Nearly half of entry-level security positions at Tennessee prisons are unfilled. Now, outgoing Correction Commissioner Tony Parker is urging the legislature to boost pay.

The state has struggled to recruit and retain correctional officers for years. The pandemic has only exacerbated the staffing shortage — and the dangers it can cause behind bars.

State-run prisons are short about 1,200 security officers, officials testified at a hearing of the state Senate corrections subcommittee this week. In some facilities, more than half of jobs are unfilled.

That’s meant long hours and tough conditions for those who are showing up to work. The Department of Correction has already gone over its overtime budget for the year. And now, several prisons are leaving beds empty because there’s no one to guard them.

Screenshot

Screenshot Tennessee Department of Correction Commissioner Tony Parker testifies at a senate hearing Wednesday.

“You have those critical posts, and you do your best to fill those critical posts — these housing unit assignments, emergency response, your perimeter security, your central control — those posts that have to be filled,” Parker testified Wednesday. “And I’m proud to say that, as a department, our staff has really stepped up to protect their own and to come to our own aid.”

At this point, he said, the department has not called on the Tennessee National Guard for help.

But inside the prisons, many say the circumstances are dire. WPLN News has interviewed dozens of people with loved ones behind bars during the pandemic, describing facilities so short on staff that they feared the employees were no longer in control.

In-custody deaths are close to exceeding last year’s already high total, with two months left in the year. That’s partially due to an aging prison population. In 2019, the governor’s criminal justice investment task force found that, unlike in many states, the number of people behind bars in Tennessee had increased 12% over the last decade, because people were serving longer sentences and getting released on parole less often.

Some of the deaths were from COVID, though there were many fewer documented coronavirus cases in Tennessee prisons this year after a spate of deadly outbreaks early on in the pandemic. TDOC reports that 53 people housed in their facilities and six employees have died from COVID, with some autopsies still pending.

But it’s not just health-related deaths. Officials testified that suicides and overdoses have both increased this year, due at least in part to supplies of heroin laced with fentanyl making their way into prisons — both in Tennessee and across the country. That’s even though facilities were closed down for visitors and volunteers throughout much of the pandemic.

“The issue of visitors and volunteers bringing contraband into the facility is one segment of the equation of how drugs get in,” Parker told state senators. “We also have found that we have staff who violate their oath of office and bring drugs in.”

Sen. Jeff Yarbro, D-Nashville, asked Parker if, with vacancy rates so high, the department might run the risk of hiring unqualified officers out of desperation. Parker said the key to getting better employees is upping pay.

“There’s no question that we have, on occasion hired people that we should not have hired, to fill vacancies in some cases,” he said.

Historically, Parker added, prisons have received spending boosts after “serious and bad incidents.”

“I hope we in Tennessee look forward,” he said. “This issue of staffing is not going to go away. We need to invest and become competitive in the job market, where we can hire high-quality people to fill these jobs that are most difficult on the best of days.”

Recent pay increase had pre-pandemic success

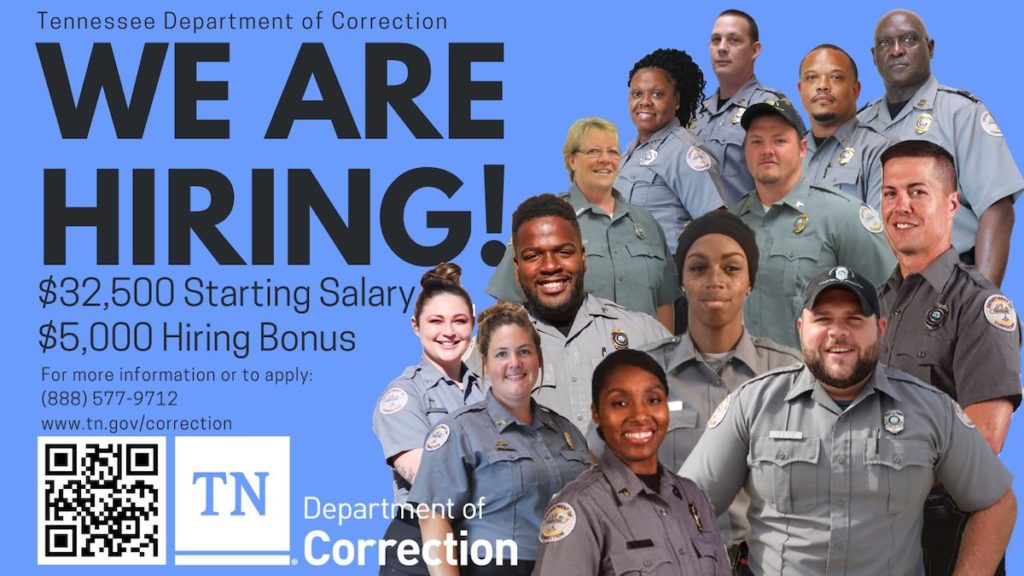

Two years ago, the state legislature added more than $21 million to TDOC’s budget to increase starting pay for correctional officers and counselors to $32,524. That added about $5,000 to entry-level employees’ paychecks.

In the first six months after that pay raise, officials testified, the department of correction hired 60% more officers than the six months prior. They said turnover also decreased in the first year, as well as vacancies.

But once the pandemic hit, it got harder to hire and retain employees. Correctional facilities became coronavirus hot spots, and many walked off the job out of fear for their safety.

This week, the department announced that it would be expanding eligibility for part-time employees, to make it easier for people to fill in open shifts at staff-strapped facilities. In the past, only former correctional officers with at least a year of full-time employment could work part time. Now, both current and retired law enforcement officers, former TDOC security staff and new hires with no past experience can all work part time. Officials said the department is training non-security employees, as well, to fill in for open security assignments.

In April, TDOC also introduced a $5,000 sign-on bonus for new correctional officers and a $1,000 bonus for employees who refer someone to the job. But so far, officials say, that program has had a “marginal” impact on hiring.

Tennessee has fallen behind nearby states, which have also increased their pay to mitigate staffing shortages. Virginia, for instance, pays entry-level officers $37,439 and is thinking about raising that number even higher. Other correctional agencies in the state, including the Federal Bureau of Prisons and local sheriff’s offices in major cities like Nashville and Chattanooga, also offer higher starting salaries. Officials worry potential employees could take jobs elsewhere that pay more.

Parker said TDOC needs to catch up. But he also said the state could save money by thinking more critically about who ought to be locked up in the first place.

“For people that we may be mad at but we could supervise under correctional supervision in the community at $4 a day versus housing them in a facility at $80 a day,” Parker said, “that’s a question that we should all be asking everyone that has anything to do with the justice system, that makes the decision on who goes to prison and who does not.”