to appear on the Nov. 5 ballot.