Tennessee’s all-out abortion ban goes into effect Thursday. When the legislation was originally introduced, lawmakers said it included an exception for the life of the pregnant person. But lawyers say the reality of the law is much more complicated.

Back in April of 2019, Republican Rep. Susan Lynn stood in front of lawmakers on the house floor. She was pushing the Human Life Protection Act – a bill that would later outlaw all abortions in the state if Roe vs. Wade was overturned.

“We want to be proactive,” Lynn said, “to ensure that Tennessee continues to help lead the way, to the fullest possible protection for human life.”

When the floor opened up for questions, Democratic Rep. Gloria Johnson challenged Lynn.

“Are there exceptions here for rape, incest, life of the mother?” Johnson asked.

And Lynn responded, “No there’s not.”

But then, she backtracked.

“This bill does protect the life of the mother,” Lynn said. “There is an exception for the life of the mother.”

Here’s the thing: the law, as it’s written, does not include the word “exception.”

Chloe Akers is a Knoxville-based criminal defense attorney. She says it’s a big problem that lawmakers need to fix.

“Our legislature very likely believed it passed a bill that had an exception for the life of the mother,” Akers says, “but it didn’t.”

Instead of including an exception, Tennessee’s ban has something called “an affirmative defense.”

“Understanding the difference between exception and affirmative defense is critical to understanding why so many folks in Tennessee are very, very scared right now,” Akers says.

The affirmative defense

Under Tennessee’s new law, a physician who provides an abortion opens themselves up to being charged with a class C felony. Period. No matter the circumstances.

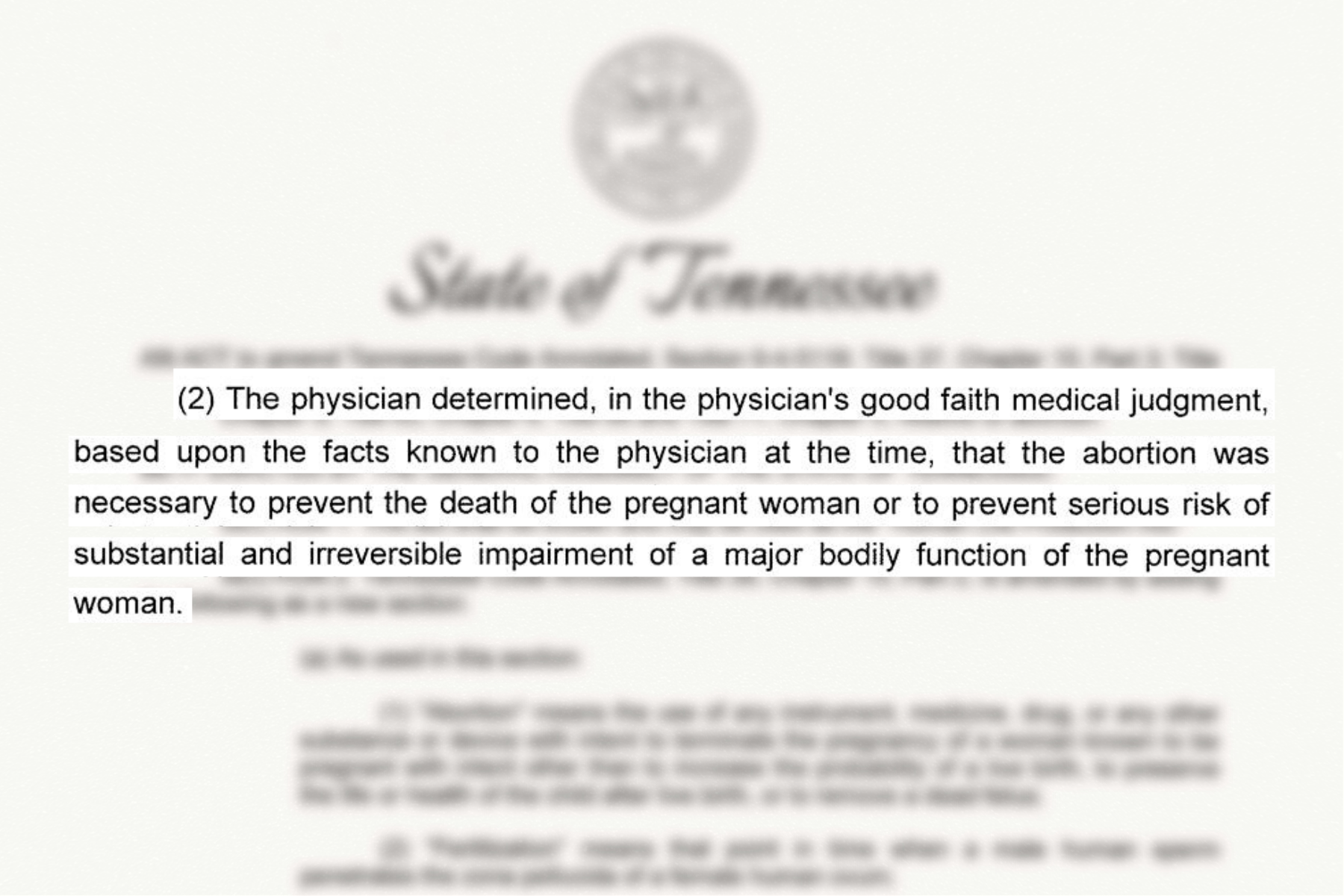

But — if they are charged, they have an opportunity to prove that the procedure was necessary — either to prevent the patient from dying or to prevent serious risk of what the law calls “substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function.”

“What is a serious risk? What does a substantial and irreversible impairment mean? What’s considered a major bodily function?” Akers asks. “These are all questions that are not answered by the statute. And they’ve put that burden on the provider, but they’ve given the provider absolutely no direction about how to prove it.”

Akers says the abortion law is very broad and the defense is very narrow — making it easy on the state to prove its case, but hard on the doctor.

Conservative lawyer Paul Linton wrote the bill and others like it. He told a group of Tennessee lawmakers in 2019 that that was by design.

“This is a very narrow defense that applies only in very narrow circumstances,” Linton said.

The reality of the law

The difference between an affirmative defense and an outright exception might seem like semantics. But not to the director of Metro Nashville’s legal department, Wally Dietz.

“Think about this,” Dietz recently posited at a press conference. “A medical provider, faced with a very sick patient who has an urgent medical condition, has to weigh the risk of providing medically necessary care against the risk of being prosecuted for a crime that could put them in jail for three to 15 years.”

Weighing those risks could lead to hesitation, Dietz says, during a medical emergency when every second counts.

“That is the reality of where we are in Tennessee today,” Dietz says.

Tennessee’s new law is most similar to Idaho’s — which was challenged by the U.S. Department of Justice.

A challenge like that hasn’t reached Tennessee, even though the state has one of the most conservative abortion laws in the nation — with no exceptions for rape or incest, and an untested defense for the life of the patient.