A warning to readers that this story discusses sexual assault.

Sibling sexual abuse can happen in any family, regardless of socioeconomic, racial or religious background, and has become so frequent that experts call it a “silent epidemic,” with incidents rising in Tennessee.

Today, about one in 10 kids that forensic social worker Lisa Milam sees has been sexually abused by another child in the same home. That could mean everything from foster siblings to cousins growing up together, though in her experience, offenders are most often a biological or step-sibling.

Milam works with the Nashville nonprofit Our Kids, which offers forensic exams and crisis counseling to survivors of child sexual abuse from roughly half the state.

She does not want to minimize any abuse but says that, by far, “the most painful moments in my office are with parents who have one child that is the alleged offender, and another child who is the alleged victim.”

It’s hard enough to remove an abusive adult from a child victim. But when it’s a sibling, there is even greater emotional, physical and financial strain because the first step is to separate the children.

“It’s paralyzing,” says Milam. “There are some situations where you have one parent who may be forced to move out of the home with a child. And how many people can really do that?”

Because of the difficulties, parents might be slower to acknowledge sibling sexual abuse, and may also not report it. This can happen out of fear of child protective services or even the courts, which can treat kids like adult offenders, penalize families of color and even delay family therapy.

So what has caused the uptick?

Milam says kids’ unprecedented access to sexualized content, especially on smartphones.

“There’s no longer this idea of, ‘I wonder if my child is doing this?’” says Milam. “I assure you, your child is being exposed to it, they’re looking at it, they’re receiving it, and they’re taking pictures of themselves.”

Knoxville-based therapist Brad Watts says pornography is a significant factor in the cases he sees.

“I have not treated a single individual over the last six, seven years that has committed sexual harm … without having a problem with pornography,” Watts says. “A serious problem.”

He says growing research shows exposure to violent porn makes kids much more likely to be sexually aggressive.

Now, Watts says, not all kids who look at porn become sexually aggressive. Nor is all sexual curiosity among siblings a red flag, especially if it’s out in the open and the kids are close in age. However, like adult offenders, children also count on secrecy and shame, so it is concerning when there are large differences in age, size or emotional maturity.

“With sibling sexual abuse, there tends to be more manipulation, coercion, and you really want to look at that power differential,” says Watts.

Addressing sibling abuse

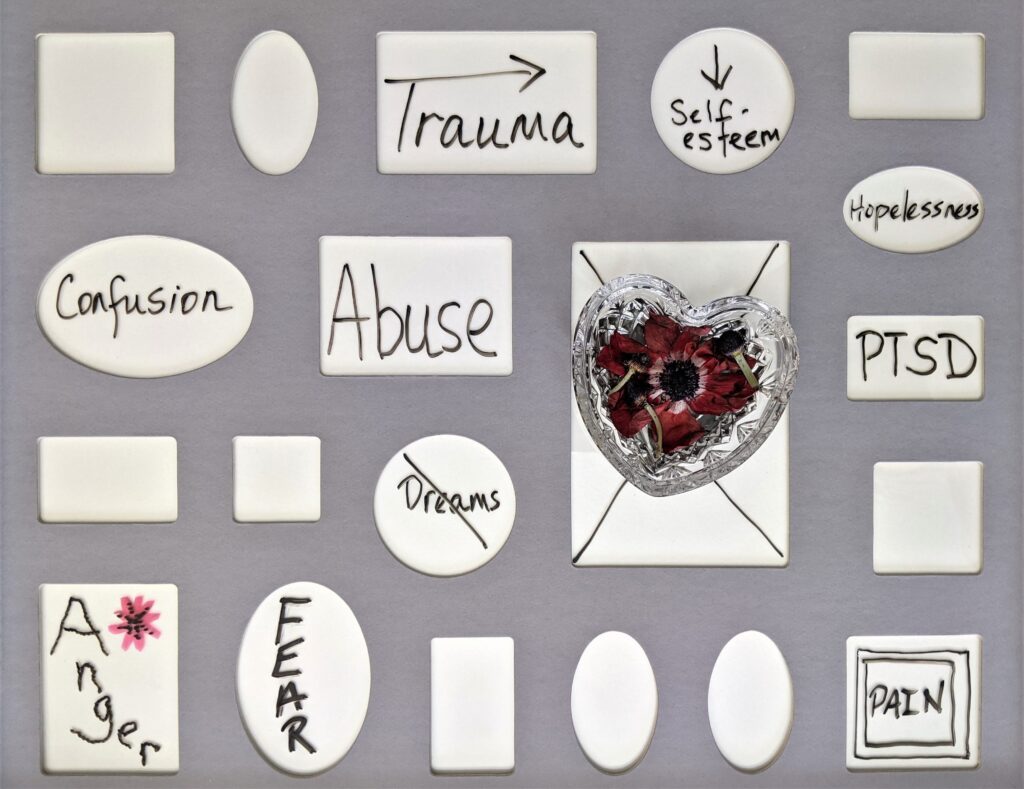

Watts authored one of the few books on the subject, “Sibling Sexual Abuse: A Guide for Confronting America’s Silent Epidemic,” in part he says, to help children and adults come forward and heal without guilt or shame.

He also wants the book to be an educational tool for other therapists working with families. That’s because, despite the rise in incidents, there is still very little research, training or even standardized response.

“Honestly, law, social services and professionals don’t know what to do,” says Watts.

As painful as it is, Watts says it can be treated — with services and therapy for child victims and offenders, and ultimately the entire family.

Milam says it’s important for parents not to blame themselves, and that families need to know that “it’s not the end of the world, and that the majority of kids who act out sexually on a sibling do not grow up to be adult sex offenders. They just don’t.”

She often tells parents that they are not alone: “Nobody talks about it, but when you go to your child’s school or to church or to Walmart, there are families all around you that are also dealing with this. And that shame you feel, ‘You’re the only one,’ or ‘What’s wrong with you?’ — you can let go of that too.”

As for prevention, both Milam and Watts suggest:

- Filter kids’ device settings and limiting access, especially at night

- Have age-appropriate conversations about sexuality — and pornography

- Above all, make kids feel safe to come forward

Apart from the shame, children are terrified of breaking up their family, or thinking that they won’t be believed or supported.

“The real key,” Watts says, “is knowing that parents will believe them and take action.”

Experts say they’d like it to be as easy for kids to speak up about sexual assault as it is for them to tell on a sibling who’s hit them or stolen a toy.

Clarification: This story originally included a quote from therapist Brad Watts that could have been misconstrued. A different quote has been substituted.