The number of Tennesseans who can’t vote because of a felony conviction has risen since 2016 — despite a national trend in the opposite direction — according to a new national report released today.

The report from the Sentencing Project says that about 5.2 million Americans are barred from the polls because of a criminal record, including more than 456,000 here in Tennessee. The state has some of the strictest rules in the country for people who want to restore their voting rights after they’re convicted of a felony.

Researcher Christopher Uggen, who co-authored the report, says restrictive state laws and low voter registration go hand in hand, especially for minority residents.

“I’ve been following these legal changes for a couple decades now, and I was really excited to work on this report this summer and hopeful, based on all these legal changes,” he says. “It’s utterly disappointing and frustrating that we head into this election with that level of dilution of voting power, particularly in communities of color.”

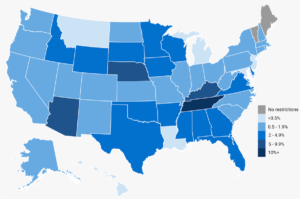

Courtesy Sentencing Project

Courtesy Sentencing Project A heat map in a new report from the Sentencing Project shows that Latino residents with a felony conviction are disenfranchised in Tennessee at a higher rate than in any other state in the U.S.

The data is most striking for Latino residents. Tennessee has the highest rate of disenfranchised Latino voters of any state, at more than 10%.

The state ranks second for the overall percentage of voting age residents who can’t vote due to a felony conviction, as well as for the percentage of Black voters banned from the polls.

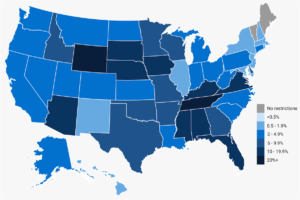

Black people are even more greatly impacted than others with a felony on their record. About one in 11 Tennesseans with a felony conviction can’t vote. The number is about one in five for Black residents.

“It should come as no surprise that a society that aggressively polices and incarcerates Black Americans at rates far greater than the rest of the population also disenfranchises Black Americans at far greater rates,” says Sakira Cook, an advocate for criminal justice reform with the Washington D.C.-based Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Those disparities were clear four years ago, when the Sentencing Project put out its last report on felony disenfranchisement. Since then, the impact on Black Tennesseans has actually increased slightly.

The overall number of disenfranchised residents in the state has increased, as well.

In the past four years, an additional 35,000 Tennesseans with felony convictions have lost the right to vote. Meanwhile, just 3,415 have restored their right to vote.

Courtesy Sentencing Project

Courtesy Sentencing Project More than one in five Black Tennesseans cannot vote because they have been convicted of a felony.

Other states have struck down restrictions to make it easier for people with criminal histories to vote, and they’ve helped hundreds of thousands of people get their voting rights back.

Kentucky, the Sentencing Project reports, has restored voting rights to 181,361 residents since 2016. In Virginia, the number was even higher: 195,371. The governors of both states signed executive orders that made all people who complete their sentences eligible for restoration.

In Tennessee, on the other hand, formerly incarcerated individuals must pay off all court debts, including child support payments, before they can vote. No other state requires potential voters to be up to date on child support, and only a few bar people with outstanding court debts.

Uggen says the best way to make lasting change is through legislation. A bill that would expand voting rights for those with felony convictions and eliminate the financial barriers was introduced in the Tennessee legislature earlier this year and received bipartisan support. But it was sidelined by COVID-19.

In the meantime, the Nashville-based nonprofit Free Hearts has created the Fines and Fees Fund to help those who can’t afford to pay off their court debt. The organization also helps Tennesseans navigate the maze of paperwork, meeting and phone calls required to secure a certificate of restoration.

“No one should lose their voting rights,” says Dawn Harrington, the executive director of Free Hearts. She restored her voting rights this summer and voted for the first time in the August primary after struggling for more than a decade to get her rights back.

“Whether you have money or not should never keep us away from being able to vote,” Harrington says. “It is not a crime to be poor.”

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member.