If you drive out to Gallatin and go down Blythe Street, you’ll come across an empty lot sandwiched between a housing development and a barbecue joint. It may not look like much, but this lot was the site of America’s oldest Black-founded fair.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN NewsThe old fairgrounds on Blythe Street, which once hosted the Sumner County Agricultural Fair.

In the decades after Emancipation, Black communities across the South began founding their own county fairs. And the very first was the Sumner County Fair, which was created right after the Civil War and ran every year until 1977.

“It was just something to behold. There will never be anything like the Gallatin old Negro Fair. Never, nowhere,” said Patrica Kelly Adams.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

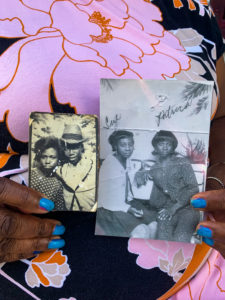

Rose Gilbert WPLN NewsPatricia Kelly Adams holds two photos of herself at the fair. The one on the right is of her and her older sister. The one on the left is of her and her husband in 1965.

It’s been over forty years since the last fair, but Adams still remembers everything — from the outfits she wore to the smell of the home-cooked food that was served. For her, the fair wasn’t just a historical institution; it was an important part of her childhood and the place she met her husband, Jimmy Kelly Jr., in August of 1965.

“I’m telling you, I just never got it out of my head. I just wish my daughter could experience some of it.”

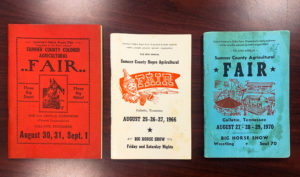

Velma Brinkley is a local historian of Sumner County’s Black communities. She’s collected a number of relics from the fair, including original posters and souvenir booklets. She explained that the fair was founded by six local African American men: John Banks, Willis Baker, Doc Blythe, Henry Ward, Mac Randolph and Arthur Banks.

“Those six men were able to weather several wars. They carried that fair through the Great Depression, through fire,” she said.

Bill Ligon and Andrew Turner grew up going to the fair and performing as part of their school band. Ligon explained that there was also a white county fair, but it was not safe for Black residents to attend.

“You did not socialize or fraternize with these people because you knew that was dangerous,” he said. “We were persona non grata just about everywhere you went. So you literally clung to where you were welcome and where you could have a pretty good time.”

That’s what made the Sumner County Agricultural Fair so important. Although white farmers attended, it was really created by the Black community, for the Black community.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

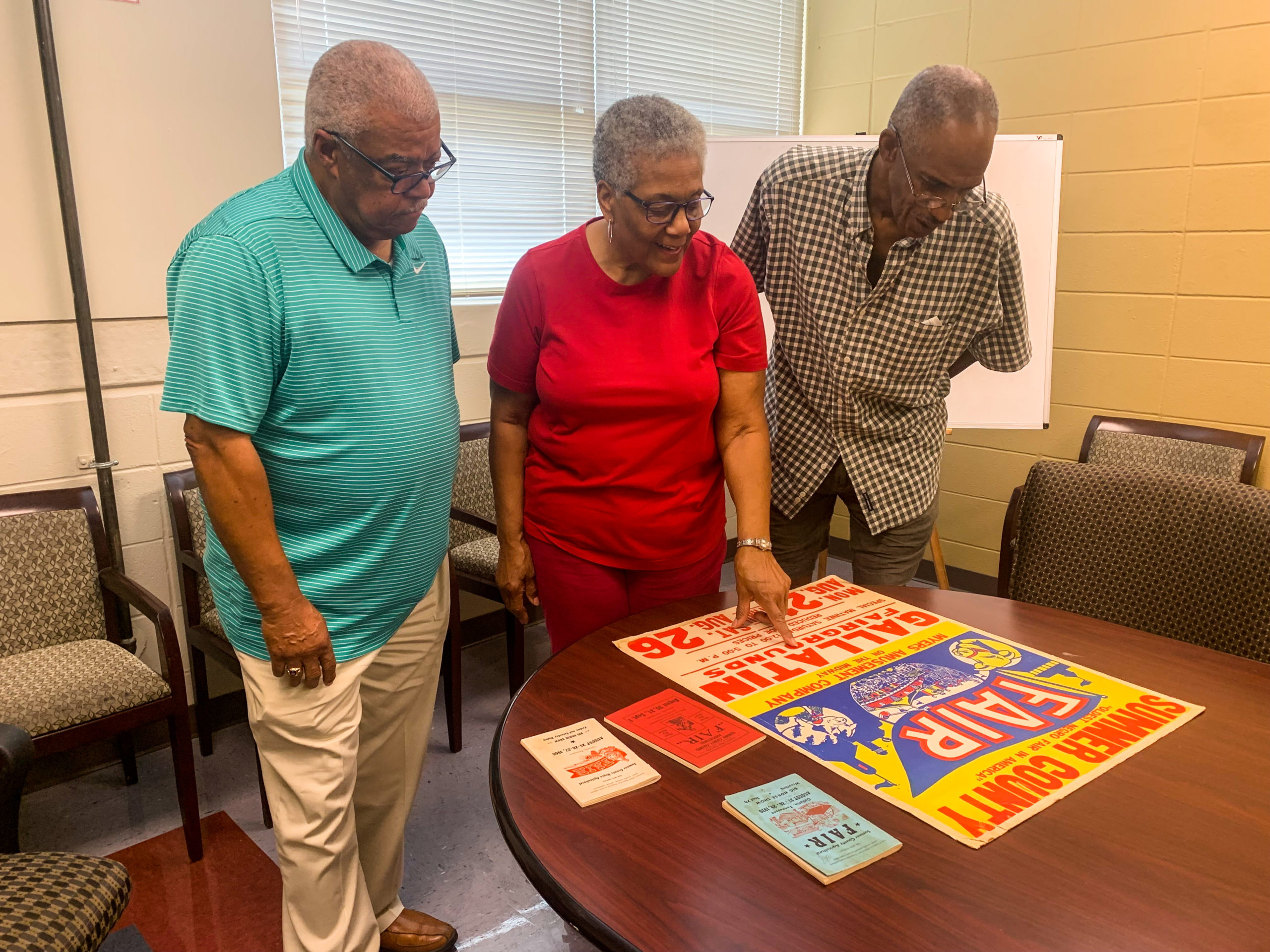

Rose Gilbert WPLN News(Left to right) Andrew Turner, Velma Brinkley and Bill Ligon discuss a poster advertising the Sumner County Agricultural Fair.

There were competitions — with awards for the best jams, flowers, vegetables and livestock in the county. But Ligon said the competition didn’t end there.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN NewsAn original poster advertising the fair

“You were always either trying to outdo the guy next to you,” Ligon said. “You were trying to out-dance this guy over here. You wanted to look better than this person over here.”

Ligon, who is a retired attorney and former Detroit Pistons player, said the fair had a lasting impact on the way he approached life.

“I learned competition here.”

And fashion, Turner said, was the biggest competition of all.

“Nobody was shabby going into the fair. You dressed up. If you didn’t get your hair cut on a particular night, you didn’t go,” he explained.

Everyone dressed to the nines — with women in evening gowns and men in hats and three-piece suits. This was partly to impress the many relatives from big cities like Detroit and Chicago who would come back to Gallatin for the fair.

“Every Black home in Sumner County was full because whatever kind of motels there might have been didn’t rent to Blacks. That’s how the Green Book came about,” Brinkley explained.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN NewsThis is a trio of souvenir booklets from the Sumner County Agricultural Fair. If you look closely, you can see the name changed to keep up with the times.

During the Great Migration between 1910 and 1970, about 6 million Black Americans moved out of the south to seek opportunities in northern cities, away from Jim Crow laws and the threat of lynching. For those whose families had moved away from Sumner County, the fair was a chance to reconnect with their roots.

Even though the fair has long been gone, the memory of it still pulls people back. Like Chase Cantrell, whose family moved to Detroit during the Great Migration.

“I’ve been hearing about this fair for years, from my father,” he said.

His great-great-grandfather, Simon Patterson, was the second president of the Sumner County Fair. Years later, Chase decided to track him down through the newspaper archives.

The Chicago Defender curtesy of Chase Cantrell

The Chicago Defender curtesy of Chase CantrellSimon Patterson, second president of the Sumner County Agricultural Fair

One clipping, in particular, really resonated with him. It called Patterson “the Money King of the Negroes in Sumner County.”

“That title: ‘The Money King.’ It’s just interesting because there’s so many financing challenges in Detroit and that is part of my work,” he said. “It’s like, wow, I am not the first person in this line to have to think through the connections between community and money and lending and finance.”

Cantrell is the founder and executive director of Building Community Value, a community development nonprofit. He’s come to see a connection between his own work and the work his great-great-grandfather did with the Gallatin fair.

“When I think about the fair and why it’s so important to Black people in 2022, it’s the question of what we can build for our own communities,” he said.

“Coming out of the Civil War, it took real audacity for the Black people in the South to say ‘we’re going to create something for ourselves that focuses on our own joy.’ That’s an amazing example and model for me as a younger person.”