The fight over a quarry in Old Hickory has now zeroed in on a single state permit. The prospective mine operators, Industrial Land Developers LLC, have presented a plan to keep nearby waterways clean while they dig for rock.

But opponents used a public hearing Monday to lob questions at the inspectors who get final say over the permit.

Foes of the limestone quarry have spent months attacking from every possible direction. There’s a lawsuit trying to block the quarry, with concerns ranging from loud blasting to the safety of the nearby Old Hickory Dam, to wear-and-tear on local roads.

But for at least one day, the coalition of neighbors tried to focus on the impacts on water quality, because that’s what the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation has the power to regulate.

Of the roughly 75 people who showed up for the meeting in a conference room at the Comfort Suites hotel in Donelson, several were in disbelief that the quarry has even gotten this close to opening.

The proposal has marched toward approval despite the Metro Council passing a law to limit future quarries and a similar attempt by state lawmakers, which never reached a vote.

Activist Sasha Mullins Lassiter came armed with questions about the science of mining and concerns about what tests may not have been part of the state’s review so far.

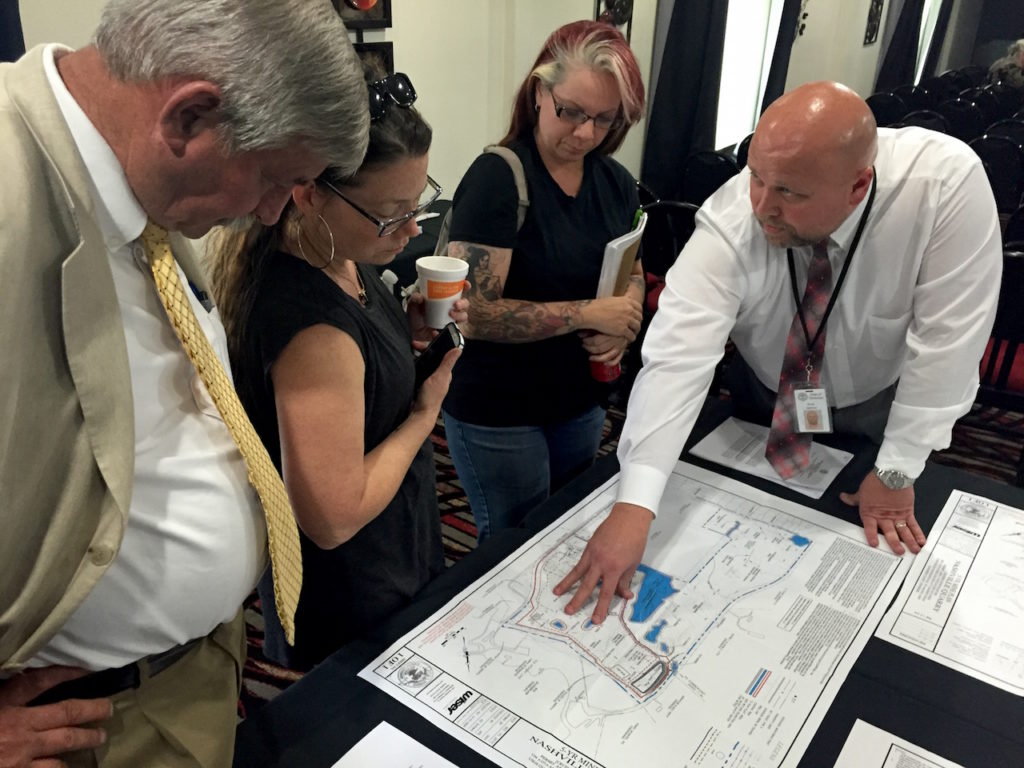

As she looked over a site plan with officials, she asked whether rain from big storms would seep out from the mine’s retention ponds and end up in Old Hickory Lake.

“It’s going to spill everywhere and then it’s going to pollute people’s land, the wetlands. I don’t care how big your berm is here, it’s still going to leak,” she said.

Jonathon Burr, a TDEC deputy director in the Division of Water Resources, answered that such a leak is feasible but unlikely — and that mandating a retention pond that would catch any conceivable downpour isn’t possible.

“Which boils down to the stupidity of everything here,” she replied, before walking off, “thank you!”

She left Burr to take a swig of coffee.

While the exchange set the tone, it wasn’t unexpected.

Burr, who oversees water quality statewide, says he sympathizes.

But his agency only deals with the cleanliness of the water, which must be collected and treated at the mine before going back into local waterways.

“That doesn’t mean that the citizens here don’t have a hundred other concerns about their neighborhood — or about their quality of life, or about their property values; about dust, about noise, about blasting — that are perfectly legitimate things to ask questions about,” Burr said. “We just don’t regulate those here ourselves.”

Public Comments Will Get Formal Response

TDEC will keep taking comments until the last Friday of the month, April 29. Then each call, email, hand-delivered note, and spoken comment from the hearing will get a formal response in the next few weeks.

At the moment, the state’s preliminary finding is to approve the quarry permit, Burr said.

“If we didn’t think that was the case, we would have never put it on public notice in the first place,” he said. “There is a tentative position to approve at this point.”

But, he said, it’s possible for a public comment to send his team back to the “drawing board.”

That could extend the process. But Burr says a few factors are in the quarry’s favor:

The terrain is flat, so the mine pit will collect water easier than an operation on a hillside.

The mine wouldn’t add chemicals into the water, which makes it easy to treat and release.

“Even the stormwater runoff that falls on other parts of the site will still be directed to the [retention] ponds on the site,” he said.

Burr compared the quarry to a sewage plant or a landfill — low on the list of desirable neighbors, but necessary for life to go on.

“Where is all the concrete, all the brick, all the masonry, going to come from for every building that we have? You have to have them. But nobody wants to live next to one,” Burr said. “We’re very sympathetic to people who don’t want this coming to their neighborhood. But all we can do under a permit is look at the water quality implications.”