Nashville police and the critics of their traffic stops remained at a stark divide after a specially called meeting Monday at Metro Council chambers. Police offered no direct rebuttal to findings that officers disproportionately stop and search the vehicles of black drivers, and the department made no promises of reforms.

Metro police have been confronted by

an in-depth analysis of their traffic stops by the social justice group Gideon’s Army.

The group’s statistician, Vanderbilt University student Peter Vielehr, methodically showed how the group reached its

conclusion: that police may not be intentionally profiling black drivers, but that implicit bias is leading to countywide discrimination.

“Driving while black constitutes a unique series of risks,” he said.

He showed how Nashville police make traffic stops at eight times the national rate.

“Being stopped and searched — having your car and your personal belongings and your person searched when you have done nothing wrong — is victimization,” he said.

The presentation was precise in its explanation of five years’ worth of stop data.

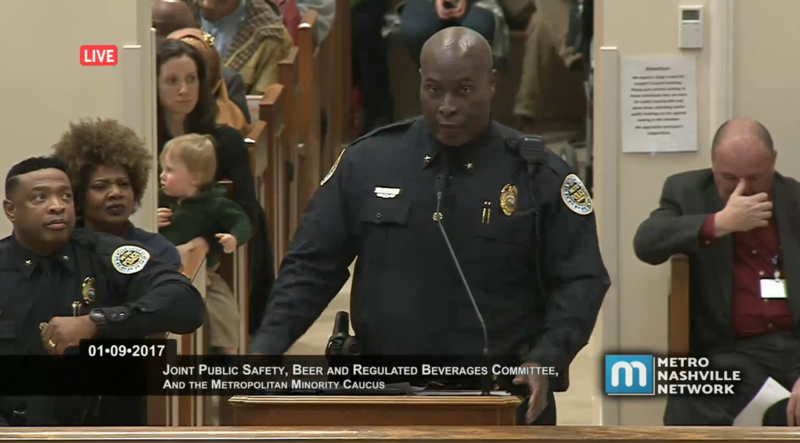

The 10-minute response from police Commander Terrence Graves did not mention traffic stops — opting instead to explain the discretionary powers of police commanders and how all police precincts analyze crime trends and daily statistics to make decisions about policing.

In a talk peppered with tangents and analogies — about running businesses and types of candy — the commander was cut short several times by the moderator.

Under questioning from council members, including Bob Mendes, the commander was drawn back to traffic stop tactics.

Mendes asked about a letter to the council from Police Chief Steve Anderson.

“The chief’s letter to us today implies … that there’s zero implicit bias built into the traffic stops,” Mendes began.

“All people have biases,” Graves interjected. “All people have biases, no doubt.”

The commander also reiterated a police department stance that it deploys its officers to high-crime areas.

That didn’t satisfy Councilman Ed Kindall, who called it “alarming” to see a racial gap in consent searches of vehicles, in which officers request permission to look in a car.

“If a police officer says, ‘Well I’m in this area and I know there’s a lot of crime here, so when I stop somebody, I might ask for a consent search, where I might not ask for a consent search if I stop somebody on West End,’ … to me, that’s the kind of implicit bias that I think people think about,” Kindall said.

Kindall twice asked what the department would do differently in the future. Graves pointed to implicit bias training initiated by the department last year.

“At least we know what is going on, what the perception is, and we’re trying to work on it,” he said.

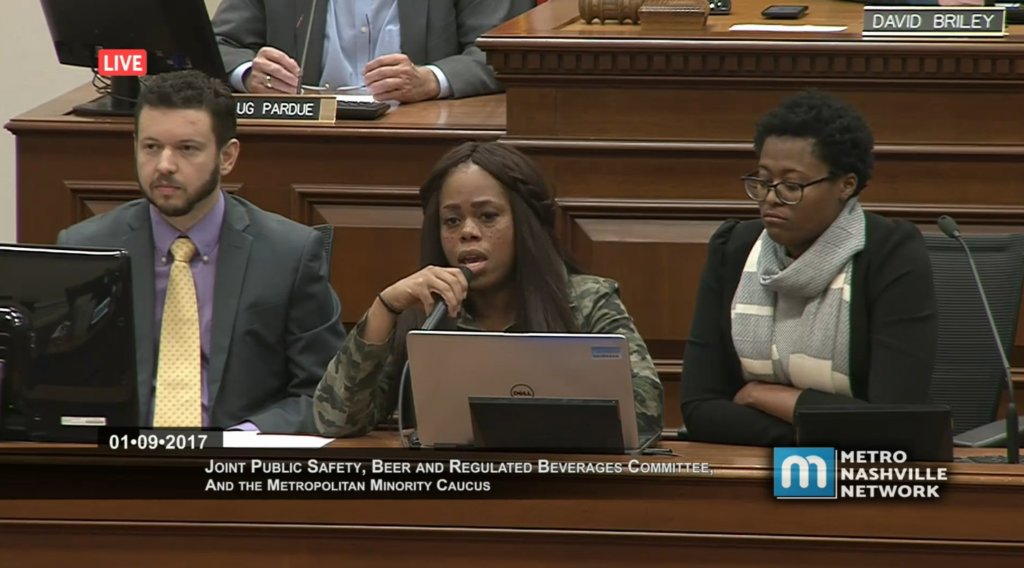

Gideon’s Army fielded few questions. Most pointedly, Councilwoman Tanaka Vercher asked about the demanding tone of the group’s “Driving While Black” report.

Group member Joanie Evans answered that the mission of the study was to uplift community voices and to check whether data supports their anecdotal experiences.

“The language of demands comes from the need to hold institutions of power accountable,” Evans said. “We use strong language because this is an urgent issue that needs to be addressed, when our community members are saying that they are being harassed on a daily basis at a disproportionate rate.”

By meeting’s end, officials were frank about a lingering divide — and again asked police to respond to traffic stop criticisms.

Mendes, meanwhile, wrote on his blog that he plans to bring back legislation to require police to routinely share more traffic stop data.

Police Chief Writes At Length

Councilman Mendes

also posted three documents from the police chief. In those, Anderson offers thoughts about the limitations of data analysis while touting a new department report on crime by ZIP code.

He invites “informed constructive critique,” and says “inflammatory commentary divides the community.”

Anderson goes on to cite the disproportionate number of African-Americans involved in violent crime in Nashville, referring to “a larger social issue.”

“I suggest to you that any disparities in the work of the men and women of the MNPD are a direct result of the challenges we must confront on your behalf each and every day,” the chief wrote.