This travelogue is just one part of my dispatches from Erbil. You can read them all on the project’s landing page here.

Wednesday and Thursday — Sept. 11 and 12, 2024

My first few days in Erbil were spent exploring my neighborhood, making calls and sorting out the logistics of living in a new place.

I secured myself an Iraqi phone number, and I successfully converted my stash of U.S. dollars into dinars. (I’m particularly fond of the 500 notes, which have lamassus on them.)

As in many more cash-based societies, there are two exchange rates in Kurdistan: the official one (used by the government) and the actual one (used by literally anybody buying and selling stuff in real life).

The discrepancy between these two rates means that you are always, always better off paying in cash.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN News A 500 Iraqi dinar note, featuring a lamassu, a winged animal with a human head.

The good news is that the currency exchanges here are efficient, well-run places. You hand over your money, a teller pops it into a counting machine and hands you back a stack of crisp dinars. The (actual) exchange rate is standardized and posted outside on LED signs. No funny business.

This was totally different from my experience a couple years earlier in Beirut, where all official exchanges were for suckers. I remember getting a good deal by exchanging my money under the table at a gold shop. On the advice of a neighbor, I spoke only in French. All funny business.

So, I had made it to Erbil. I had dinars, I had a working phone, and I had meetings set up with sources for weeks to come. Now, I needed to get a real understanding of local politics. I needed to find a good translator or two. I needed to make some friends.

In short, I needed to meet some local journalists.

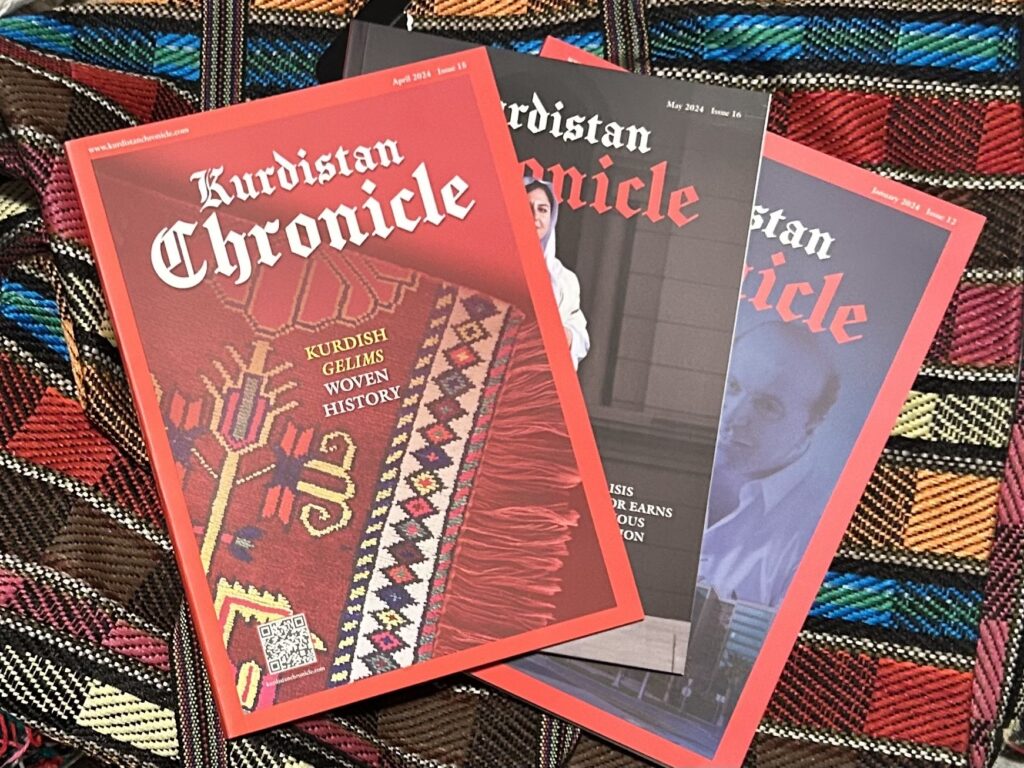

My first introduction to Erbil’s media scene was through Wladimir Van Wilgenburg, a Dutch reporter and analyst who is currently head of news at the Kurdistan Chronicle.

More: Liquor stores and LED crosses

I met him for an evening tea at Le Daff, the Ankawa restaurant he and his wife run. It’s an upscale spot with high ceilings, whitewashed walls and heavy, comfortable chairs.

Wladimir was kind enough to entertain my many questions about the minutiae of Kurdish politics. (It can be so hard to get a sense of all the proper nuances from afar.) There was an election coming up — an election that had been repeatedly delayed — so there was a lot to talk about.

He gave me brand-new copies of the past three editions of the Kurdistan Chronicle, a mayor’s phone number, and an invitation to a traditional Kurdish music concert that the restaurant was hosting that week. I recognized the magazine: I had read it online, but I had also seen copies in Nashville, at Kurdish restaurants and at the Salahadeen Center, Nashville’s Kurdish-founded mosque.

Rose Gilbert WPLN News

Rose Gilbert WPLN News A traditional Kurdish music concert at Le Daff.

Because of Wladimir, Le Daff is something of a gathering place for local media.

It was at Le Daff where I met Paul Iddon, a genial Irish journalist, and his lovely wife, who is a rather brilliant physics instructor.

And it was also where I met Suha Kamel, a Syrian journalist who primarily covers Iraqi Kurdistan’s refugee camps. We chatted about her work and exchanged curiosities about life in our respective countries as she smoked an extra slim cigarette. She offered her services as a fixer, to help me arrange a reporting trip to a Yazidi refugee camp (more on that in a future dispatch).

A word on fixers, for the uninitiated: When foreign reporters come to town, they hire fixers to help them find sources, arrange meetings, translate during interviews and get around safely. These fixers are usually, although not always, local journalists in their own right. They are often the difference between getting the story and going home empty-handed. They can also, literally, be life savers.

Back in journalism school, I heard a story of a Syrian fixer who posed as an American reporter’s husband to allow her to safely pass through ISIS checkpoints, at great personal risk to himself. In Erbil, I met a fixer who had been shot on the job — a fearless, smooth-talking guy who offered to take me to some of the dicier parts of Syrian Kurdistan (shoutout to Makeen, AKA Captain Cobra, who you’ll hear more about another time).

It’s also worth noting that there is a growing conversation in journalism about the exploitation of fixers, which I was conscious of when I started this trip.

The Iraq War and the Islamic State group, or ISIS, generated steady international media interest in this region for over two decades. Throughout it all, Erbil was a relatively safe hub for journalists, which meant huge demand for fixers, local knowledge and local sources.

Now, though, the world’s attention has turned to the newer conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine. That means many of the international journalists (and their international money) have packed up and left Erbil.

Wladimir, Paul, Suha and Makeen, though — they’re in it for the long haul.

P.S. I want to say how grateful I am for the kindness and patience of all the journalists in Kurdistan who took the time to answer my questions, share contacts and even just hang out and grab drinks. They didn’t have to, but they did. I hope to pay their generosity forward one day.