The Nashville Predators hit the ice for the first time in 1998. Since then, the team has become a pretty important part of our city. The logo, a snarling saber-toothed tiger, is plastered all over town: billboards, yard signs, bumper stickers and merchandise galore.

I had heard that the team’s symbol was inspired by a real saber-toothed tiger that once roamed the area we now know as downtown Nashville. I wanted to know more about the original Nashville Predator, so I set out on a journey that would take me all the way back to the Ice Age.

My first stop: a home game at Bridgestone Arena.

Anyone who has been to a Preds game can tell you that they really get into the saber-toothed theme. There’s Gnash, the mascot, who is entirely less intimidating than the menacing cat in the logo. There’s the giant saber-toothed cat head with glowing eyes that descends onto the ice at the beginning of every game. There’s the growling sound effects that ring throughout the arena after each Preds goal.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN News Preds fans raise “fang fingers” towards the ice during a home game against the Ottawa Senators on March 29, 2021.

And then there’s the fang fingers. During every power play, intense, horror-movie-style music plays and fans raise and lower two curled fingers toward the ice, like the cat’s iconic fangs, clamping down on its prey.

Many fans I spoke to had no idea where their team’s name and logo came from. Others said they heard a saber-toothed tiger skull was dug up when they were building the arena.

They’re almost right.

During the summer of 1971, construction crews were hard at work, blasting away tons of solid limestone to lay the foundations for the First American Center (now the UBS Tower). They were about three quarters of the way done when they hit a narrow crevasse filled with dirt. Not long after, construction ground to a sudden halt after a worker noticed a strange-looking white object in the debris.

“That’s the tooth that started it all, the saber tooth,” said John Dowd, a member of Southeastern Indian Antiquities Survey, the group of dedicated amateur archeologists who were brought in to excavate.

In a uniquely Nashville turn of events, Dowd said that the group’s president, Bob Ferguson, was out fundraising with country music stars when he got the call.

“Bob Ferguson had been at Johnny Cash’s house. And Johnny Cash had wrote him a check for $10,000 to help our organization out,” he said.

Construction had already damaged and mixed up a lot of the findings by the time they got to the site. But Dowd and his colleagues still managed to recover a partial saber tooth cat skeleton, including one of its long, namesake fangs.

“We had no idea what was there. We just thought it was more animal bones and just a common thing. But once we seen there was some real early stuff in there, we got excited about it,” he said.

Almost 40 years later, Dowd published a report detailing the SIAS’s excavation of the First American Cave Site in The Tennessee Archeology.

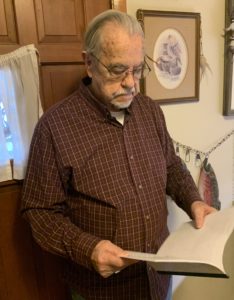

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN News John Dowd holds a copy of the report he wrote for The Tennessee Archeology.

Dowd, who is now 90, doesn’t really follow hockey. He had no idea the Predators had been inspired by the fossils he helped uncover until they announced the name and logo to the public in 1997. But it doesn’t bother him.

“We had no dealings with them, good or bad. That they use that as an emblem that was fine with us. It didn’t hurt nobody,” he said.

Ok, so that’s where the team got the idea. But I was still curious: what was the Nashville Predator like when it was alive? To find out, I met with Vanderbilt paleontologist Dr. Larisa DeSantis.

First thing’s first: this was a big animal.

“We’re talking bigger than an African lion,” DeSantis said.

The fossils found in the cave under the UBS Tower were a specific species called Smilodon fatalis. Smilodon refers to the shape of their saber-like teeth, and fatalis means deadly — which they were.

Those big, curved fangs? Not just for show.

“The purpose of the large saber is basically to let the prey bleed out very quickly, so the predator would have had less of a chance to get injured by those prey,” DeSantis explained.

Dr. DeSantis’ office is a veritable museum. Stuffed toys of Ice Age animals perch on an armchair. A taxidermied coyote is mounted, mid-leap, by the door. Even the curtains are covered in a pattern of fossils. And her shelves are full of life-size casts of fossils, including a Smilodon fatalis skull, which she got out to give me a closer look at its famous teeth.

“It’s sort of almost like a two-knife edge, so you’ve got a sharp edge on both sides,” she explained.

Dr. DeSantis studies a ton of different kinds of ancient animals. But she has a soft spot for saber tooths.

“Sometimes, they get a bad rap for being fierce apex predators and killing prey, which they have to do to eat. But in fact, these may have been compassionate kitty cats,” she said.

There is evidence that Smilodon fatalis was social, and lived in groups. And fossils have shown that some of these tigers survived injuries that would have made it difficult to hunt and eat. That suggests that others in the pack were allowing them access to their prey, and maybe even bringing them the softer, easy-to-eat bits of the carcass.

So, the original Nashville Predator was a team player, too.

Today, the entrance to the cave where the Nashville Predator was found is located at spot No. 34 in the basement level of the UBS Tower parking garage, covered by a heavy metal hatch. The fossils themselves are on display at the guest center in Bridgestone Arena. Or so we thought.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN News Parking spot No. 34 in the basement level of the UBS Tower parking garage. The metal hatch covers the entrance to the First American Cave site.

The fang in the showcase is actually a replica from an entirely different Smilodon fatalis skull found way out in the La Brea Tar Pits California.

It turns out the original went missing sometime before 1990, years before the Nashville Predators came to town. The fossils were originally housed in a case in the building we now know as the UBS Tower. At some point, they went missing, but no one noticed until the building was purchased by a new owner.

To find out what happened, I paid a visit to the Tennessee Division of Archeology, where I found Aaron Deter-Wolf, an archaeologist who actually worked for the Preds on the ice crew for a couple of years there in the 2000s.

The Tennessee Archeology Volume 5, Number 1

The Tennessee Archeology Volume 5, Number 1 These bones, including the saber tooth fang at the bottom, were discovered at the First American site in 1971.

“Over the years, that display got reorganized a couple of times as the bank was bought and sold to different organizations. And at a certain point, the fang disappears off display,” said Deter-Wolf.

He heard rumors that the fang was sent to the Smithsonian, or maybe the Carnegie.

“In researching this site in the last two or three years, I ran down all of those leads that I could, and none of those institutions have any record of ever getting a transfer of that thing. So it has disappeared. We do not know where the predator fang is today,” he said.

Deter-Wolf has his own theories about where it might have ended up.

“I think it was probably on someone’s fireplace mantle in Greater Nashville at a certain point in history, and I don’t know where it would be now,” he said.

“There was an opportunity, and the fang walked away.”

So we may never know. But we do know one thing: the Nashville Predator lives on in Bridgestone Arena, not far from where it roamed 10,000 years ago.