The Nature Conservancy recently struck a deal with the state of Tennessee to permanently protect about 43,000 acres in the central Appalachian Mountains.

The area contains hardwood forests that house migratory songbirds, a small population of reintroduced elk and about 180 miles of streams in East Tennessee at the Kentucky border.

To help safeguard this wildlife habitat, the Nature Conservancy sold the state a conservation easement, which is a legal agreement that restricts development in exchange for tax deductions.

The agency’s Cumberland Forest Project has a private investment capital fund that will continue to own the land. But even if the land is sold, the easement will be permanently enforced by the state, according to Gabby Lynch, the director of protection at the Nature Conservancy.

“Forty-three thousand acres is a huge area that now is protected forever for wildlife and for people,” said Lynch, who explained that it’s part of a larger area that’s been an agency priority for the past three decades.

Last year, the Nature Conservancy identified the Appalachian Mountains as an important landscape for slowing climate change and protecting biodiversity.

This mountainous terrain in Tennessee has experienced significant environmental impacts. Mountaintop removal mining, a form of coal mining, was the primary cause of land cover change in Central Appalachia. At least 2,300 square miles have been cleared for mining activities since 1970, according to a recent study in PLOS ONE.

Courtesy Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency

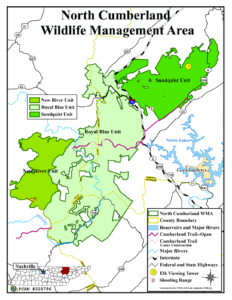

Courtesy Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency The North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area is maintained by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

The Cumberland Forest Project manages about 250,000 acres in the area, and it will continue to oversee the daily operations at this site, which sits within the North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area.

The group might generate revenue through timber, hunting and fishing sales, companies looking to offset their carbon emissions, and leases for renewable energy.

The sale represents the largest state-held conservation easement ever, and it will be overseen by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

TWRA will have the permanent right to manage the property for public recreation access and wildlife habitat. The state may also develop a multi-use trail program, Lynch said.