Updated 6 p.m.

Officer Andrew Delke was booked and released on $25,000 bond Thursday, after a Nashville judge determined there was probable cause that he acted unlawfully when he shot and killed 25-year-old Daniel Hambrick in July.

According to an affidavit filed by prosecutors, Delke chased and shot at Hambrick four times from behind — hitting Hambrick three times — even though the officer could not have been certain Hambrick was the suspect he was looking for that afternoon.

More:

Read the affadavit

.

David Raybin, an attorney representing Delke, said he intends to plead not guilty.

“This is the first time a Nashville police officer has been charged with murder in the performance of official duties,” Raybin said. “When Officer Delke is acquitted, it will be the last time a police officer is on trial for his freedom for just doing his job.”

The shooting of Hambrick has reinvigorated efforts to create a community oversight board that would oversee and review use-of-force cases. The idea is scheduled to go before Nashville voters in November.

The shooting has also led to calls for the resignation of Police Chief Steve Anderson, who released a statement Thursday extending condolences to Hambrick’s mother. Anderson said that Delke had been decomissioned following the charges, as required by protocol.

Anderson had previously ordered a review of the department’s policies governing foot pursuits.

Prosecutors Detail Timeline

Prosecutors on Thursday laid out a timeline of the events that led up to the shooting. It started with Delke being assigned to search for stolen cars in North Nashville on July 26. He later decided to follow a white Chevrolet Impala, which he determined was not stolen, with the goal of initiating a traffic stop.

He did not see the driver or how many people were in the car. That calls into question a claim made by police that Delke had seen the car that Hambrick was in driving erratically earlier in the day.

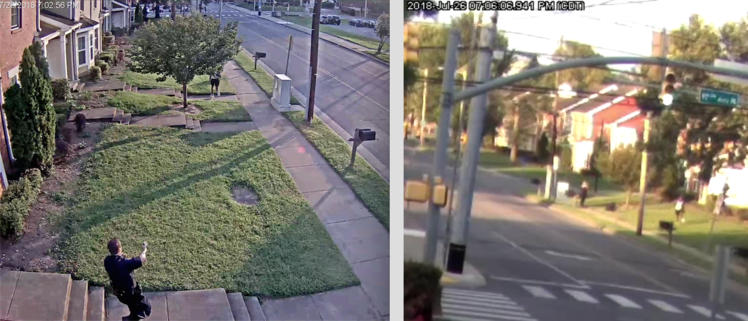

Later, according to the affidavit, Delke approached a white car in the John Henry Hale apartment complex. Hambrick, who had arrived in the area in another white vehicle shortly before, ran away. Delke followed Hambrick on foot and yelled commands for him to stop.

“[Delke] did not know with certainty if the man was connected to the misidentified white sedan, if he was connected to the target Impala, or if he was connected to either vehicle,” the affidavit says.

The affidavit also states Delke saw Hambrick had a gun and yelled for him to drop it. Hambrick did not and continued to run, and Delke “stopped, assumed a firing position, and aimed his service weapon.” He fired four shots; three hit Hambrick.

District Attorney’s Decision

Because Hambrick is black and Delke is white, the case raised questions of racial bias in the Nashville police force. Last year, another African-American man, Jocques Clemmons, was also shot while fleeing.

The white officer in that case, Joshua Lippert, did not face charges. He remains employed with Nashville police, though officials say he has not returned to the beat.

In the Hambrick case, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation was tasked with acquiring the evidence, but the agency said the decision whether to prosecute was left to District Attorney Glenn Funk.

“We investigated this case as we do all others: We gathered relevant evidence, information, and interviews, compiled a detailed set of facts, and presented those facts to the District Attorney General for his further review and consideration,” said TBI spokesman Josh DeVine.

Funk asked a warrant for Delke’s arrest Thursday morning. His request was initially turned down by a Night Court magistrate, only to be granted later by a General Session judge.

Funk says he chose to go to the court, rather than a grand jury, because it would allow the case “to be presented in open court in as transparent a manner as possible, because grand jury proceedings are secret and not open to the public.”

Nashville Mayor David Briley responded to the filing of the charge against Delke is a “necessary step” toward justice for Hambrick.

“I fully support our police,” he said. “However, officers will be required to account for their actions when they have been accused of misconduct.”