The correctional officer sounded flustered. He’d just dialed Trousdale County 911, but he was too distracted to provide much information.

“I have an unresponsive inmate, and CPR is in progress,” he quickly told the dispatcher.

The guard didn’t know how old the man was. He could barely hear the dispatcher’s questions over the beep and chatter of his radio. But the 911 operator assured the officer and sent paramedics to 140 Macon Way.

Courtesy Elizabeth Hudson

Courtesy Elizabeth Hudson Terry Deshawn Childress died on Feb. 24, just one day after his parole hearing. The TBI is investigating his death as a homicide.

The unresponsive man was 37-year-old Terry Deshawn Childress. He was pronounced dead on Feb. 24. State agents suspected he was killed and launched a homicide investigation.

Not including executions, Childress’ death marked the 17th homicide in a Tennessee prison in the past five years. All but three of those deaths occurred at private facilities, even though they house only about a third of the state’s prisoners.

Experts and loved ones worry the drive to earn a profit could be making these facilities less safe. And months after Childress was killed, his family still has questions.

“We don’t even know who did it. We don’t know why he did it,” says Childress’ sister, Elizabeth Hudson.

She says it’s been a challenge to get any information from the private prison about what happened.

Officials may not have known him as the young man who loved football and music, who doted on his younger siblings and nieces and nephews. But Hudson did.

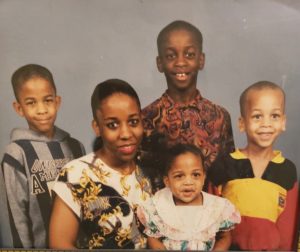

Courtesy Elizabeth Hudson

Courtesy Elizabeth Hudson Terry Deshawn Childress, center, poses for a family portrait with his mother and younger siblings as a child.

“If anything was going wrong or we needed anything, it was always, ‘Call Terry.’ Terry would always be right there,” she says.

As Childress cycled in and out of jail, Hudson says she tried to encourage him to be better.

“We had several talks,” she says. “It was frustrating. … I would say, you know, ‘Terry, you’re smart, you’re more than what others are telling you.’ ”

Childress had a parole hearing the day before he died. After multiple stints behind bars, his sister hoped this time he would get out and stay out.

“I just feel like this last time that he was in there, he was able to gather himself together mentally and to come out to be better,” she says. “I know once he was to get out, it would have been a different story.”

Hudson’s family feels like the prison failed her brother.

And that it should be shut down.

“They’re supposed to be protected, you know what I’m saying?” Hudson say. “And y’all aren’t protecting them as you should.”

‘A sign of very a serious dysfunction’

Homicides inside a prison are a failure of correctional facilities’ No. 1 job, says David Fathi, director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project.

“The paramount task of any prison is keeping people safe. Prisoners, staff, visitors, everyone,” he says. “If the prison can’t do that, it’s a sign of a very serious dysfunction and a breakdown in the prison’s most fundamental mission, because a prison is an environment of total control.”

Fathi says multiple factors could make facilities unsafe, from staffing shortages and poor training to the way states classify which people should be housed in which prisons.

Chas Sisk WPLN News

Chas Sisk WPLN NewsDemonstrators in Nashville protest Brentwood-based CoreCivic during a march in 2018. The company has been a frequent target of critics of mass incarceration.

But the biggest problem, Fathi says, is when prison operators prioritize costs over security.

“It is not the case that every private prison is worse than every public prison. There are some truly awful public prisons out there,” he says. “But there is substantial evidence that, on the whole, on average, private prisons are simply less safe.”

National data back up his claims.

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that privately operated federal prisons had higher rates of assault than Bureau of Prisons-run facilities. The DOJ found that federal prisons operated by CoreCivic (then called Corrections Corporation of America) “had the highest rates of inmate fights and inmate assaults on other inmates.”

Fathi says that’s because private prisons take on an “essentially impossible task.” They have all the same responsibilities as state-run penitentiaries, but they’re supposed to do the job more cheaply and make a profit.

Chas Sisk WPLN

Chas Sisk WPLNCoreCivic has been criticized by local criminal justice reform advocates for reports of poor conditions at its facilities.

“The fundamental problem is that we, as a country, want to do mass incarceration on the cheap,” Fathi says. “We have the highest incarceration rate in the world, and yet we invest much less than our peer nations in making sure that our prisons comply with basic standards of health and safety.”

Brentwood-based CoreCivic operates all of Tennessee’s private prisons. In an email, spokesman Ryan Gustin says the company never cuts corners on safety and that its staff receive extensive training. He says violence happens at its facilities because they house people convicted of violent crimes.

The Tennessee Department of Correction says that the company houses prisoners who are authorized for minimum to medium custody. A spokesperson declined to comment on Gustin’s claim that CoreCivic facilities hold “a higher concentration of inmates convicted of murder or other violent crimes.”

But after an audit in 2017, the state fined CoreCivic more than $2 million because its facilities were dangerously short-staffed. Last year, auditors found its prisons were still understaffed.

And Michelle Long says her son is worried he could be the next person killed at their Trousdale Turner facility.

‘You’re helpless’

“He’s afraid that what happened to the guy next door, you know, is gonna happen to him,” she says.

Long says her son could hear the attack from inside his cell. And that he heard Childress pound on the door for help that came too late.

“He called me and he said that he was scared and that there was nobody over there anymore,” she says. “And he told me how the guy was killed.”

Long’s son was transferred to Trousdale in November, after serving at several other facilities for a sexual battery charge. And she immediately noticed a change.

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsA staff desk in Trousdale Turner’s visitation room sits empty as the room is closed off for a special event in Oct. 2019.

She says her son often goes weeks without calling when the prison goes into lockdown because there aren’t enough staff to monitor the common areas.

CoreCivic says this is false and that there’s always a backup plan when staffing levels get low. The company also says it has upped the starting salary at Trousdale to attract more applicants, and that the facility now has the highest starting pay of any prison in the state. But CoreCivic has repeatedly declined to share staffing data with WPLN News.

“We do not release information to the public that could be used by an individual to compromise safety or security at our facilities, and staffing information could be used in that manner,” Gustin says. He adds that “we do not have vacancy rates at any of our TDOC facilities that we believe create a security concern.”

But Long doesn’t trust that the prison can protect her son.

“I worry about him every day. And, I mean, I cry on a lot of days,” she says, her voice breaking. “I don’t know if it’s better if I get a phone call or if I don’t get a phone call, because, when he calls he says such bad things. You don’t want to hear it, you know. I mean, you’re helpless. You’re helpless.”

Long is hoping her son can get moved to another prison, so she won’t have to worry as much about his safety. She knows he has to serve his time. But she doesn’t think that anyone should have to live in constant fear for their life.

Scroll through our interactive database of Tennessee prison homicides:

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member.