Clara Schumann was in her mid-30s when she lost her husband, first to mental illness and then to an early death. While it was a tragic end to a compelling love story, it was also the beginning of a new phase in Clara’s work as a pianist.

J Hoeflich / Wikimedia Commons

J Hoeflich / Wikimedia Commons Robert and Clara Schumann

During Robert Schumann’s final two years, between bouts of what was then known as “melancholia,” he had composed quite a bit. Clara became a champion of these works, along with Robert’s entire catalog after his death. She even edited his complete works, which were generally unknown in his lifetime. Her performances, alongside a few performances by Franz Liszt, kept Robert’s music in the public eye. To put it plainly: Clara Schumann is responsible for the respect and reverence that Robert Schumann’s music boasts today.

War of the Romantics

While Liszt occasionally performed Robert’s music, and had nice things to say about Clara’s playing, Clara did not seem able to return the favor. In the War of the Romantics, the deep philosophical split between German musicians was whether music should stand in the abstract, or paint a specific picture. Liszt went so far as trying to set up a club of composers around the newer, ostensibly more progressive idea of “programmatic,” or descriptive composing. Johannes Brahms is often labeled the standard bearer of the conservative “absolute” music side, with his first symphony being teased by critics as “Beethoven’s Tenth.” But it was Clara Schumann who consistently wrote scathingly of the more progressive Liszt and Wagner.

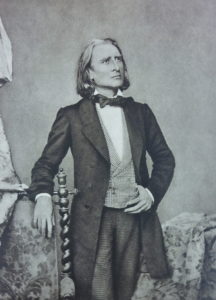

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons pianist Franz Liszt

She described Franz Liszt as a “spoiled child.” Not one to mince words, she also said, “Before Liszt, people used to play; after Liszt, they pounded or whispered. He has the decline of the piano on his conscience.” And upon seeing Liszt’s effect on other women in the audience, including fainting spells, fighting over locks of his hair, and actually attempting to tear his clothes off, she made just a quick observation: “It was revolting.”

Before the mid Romantic period, concerts were a mixture of types of performances rather than one coherent recital. While it was Liszt who gave the first solo recital of just piano music, his opera aria arrangements and tendency toward showmanship often lasted as long as four hours. It was Clara Schumann, who could easily be labeled his rival, who did shorter programs, taking a chance on music that had been considered too heavy or deep for the concert hall. It is Clara’s model that we still use today.

In 1857 Clara Schumann moved to Berlin and continued concertizing. Her touring schedule seems punishing for a single person, let alone a widow with seven living children. She made 20 trips to London and even toured to Russia before settling down with a teaching position in Frankfurt at the Hoch Conservatory. She played the most difficult works of Bach, Beethoven and Scarlatti, alongside music of her beloved Robert, as well as contemporaries and friends Felix Mendelssohn and Johannes Brahms.

Clara and Johannes

Only four months after the Schumanns had met their friend Brahms, Robert Schumann attempted to drown himself in the Rhine River. Clara continued to correspond with the younger composer, and he became a devoted friend. The passion with which the two wrote to each other is the source of a great deal of speculation about the nature of their relationship. Even early in their friendship Brahms wrote, “I would gladly write to you only by means of music, but I have things to say to you to-day which music could not express.” And after Robert’s death he switched from addressing her as “Honored Lady” to “Beloved Clara.”

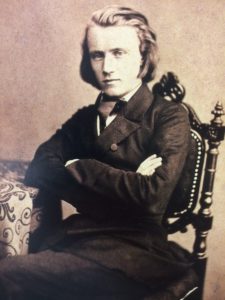

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons young Johannes Brahms

The admiration was not one-sided. Clara had a new confidant in whom to share her artistic insecurities. “You cannot imagine how sad I am when I feel I have not put my heart into my playing.” She wrote. “To me it is as if I had done an injury not only to myself but also to art.” And she eventually opened up more sentimentally, “I am waiting for another letter, my Johannes. If only I could find longing as sweet as you do. It only gives me pain and fills my heart with unspeakable woe.”

After Robert’s death Clara and Brahms vacationed in Switzerland, seemingly with the intention of getting married. But, upon their return, Clara left Brahms at the train station, and told her daughter, “I feel as if I just left a funeral.” Clara never remarried. Johannes Brahms never married. But the two remained close.

Clara Schumann was the first to publicly perform any work by Johannes Brahms after their meeting. He sent her every manuscript, looking for advice. Apocryphally, he wrote his left-hand arrangement of JS Bach’s D minor Chaccone because Clara had injured her right hand. The original solo piano version of his Variations on a Theme by Haydn was the last piece Clara Schumann performed in concert.

Johannes Brahms wrote one of his last songs, “Vier ernste Gesange,” while Clara was on her death bed. He sent a copy to eldest daughter Marie Schumann with a note that called them, “a true memorial to your beloved mother.” Clara died in 1896, and Johannes Brahms followed just eleven months later. A few years earlier it had been Marie who stopped Clara from burning her letters from Brahms.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons Clara Schumann

Students of Clara Schumann taught at the Royal College of Music, and at the newly formed Juilliard School. When the next generation of virtuosi entered the concert hall (Von Bülow and Rubinstein) it was Clara’s model of programming that they followed. And now as her 200th birthday approaches, a new generation of pianists, orchestral musicians, singers and composers has a renewed opportunity to look at the legacy that helped shape the concert hall today.

This is Part 2 of the story of Clara Schumann. Part 1 can be found here. 91Classical is celebrating the composer and pianist Clara Schumann with a two-week festival around her 200th birthday.

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))