For years, advocates for victims of domestic violence have been pushing for a relatively small change that would close a big loophole.

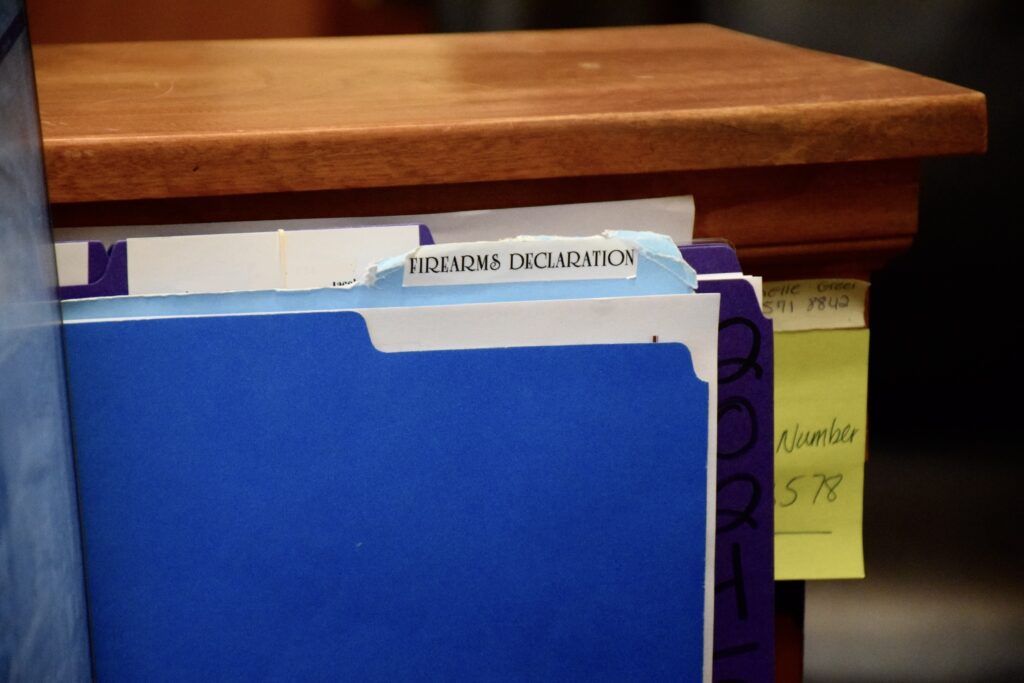

When a court orders an abuser to give up their guns, they can give it to a third party like a friend or a relative. But Tennessee’s form doesn’t have any space to identify who that third party is. That means the justice system can’t be sure who receives the firearm, whether they’re legally allowed to have it, or whether it actually gets to them at all.

This issue has been at the forefront for advocates since the deadly Waffle House shooting in 2018. The shooter traveled across state lines with a gun that he was ordered to give up, but the weapons were returned to him.

The Domestic Violence State Coordinating Council was created by statute to develop policies and practices for law enforcement and the courts on domestic violence. For years, advocates asked the council to add a line to identify the third party to the state’s firearms dispossession affidavit, which is often used in order of protection cases. The council had the opportunity to vote to amend that form at their last quarterly meeting.

But – they didn’t.

“This is something we could do that would help. Just one little thing. And the group that could have done it today did not do it,” says Linda McFadyen-Ketchum, an organizer with the group Moms Demand Action. “And you know it’s not defensible.”

More: Guns in Dangerous Hands

She was in the meeting when the group failed to bring the issue to a vote because of a procedural misunderstanding – a fill-in was running the meeting because the group’s chair was unexpectedly absent.

None of the council members motioned for the issue to be brought to a vote, and so it was pushed to their next quarterly meeting in 2026.

Melanie Bean is the chair of the DVSCC, and wrote in an email statement that the council has dedicated “substantial time” to this issue, and that it is on the agenda for the March meeting. She says that while the DVSCC can vote to amend the form, the only way to ensure that every county in the state changes it would be legislative action. A bill to change the form was brought last session, but did not make it into law after opposition from the NRA.

“I really do think that there was some just procedural confusion,” says Jennifer Escue, executive director of the Tennessee Coalition to End Domestic and Sexual Violence, which helps run the council. “I am confident that we will vote on it at our March meeting.”

She urges county court systems to adopt the change independently in the meantime, as a rural East Tennessee county did.

But McFadyen-Ketchum says the stakes are too high to keep pushing back such reforms.

“How many people are gonna die between now and March?” McFadyen-Ketchum asks.

Investigations by WPLN and ProPublica have found that roughly one in every four domestic violence shootings in Tennessee’s biggest cities were committed by someone who was legally prohibited from having a gun.