Tennessee peace activist Hector Black died recently at the age of 95. He was best known for forgiving the man who murdered his daughter and pleading with a judge not to give him the death penalty.

He leaves a legacy of compassion, justice and incredible forgiveness.

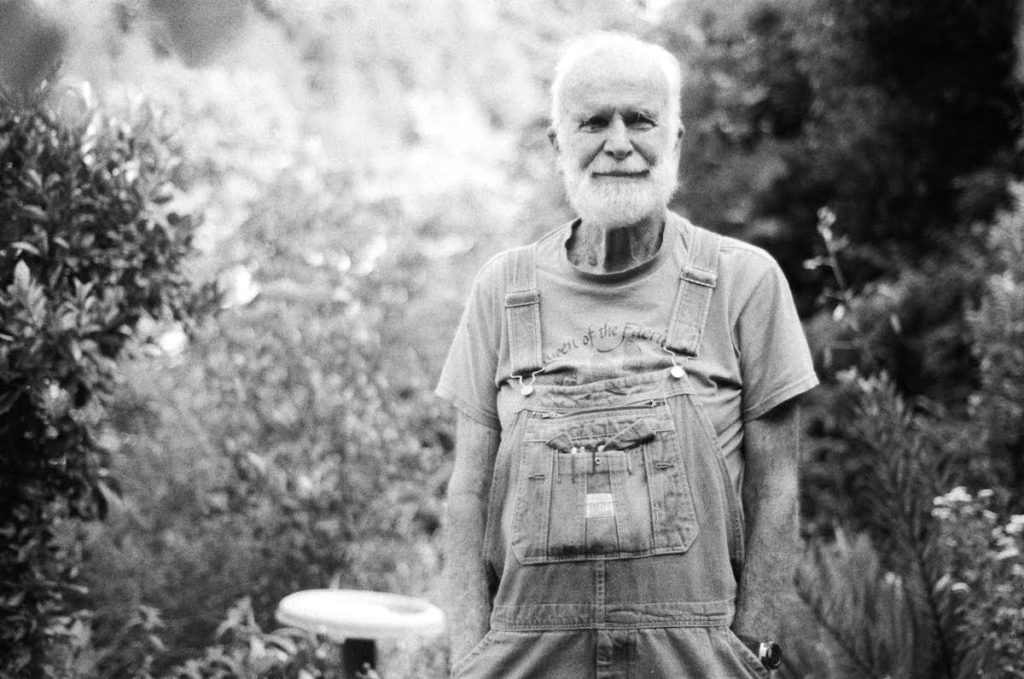

A few years ago he invited me to his farm just north of Cookeville to view the total solar eclipse. There, sporting his regular uniform of bib overalls and blue Crocs, Black recounted chapters of his long, remarkable life.

More: Listen to “How long is the dark?” — an in-depth podcast about Hector Black.

He grew up in Queens, New York. As a young man he served in World War II, where he had a crisis of conscience. “I felt as though I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t kill,” he told me.

A doctor had pity and placed Black in clerk school, attributed to his hammer toes.

It was at Harvard University where Hector started to attend Quaker meetings. He was attracted to their emphasis on peace and nonviolence.

After traveling the world and living in different religious communities, he met his wife Suzie and had three kids. In 1965 they moved to Vine City in Atlanta — the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement. There he organized a rent strike in a slum to protest horrendous living conditions. He was arrested, and Martin Luther King Jr. protested for his release.

“One of the biggest honors of my life was to have him picket to free me from jail,” Black said.

It was also in Atlanta where the family took in two additional daughters. What occurred later is unfortunately what Black is most known for. As an adult one of these daughters, Patricia Nuckles, was raped and murdered by a man high on crack cocaine named Ivan Simpson.

At first, Black said his devotion to nonviolence faltered.

“I yelled out ‘I’ll kill the bastard,’ and all my nonviolence went out the window.”

But he had a change of heart.

“I said in the courtroom, you know, that ‘I don’t hate you Ivan Simpson, but I hate with all my soul what you did to my daughter,’ ” Black recalled. “I wish for all of us that have been so wounded by this crime that we might find God’s peace, and I wish that also for you Ivan Simpson.”

When Black looked Simpson in the eyes for the first time, “it was like a soul in hell. I’ve never had a look like that before in my life.”

Black later read a letter that pleaded with the judge not to give Simpson the death penalty, saying that “only love can overcome hatred and violence.”

Black and Simpson went on to write letters to each other and developed a sort of friendship.

Black told me that Simpson wrote him a particularly kind note when his wife Suzie died.

I could see where she was interred on the property.

Meanwhile, in the sky above Black’s organic plant nursery, the moon was just beginning to cover the sun. Nestled in a valley surrounded by waterfalls, Black and I were about to witness a miracle together.

“I’m waiting,” Black said. “The birds are still singing. I’m waiting to see what happens when it gets dark.”

Then, “Oh!” he half gasped, half laughed. I could see that he was filled with awe and wonder at age 93.

It is without a doubt that he has left a lasting impression on so many people. He was hospitable to the core, generous and truly down to earth as he fought for peace.

Even just a short while ago, Hector was at a Black Lives Matter rally with a walker and a mask. As one friend said, “he fought with love until his dying breath.”

As Black and I watched the sunlight return, it revealed some of his massive dawn redwood trees. Underneath them Hector’s daughter Patricia and his wife Suzie were buried. Now, Black rests alongside them.

Alexis Marshall produced the web version of this story.