A Tennessee law that criminalizes housing immigrants without legal status could apply even if the person being housed has citizenship.

Enforcement of the law relies on Immigration and Customs Enforcement making a “determination” about the person’s status. Attorneys challenging the law argued in federal court Wednesday that ICE does not make final or official decisions on a person’s immigration status; that’s for an immigration court to decide.

State attorney Miranda Jones said that, under the law, an arrest warrant or a notice of appearance from ICE counts as a determination, even if its investigation finds that the person was lawfully in the United States.

“If ICE has said you are not here legally, even if that turns out to not be true, it’s still sufficient (to prosecute),” Jones said.

“What if ICE is wrong in their determination?” Judge William Campbell asked.

“Yes, they would be culpable,” Jones said.

She told the court that she had concerns with the law when she was first assigned the case, but that she now sees the similarities between Tennessee’s law and federal anti-harboring laws. For those cases, guilt is not determined by whether a fugitive is ultimately found to be innocent, but whether the person harboring them knew that they were harboring a fugitive at the time.

The state argued the law only applies to human smugglers who house people without legal status for financial gain.

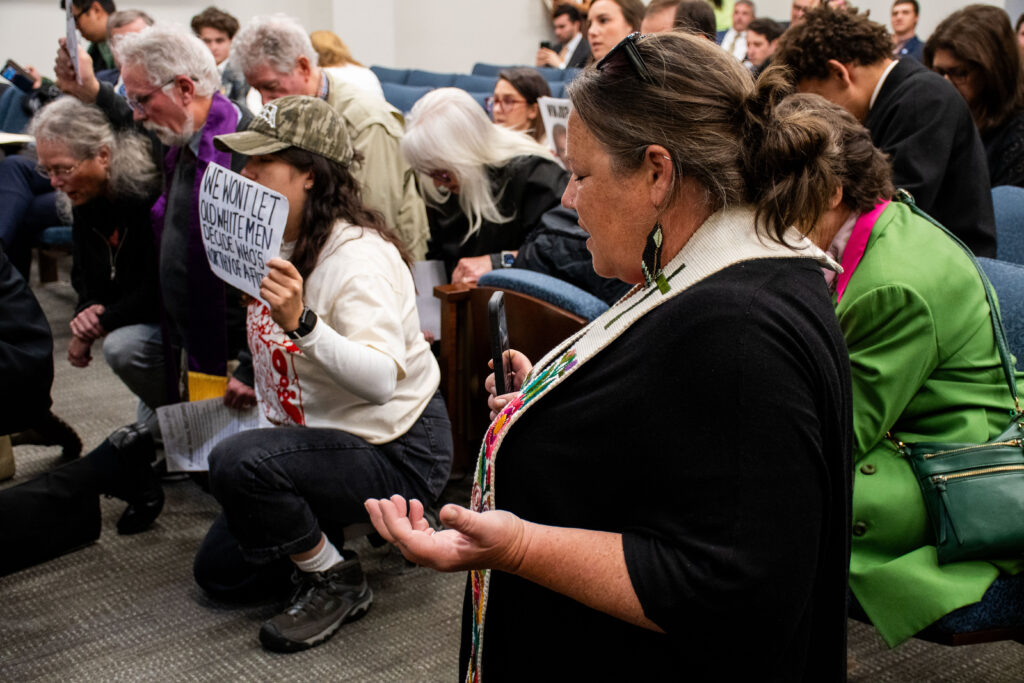

Still, the churches and landlords who brought the lawsuit are concerned they could be criminally charged for offering aid or renting a home to someone without legal status.

Attorneys representing the plaintiffs told the court that the law has already had a chilling effect on landlords, who have preemptively evicted tenants out of fear of prosecution. The Southeastern Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, too, fears it could be swept up in the law, because it accepts donations and rents out spaces for weddings.

Attorney William Powell asked the judge to temporarily block the law from being enforced, arguing that its language is too broad.

“I don’t think (the General Assembly) intended to pass a bill with this scope,” Powell said.

Jones said the wording could’ve been clearer, but the law is still constitutional.

“It’s not whether (the General Assembly) made the best choice, it’s whether they made a permissible choice, which they did,” Jones argued.

Judge Campbell initially asked both sides to agree on how enforcement should be handled while the plaintiffs await trial. After a 30-minute recess, the state said it could not accept the plaintiff’s ask that their clients be safe from prosecution under the law while the case moves forward. Jones said that the state did not want an injunction because it would “tell people that the plaintiffs are likely to succeed.”

However, Judge Campbell indicated he may order the state to give the court notice before arresting or charging any of the plaintiffs named in the case, or else release a partial injunction that protects those involved in the suit.

Church leaders and immigrant activists are awaiting the temporary ruling. Nashville Rev. Ingrid McIntyre, who opposed the law when it was first proposed in the statehouse, said that the measure limits the church’s good works.

“This law criminalizes the very acts of hospitality and sanctuary that Jesus commands us to practice,” McIntyre said. “When the state makes it illegal to house the homeless immigrant, to welcome the stranger, to provide refuge for the refugee, it forces us to choose between Caesar’s law and Christ’s law.”