Tennessee health leaders shared new details Sunday about how hospitals are scrambling to handle the state’s crush of COVID-19 cases. And Gov. Bill Lee prepared to make a rare statewide address at 7 p.m.

Hospital leaders say they’ve had to improvise, as nearly 3,000 people are hospitalized and treatment is underway for far more patients than ever thought possible.

They say they are trying to bend but not break as they wait for vaccines.

“If we have another surge after Christmas and New Year’s like we did after Thanksgiving, it will completely break our hospitals,” Tennessee Health Commissioner Dr. Lisa Piercey said Sunday.

Among new details from Tennessee hospitals:

- Two rural hospitals have requested ventilators from Tennessee’s emergency stockpile.

- The state has received a federal emergency team to help in northeast Tennessee.

- The health department has identified 600 people who could take temporary jobs through the medical reserve corps.

- Higher education officials have identified nearly 100 health care workers who returned to school to take shifts during holiday break.

- Alternative care sites in Memphis and Nashville have been rendered useless because there’s no contract staff available to run them.

From outside the walls, most people could never tell how serious the situation is. Visitors are largely kept out. Patients aren’t spilling into the street. Ambulances don’t line up around the block.

But inside, hospitals are constructing new COVID units.

Urgent alterations

In an effort to avoid treating patients in hallways, emergency departments are doing flash renovations. Last week, Dr. Duane Harrison’s ER at TriStar Hendersonville turned the waiting room into a patient care area. A small cafe is now the waiting room.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsDr. Duane Harrison is the medical director of the TriStar Hendersonville Medical Center emergency department, which recently converted its lobby into a patient care area.

“We’re already taking measures for the onslaught that we believe is coming,” Harrison says. “It is daunting to walk into the emergency room at 6 a.m. and see 13 people and know that there are no beds upstairs and know that you are waiting for discharges and, unfortunately, deaths. But we keep making a place.”

Harrison says it’s not going to be comfortable, but it’s better than the alternative of turning people away.

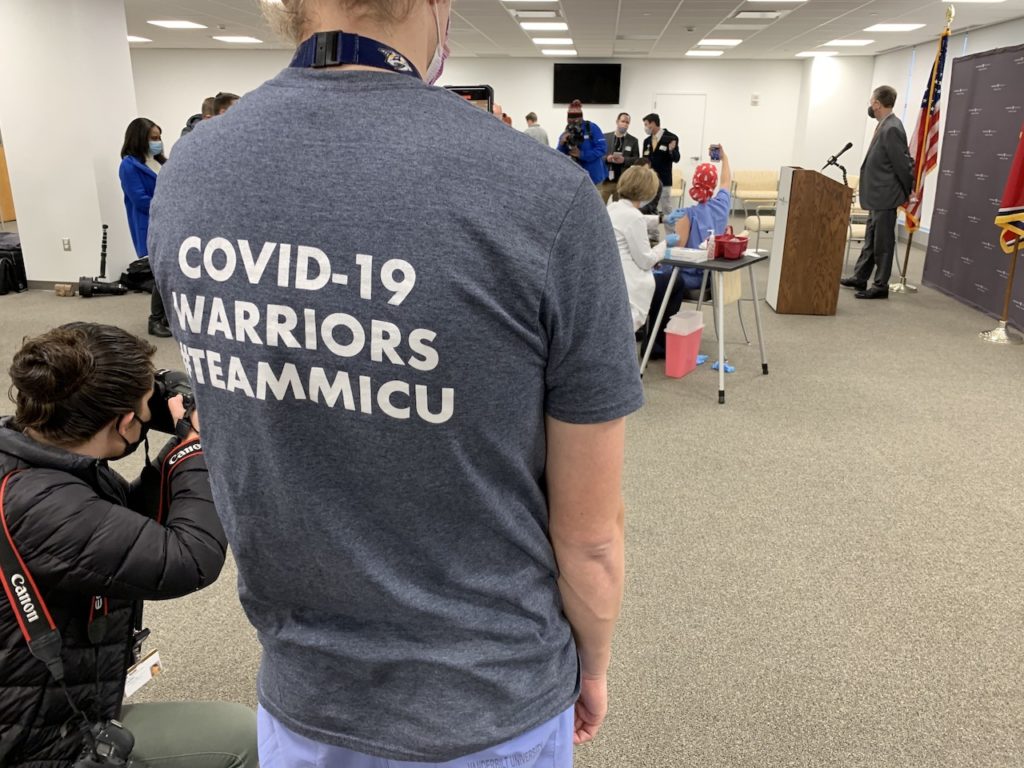

Even Vanderbilt University Medical Center — with its giant staff, massive campus and top infectious disease capabilities — drew a line earlier this year.

“You know, we thought we knew where our breaking point was,” says chief nursing officer Robin Steaban.

VUMC crossed that threshold several weeks ago.

“There is a breaking point. We have not discovered that yet, but we know that there is one when it’s going to be impossible to do the kind of care we want to do for patients,” she says.

That’s not to say coping has been pretty.

Dr. Todd Rice has been fielding calls from as far away as Missouri and Virginia from hospitals with no room or no capabilities for complex COVID patients. Rice directs Vanderbilt’s COVID ICU and has to tell other physicians there’s no room at VUMC either, at least not for their transfer patients.

And turning anyone away feels wrong for a major medical center that’s thought of as a backstop for the region, he says.

“We want to help them,” Rice says. “And here we’re having to really triage our resources and say this person is a person who is sicker and I can help. And I’m going to have to hold on you for right now.”

So a strange thing is happening. Even smaller hospitals that would usually refer critical cases to urban medical centers can’t do that and are actually having to accept overflow from out of state.

“It’s pretty unusual for us — or was unusual — to get patients [from out of state]. Now we’re getting them fairly regularly,” says Dr. Matt King, a pulmonary critical care physician at Sumner Regional Medical Center in Gallatin.

He had one patient flown in the other day from Kentucky who had looked for a bed from Ohio to Alabama. And this wasn’t even a COVID patient.

But COVID is what’s causing the capacity issues. King says patients are hospitalized for weeks.

submitted

submitted Dr. Matt King has been caring for COVID-19 patients at Sumner Regional Medical Center since they began showing up in March.

“It doesn’t take very many patients staying for a week or two weeks for us to fill up,” he says “The hospital really relies on being able to get people in, get them well, and get them home quickly so we can take care of the next person.”

Uncommon measures

Doctors say they are doing things that feel risky. Like sending patients home earlier than they typically would, even when they still need oxygen.

“Actually right now, I’m signing some paperwork to get a patient home with oxygen,” he said during an interview last week.

Hospitals are also telling more people who show up for care to come back only if things get worse.

“You’ve gotta meet some pretty strict criteria to be admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 right now,” says Dr. James Parnell, president of Tennessee’s chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine.

Hospitals will have to make even more space, because they know additional cases are coming on account of the massive surge in new cases and for all the holiday gatherings that will go on despite the increasingly desperate pleas of public officials.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified Dr. Todd Rice.