This article was produced in partnership with ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

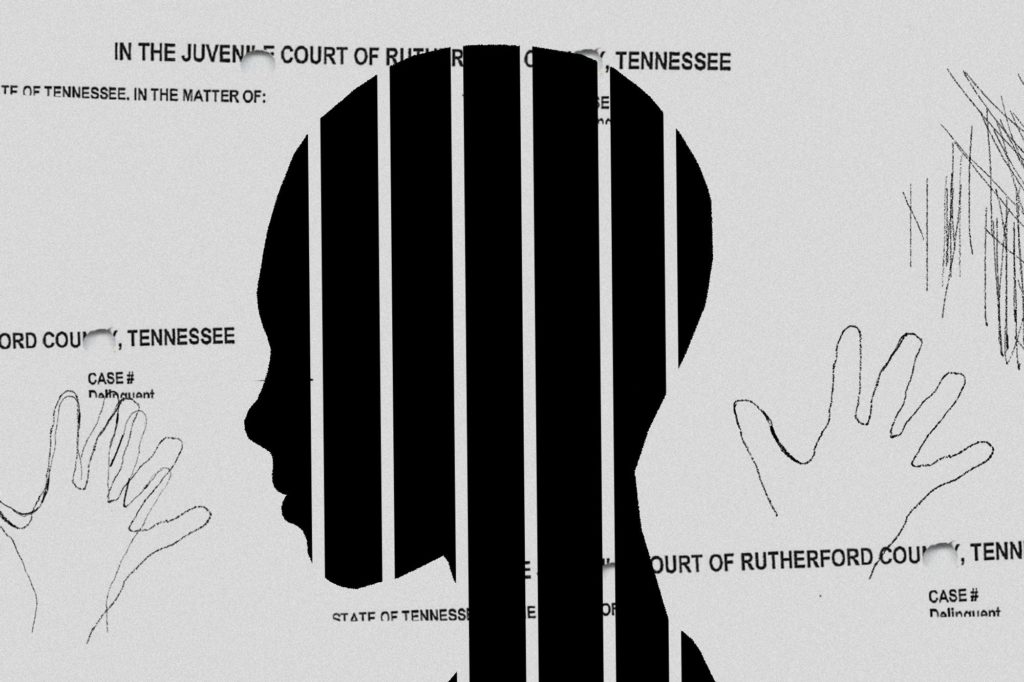

Tennessee’s Rutherford County, which has been widely criticized for its juvenile justice system, has been jailing Black children at a disproportionately high rate, according to newly obtained data. And, in a departure from national trends, the county’s racial disparity is getting worse, not better.

In an earlier story, ProPublica and Nashville Public Radio chronicled a case in Rutherford County in which 11 Black children were arrested for a crime that does not exist. Four of the children were booked into the county’s juvenile jail.

Since publishing that story, the two news organizations have received reports from the Tennessee Commission on Children and Youth. This data shows that while the county was locking up so many kids — often illegally — it was also jailing an exceptionally high percentage of Black children.

From July 2010 to June 2021, children from Rutherford County were booked into the juvenile jail at least 6,350 times, according to the youth commission’s monthly monitoring reports.

In 38% of those cases, the children were Black.

That far eclipses the percentage of children in the county who are Black. That figure stayed between 14% and 16% from 2010 to 2019, according to census data. (Those percentages account for children who identify as Black, whether or not they are of Hispanic ethnicity. The booking data obtained from Tennessee did not indicate how a Black Hispanic child would be recorded.)

The disparity in Rutherford County is comparable to the racial gap for the country as a whole. A fact sheet published this year by The Sentencing Project showed that in 2019, 41% of the children incarcerated nationally were Black, even though Black children make up only 15% of the nation’s youth.

But the newly obtained reports show that the county is an outlier compared to what’s been happening in recent years regarding racial disparities in juvenile justice. In most of the country, the racial disparity has been decreasing. Rutherford County, meanwhile, has gone the opposite direction.

From 2010 through 2017, Black children accounted for 36% of the kids locked up by the county, according to ProPublica’s analysis of the data. From 2018 through mid-2021, they accounted for 58%.

Within Tennessee, Rutherford County stood out for years in terms of the percentage of kids of all races it locked up in cases referred to juvenile court. In 2014, for example, the county jailed children in 48% of those cases. The statewide average was 5%.

Many children in Rutherford County were placed in solitary confinement under conditions a federal judge called inhumane.

After ProPublica and Nashville Public Radio wrote about Rutherford County’s juvenile justice system in October, state lawmakers called the system a “nightmare” and “unchecked barbarism.” The state’s governor called for a judicial review. Eleven members of Congress signed a letter asking the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate the county’s juvenile justice system.

The overwhelming majority of bookings for children of all races occurred from 2010 to 2017, when the annual average exceeded 800. The annual average since 2018 has been just under 100. In 2017, the booking numbers began a dramatic drop after a federal judge ordered the county to stop using its so-called filter system, in which jail staff detained any child considered to be a “TRUE threat,” a vague standard in the jail’s written procedures that wasn’t defined anywhere.

Josh Rovner, a senior advocacy associate who researches juvenile justice issues for The Sentencing Project, found that in 2015, Black youth were five times as likely to be locked up as white youth nationally. In 2019, that figure was 4.4.

“That’s still appalling,” he said, “but it does show progress.” So it’s particularly disheartening, he said, to see places, such as Rutherford County, where the gap is widening.

Sandra Simkins, a Rutgers University law professor and national expert on juvenile justice, served as a monitor in Shelby County, Tennessee, where the DOJ exercised oversight until 2018 based on its findings that the county’s juvenile court discriminated against Black children. In an interview, Simkins said that while many states have taken steps to reduce racial disparities, Tennessee has “blocked every avenue to reform.”

She cited, for example, a finding from our previous story on how Tennessee has stopped publishing an annual statistical report that helped identify outliers on various juvenile justice practices. “No one can get anywhere without data,” she said.

“I think Tennessee tolerates bad actors,” Simkins said. “It is a greater tolerance than what I have ever seen. I have been across the country. I’ve seen a lot of bad pockets.”

Donna Scott Davenport, the only juvenile court judge in Rutherford County’s history, has overseen the juvenile justice system since first winning election in 2000. She did not respond to an interview request for this story and declined to answer questions for our initial story. Davenport appointed and supervises Lynn Duke, the director of the county’s juvenile detention center. “I appreciate your interest in Rutherford County and its youth, but respectfully decline to respond at this time,” Duke replied by email to our most recent interview request.

This year, the county agreed to settle a class-action lawsuit alleging that it had illegally arrested and jailed children for years. At a hearing last week, a federal judge approved a final settlement in which the county will pay approximately $6 million, with hundreds of young people receiving payouts. In response to the controversy, Middle Tennessee State University cut ties with Davenport, who had for years been an adjunct instructor at the school.

Davenport, meanwhile, is up for reelection next year, facing a challenger for the first time in more than 20 years. She has previously said that she intends to run again.