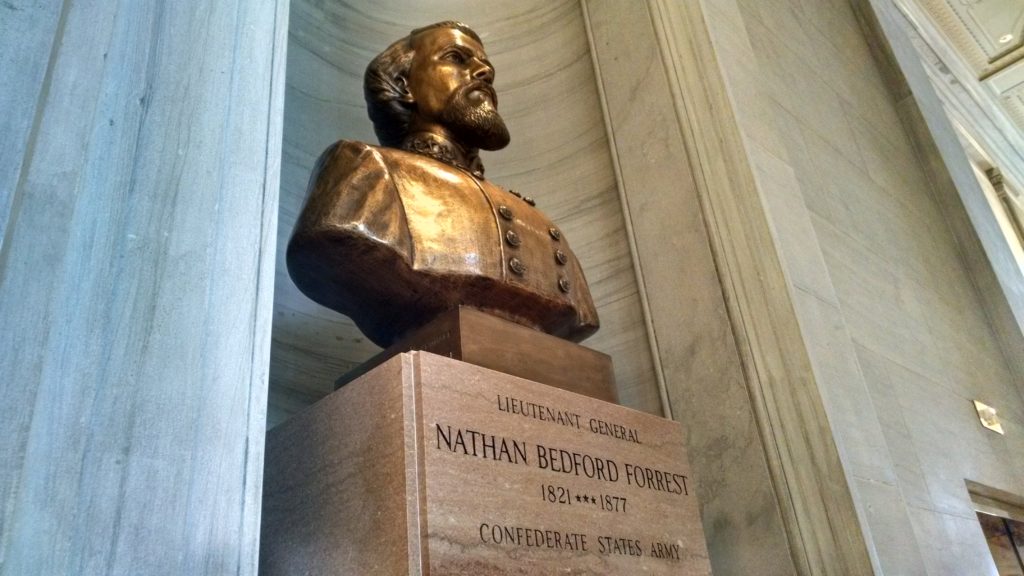

More than Sherman, more than Lee, more than Grant. A century and a half later, people are still arguing about this Civil War officer.

Within the past few years alone, people have fought over a Memphis park named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, a proposal to offer a license plate honoring him in Mississippi and plans to expand a memorial to him in Selma, Ala. Forrest High School in Jacksonville, Fla., is currently in the process of picking a new name after a petition drive convinced that city’s school board to distance itself from the lieutenant general.

While some admire the fearless leader, whose unorthodox tactics confounded the enemy, others remember him as a man responsible for racial atrocities.

Victory Against The Odds

Nathan Bedford Forrest never called the shots at the biggest, most pivotal battles. His most important fights took place far from the front lines and had little effect on the overall war effort. But there is almost no other individual from the Civil War who still gets so many people fired up. Two unusual battles in 1864 help explain why he’s the one people still rally around — and against.

Nathan Bedford Forrest grew up poor in tiny Chapel Hill, Tenn. He was, by some accounts, functionally illiterate, and he didn’t have any military training. However, he was clever.

On June 10, 1864, his small regiment spotted Union soldiers on a wooded road in rural Mississippi. The federal force outnumbered his by two to one, but rather than waiting for reinforcements, he decided to trick his enemy.

The general formed an attacking line, giving the impression that there were more soldiers in the scrub oaks. Bugle calls were issued to make it seem as if he had troops in every direction. He timed a cavalry charge against Union men on foot so that his wool-uniformed enemy had to run several miles during the hottest part of the day.

It was a trouncing, said Matt Atkinson, a historian with the National Park Service. When all was said and done, the number of federal troops killed, wounded or missing was five times as high as the Confederate losses.

Victories like that one at Brice’s Crossroads repeatedly seemed to make good on a statement that historian Ridley Wills’ great-grandfather made early in the war: that Forrest was “a bold, daring fellow, as brave as a lion.” He got the attention of Union General Sherman, who called him “that devil” and devoted a lot of energy and men to keeping Forrest away from his own march through Georgia.

It took a while for the highest levels of Confederate command to appreciate the tactical master they had in the uneducated man — they kept him off to the side for much of the war, harassing enemy supply lines — but over time, Confederates of all stripes came to love the idea of a scrappy, fearless country boy who kept outsmarting the Yankees.

People wrote songs praising him, and stories about him took on an almost mythical turn. He was said to have saved men from burning buildings, and that 30 horses were shot out from under him. Even today, his name turns up nearly 2,000 items for sale on Amazon and a whole slew of YouTube videos, from people standing in front of Forrest monuments to a pastor preaching on the Southern officer.

A Darker Reputation

But hero is not his only title you’ll find for him online. At protests around monuments to the officer, he’s also been called a “domestic terrorist” and “a man who slaughtered black folks.” A song by the Nashville band Lambchop calls him “featured artist in the devil’s chorus.”

The list of objections against Forrest begins before the war, when he made a fortune in the slave trade: His Memphis slave pen was well-known and prominently advertised. He rented out men to the railroads and ironworks and sold people to huge plantations in Louisiana and Mississippi.

During the war, when his numbers started to dwindle, Forrest recruited about a thousand locals who hadn’t enlisted in the Confederate Army. The rough men were undisciplined, but historian Bobby Lovett says they were no strangers to fighting. He calls them “just pure guerrillas” who were raiding throughout West Tennessee.

In the spring of 1864, these men marched with Forrest to raid a small federal outpost north of Memphis called Fort Pillow. Most of the Union troops inside its walls were the kind of people Forrest’s men hated the most: freed black men and Tennesseans who had sided with the North. Almost all of them were inexperienced.

Forrest demanded surrender. The Yankees held steady. Then he threatened to kill them all if they didn’t hand over the fort. And, as Wills puts it, “he damn well did.”

The battle was only fifteen or twenty minutes long, but Atkinson says the final, official tally of Union dead shows a slaughter: 66 percent of the black soldiers and 35 percent of the white soldiers were killed. But just how did they all die?

The first-hand accounts are maddeningly contradictory. At best, they tell the story of level-headed troops riding roughshod over a clearly confused enemy. At worst, they detail atrocities: soldiers killed while on their knees in surrender, wounded men burned or buried alive, buildings full of people closed tight and set on fire, a wounded Union officer nailed to a wall.

A Congressional investigation later determined the Confederate’s actions amounted to war crimes. Lovett, agrees, characterizing Fort Pillow as a “racial massacre,” with some of the worst treatment handed out to the women and children — especially black ones — who lived outside the fort. Even so, he’s doesn’t lay the blame directly on Forrest. Lovett says he doesn’t think Forrest ordered his men to commit war crimes — but Forrest didn’t exactly reprimand his men, either.

Fort Pillow alone probably would have been enough to make Forrest a hated man for a very long time. But even after the war, he most likely became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. It cemented his pair of reputations that still comes up around the South today: as a hero devoted to the Southern cause — or a racist monster.