Wind power accounts for nearly half of all renewable energy in the U.S., and virtually all of it comes from outside the Southeast. It doesn’t have to, though.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, for example, has 0.025 gigawatts of wind in Tennessee. That is less than what’s needed to power Vanderbilt University, and the federal utility does not currently have plans for any additional wind development.

Tennessee could, however, make wind its dominant source of power, according to data analysis by the National Renewable Energy Lab, or NREL.

“If communities and wind developers were to follow best management practices, Tennessee would have 73 gigawatts of potential,” said Anthony Lopez, a senior researcher at NREL who leads their research on renewable potential in the U.S.

Technically, Tennessee could have 235 GW of wind power with current technology, if only considering physical constraints like wetlands or buildings. Under the strictest scenario, considering possible stringent citing ordinances, Tennessee has about 13 GW of wind energy potential, which still equates to more than a third of TVA’s entire, nearly 34-GW energy mix of nuclear, fossil fuels and renewables.

‘You can basically fine-tune these machines’

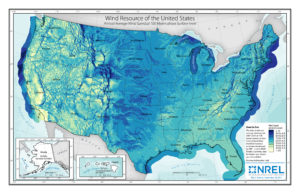

To determine wind energy potential, NREL considers wind speed, how well turbines can harness that wind in relation to factors like electrical losses and how often the wind is blowing — in addition land availability.

“You take all of three of those, combine them together, and you get potential,” Lopez said.

Courtesy National Renewable Energy Lab

Courtesy National Renewable Energy Lab Tennessee could transform a huge portion of its energy supply to wind power in the coming decades.

In 2012, Tennessee was estimated to have less than 1 gigawatt of wind energy potential. But NREL refined their analysis and updated figures based on the latest technology and understanding of energy economics — today, wind turbines are cheap, ubiquitous and expected to get cheaper.

“Turbine technology has advanced so considerably,” Lopez said. “It can be deployed at high wind speeds and low wind speeds. You can basically fine-tune these machines to go at any wind regime.”

Wind projects built last year have public health benefits, climate benefits and grid value worth more than triple the cost of generating electricity from wind energy, according to research from the Lawrence Berkely National Laboratory.

Misinformation can derail wind projects

NREL says the single greatest challenge that remains to widespread wind deployment is local siting ordinances, which can be influenced by misinformation campaigns linked to the fossil fuel industry.

Bad or outdated information has even been shared by local news media. An article published by The Tennessean in October stated that Tennessee was “wind-poor,” an idea now debunked.

In addition to local pushback, wind development in Tennessee could face challenges due to statewide ordinances: Tennessee has a minimum setback from any non-participating landowner’s property line equal to 3.5 times the total height of the wind turbine. The state also set a noise limit of 35 decibels for residences during the 2018 legislative session.

“That’s on the more restrictive side,” Lopez said.

California, for instance, has a property line setback of 1 times the maximum height of the turbine and a sound limit of 60 decibels. Most states don’t have statewide regulations on wind turbines, but many cities and counties have ordinances, particularly in the Great Plains and Midwest, that can effectively block projects.

Another common barrier to wind development is the perceived aesthetics, because wind farms do sprawl large chunks of land — even if they don’t take up much space.

U.S. wind farms currently extend across the equivalent size of New Hampshire and Vermont combined. Only a tiny fraction of that area, between less than 1% to 4%, is estimated to be directly impacted or permanently occupied by physical wind energy infrastructure, so most land is available for other uses.

Wind farms are usually developed on land already used for other forms of human activity, with rangeland and cropland having supported about 93% of wind deployment. Agricultural land accounts for about 52% of the U.S. land base, and most of it is used to feed cows, according to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Although wind power is considered “low impact” on the surrounding landscape, NREL recently suggested that new research is needed to understand potential ecological disturbances from a quickly expanding wind energy portfolio across the U.S.