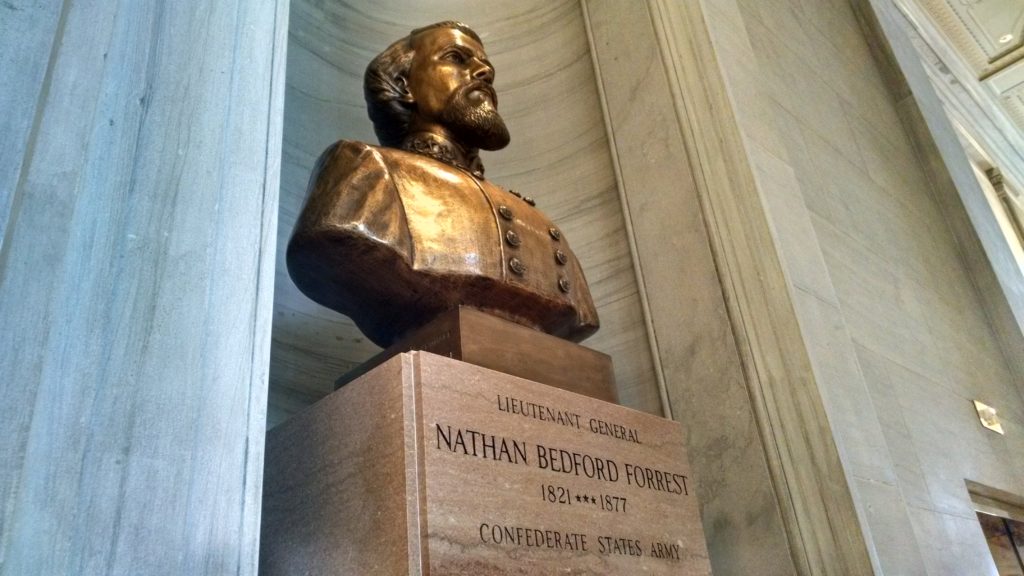

After decades of protests, the Tennessee Historical Commission voted Tuesday to relocate a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest from the state capitol.

The bust is one of three that will be moved to the Tennessee State Museum. The others depict U.S. Admiral David Farragut, a famed commander in the Union Navy during the Civil War, and U.S. Admiral Albert Gleaves, who served more than four decades.

More than 30 citizens spoke during the public comment period in the hearing Tuesday. Many of them advocated for removal of the Forrest bust, in large part because of the message it sends to Black Tennesseans. Forrest was involved in the slave trade, a massacre of many Black soldiers at Fort Pillow during the Civil War, and the Ku Klux Klan.

“Given the array of obstacles employed in blocking the removal of this statue, what do we truly value and protect as a society?” activist Angel Stansberry of the People’s Plaza asked. “How I wish that Black bodies were shown half the reverence afforded to this unfeeling bust of stone.”

Gov. Bill Lee and Sen. Brenda Gilmore, D-Nashville, joined in the call to relocate the statue.

“There’s a reason this particular bust has for 40 years stood above others as controversial,” Lee said in a video statement. “It’s because this individual, during a season of his life, significantly contributed to one of the most regretful and painful chapters in our nation’s history.”

H. Edward Phillips represented descendent of Nathan Bedford Forrest, and was one of few speakers who opposed the bust’s relocation. Phillips also represents a chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

“What I’d like to remind everybody is that this is not about feeling, this is actually about the law and what the law requires,” says Phillips. “Is there historical reason to move this monument, this bust? Is there a great public reason to do this? I certainly understand the public comments. I understand the public outcry. However, I don’t think there is a sufficient historical rationale to remove this.”

Forrest’s bust was approved by the legislature in 1973, in the years following the Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

More steps ahead in removal process

According to the state’s Heritage Protection Act, the commission has 30 days to post its final ruling online. Groups unhappy with the ruling have two months from then to file a petition for a review in court.

Even if a court does not intervene, officials must wait four months after the ruling is posted before the monuments can be relocated. At the earliest, that could not happen until late July or August.

Tennessee is one of several Southern states, along with Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina and South Carolina, that have passed preservation laws that make it challenging for monuments to be removed or relocated. The laws can make the process arduous and lengthy.

In total, Tennessee is home to more than 100 Confederate symbols, according the the Southern Poverty Law Center, including about 47 monuments, more than 40 highways or roads and several parks.