Before the Stonewall Riots, before America’s first gay pride parade, Middle Tennessee’s LGBT community was very quiet, but it was there.

For the past seven years, Nashville’s Brooks Fund has collected the stories of what it was to be homosexual in Middle Tennessee before 1970.

They are tales of largely hidden, but vibrant lives.

Linda Compton

Growing up in Old Hickory after WWII, she doesn’t remember hearing the words homosexual or lesbian, not even any gay slurs. Linda Compton didn’t really know what it meant when she found herself drawn to pretty teachers or why boys weren’t as interesting. But her sixth-grade self felt it was wrong when a teenager was forced to ask her church’s entire congregation for forgiveness.

“What did he do, what did he do?” she remembers asking. Her father answered that the teen didn’t date girls, that he was “just one of those sweet boys.”

A few years later, at Church of Christ college David Lipscomb, Compton was so scared of the lesbians rumored to live in her dorm that she hid a butter knife under her pillow for protection. Then she fell in love with a girl. Suddenly, she thought she knew what gay people did. She didn’t feel the need for that knife anymore.

If they’d been caught, Compton says she and her girlfriend would have been expelled and outed to their home churches. So they got boyfriends and went on double dates. The relationship didn’t last; both ended up married to men, but not happily. Compton divorced after five years.

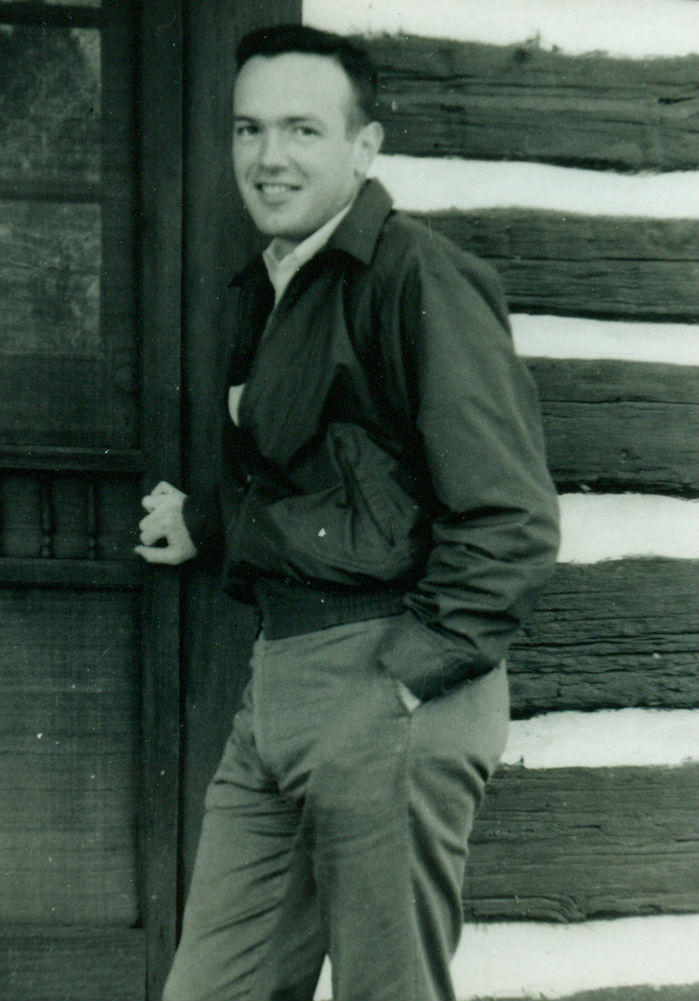

Jere Mitchum

Nashvillian Jere Mitchum dated a girl all through high school and college, but after his dates, he would always head downtown. Certain movie theater balconies and parks were always good for finding men, usually older than himself. Eventually Mitchum told his girlfriend he was homosexual, but she was still determined to marry him.

But, given how many married men on those downtown adventures, Mitchum says he knew he couldn’t find happiness in a straight marriage.

A few years later, Mitchum

settled down with the man who would be his life partner. Al was older, a military officer who served 26 years without being found out as gay.

Ted Binkley

He was never good at hiding his sexuality. The Wilson County native was kicked out of high school for fooling around with another boy. Before long Ted Binkley was leaving home for days or weeks at a time, staying with a trio of hookers at the Maxwell House Hotel. The prostitutes were teenagers, just like him, and they introduced him to men. Looking back, he realizes they must have been pimping him out and keeping the money for themselves.

What Binkley did recognize and appreciate at the time was the protection he got when the police patrolled, looking for signs of gay activity. There was always a little bit of a warning, because many of the bars kept the door locked with a doorbell to request entry. At one bar in particular, the Parachute Club, Binkley remembers the staff would put him in a small room off the back porch before opening the door for officers.

Gay clubs like the Parachute,

Juanita’s and The Jungle became the epicenter of a covert scene, where people could go after long days keeping their guard up in the office or classroom. Linda Compton’s favorite was the

Watch Your Coat and Hat Saloon.

“I never felt freer than I did when I walked into that place,” Compton remembers. “Everybody there was just another me. They even had a drag show, and I thought that was a hoot.”

Gerry Montgomery

He performed in drag shows at the Watch Your Coat and Hat from their start in the late 60s on into the 70s. Gerry Montgomery’s passion was impersonating Diana Ross, but on one memorable night, he played Jane in a pantomime of Ray Steven’s “Gitarzan,” complete with a grass skirt and fake chest made from wig forms. The shows were over the top, fun, and most importantly, liberating for the audiences as well the men who performed in them.

But perhaps the most transformative drag experience happened the 1950s in rural Trousedale County.

Aleshia Brevard

She was then known as “Buddy,” and she was tormented at school for being an effeminate boy. “No one ever called me ‘queer,'” Aleshia

Brevard says, “but I was considered the county’s ‘artist.'” When it came time for a so-called “womanless wedding,” a kind of small-town entertainment in which men dressed as women for laughs, Buddy was encouraged to sing in heels and a gown.

The song was Sophie Tucker’s “Some Of These Days,” a sassy love song with lyrics like “You’ll miss my hugging, you’ll miss my kissing.” During the performance, the superintendent of schools caught Brevard’s eye. Or, more to the point, his head did. It was bald and shining, the perfect canvas for a big, dramatic red lipstick print.

Brevard ran into the aisle and kissed the man on the top of his head. The crowd went wild. “I felt like a canary let out of a cage, and I felt like singing.”

Just a few years later, Brevard was in the cast of a glamorous drag revue at Finnochio’s nightclub in San Francisco — and taking hormones to prepare for one of the nation’s first gender reassignment surgeries. Aleshia Brevard now identifies herself as a heterosexual woman.

The Brooks Fund is continuing to collect the experiences of the Midstate’s

LGBT

community. In additon

to being archived in the Nashville library, the fist twenty-five are part of a documentary that will be released soon.