It’s a bright and breezy, early summer morning in Promise Land, Tenn. A crowd has gathered for the yearly celebration of the town’s history. First up, is the parade of hats — a tradition started by the late Helen Edmondson Hughes.

“You never saw her without a hat. She wore a hat everywhere,” says her older sister, Bernice Edmondson Herd.

Edmondson Herd leads the parade in one of her sister’s hats today. It’s lime green, wrapped in red hearts. Behind her are other descendants donned in bright, colorful sun hats — like Toka Nesbitt-Raney. She’s a descendant of founder and U.S. colored troops veteran John Nesbitt. It’s been 29 years since she last stepped foot in Promise Land.

Listen to the full episode on This Is Nashville: Exploring the living history of Promise Land, Tennessee

Andrea Tudhope WPLN News

Andrea Tudhope WPLN NewsTamara Alsaad, left, and Toka Nesbitt-Raney are descendants of John Nesbitt.

As she unravels her connection to this place, her eyes fill with tears.

“You can see the reinvestment into the community, where now former descendants are coming back home. And that’s what this weekend means to me. I’m just … full,” Nesbitt-Raney says.

Promise Land is a special, and rare, place. After emancipation, Tennessee did not make it easy for formerly enslaved people to realize their full freedoms. The state had laws on the books keeping them from accessing things like basic citizenship, employment and education.

So, some took matters into their own hands.

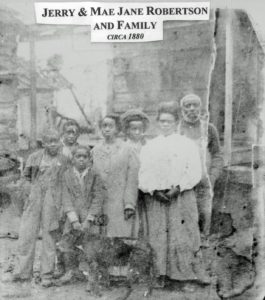

Jerry and Mary Jane Robertson and family in the early 1900s. Today one of the youngest descendants who currently lives in Promise Land is a fifth-generation descendant of the Robertsons.

It was around 1870 when these families began purchasing land in Dickson County. Washington Vanleer, William Gilbert and Jeff Edmondson were among the original settlers, along with U.S. colored troops veterans Clark Garrett, Ed Vanleer and John and Arch Nesbitt.

Today’s Promise Land isn’t quite what it used to be. But, to this day, one of the churches, and the original Promise Land School are still intact.

“Seeing the original piano, and seeing the original sewing machine, and seeing the benches and the actual desk where they sat … You can feel the history. You can feel the love,” Nesbitt Rainey says.

Hanging on each gust of this cool, early summer breeze is a memory. The air seems to be bursting with them. She’s right. You can feel it.

‘This was ours’

Looking just across the lawn at the Promise Land School where she attended, and her parents attended, descendant Nancy Nesbitt Winfield is flooded with memories.

“I almost can hear the bell ringing,” Nesbitt Winfield says.

Her great grandfather, John Nesbitt, bought the land where the school was built. Nesbitt was enslaved on a farm in Charlotte before he enlisted in the Civil War in 1863. When he returned, he was severely wounded. But that didn’t stop him from building and leaving a legacy.

“He wanted to give and pay it forward. That’s why he donated so much of the land to Promise Land,” Nesbitt Winfield says.

John’s wife, Ellen Clemmons Nesbitt, helped provide for the family by teaching the children in their community. Then, in 1880, John Nesbitt used his disability from the Army to fund a school. It originally bore their family name, before it became the Promise Land School. One of Nancy’s ancestors, D. Beatrice Langford, was a school teacher there.

“From the beginning, Promise Land grew out of hardship. People in Promise Land put their feet and their hands to the grind and didn’t look back,” Langford says with a laugh.

In its heyday, Promise Land was a self-sustained, thriving community. All within a thousand acres or so, there was the school, three churches and a few general stores, selling everything from flour and sugar to coal oil and chicken feed.

“We did work for the white people. But we owned our land. We raised our own food. This was ours,” says descendant Sylvia Edmondson-Holt.

Andrea Tudhope WPLN News

Andrea Tudhope WPLN NewsSylvia Edmondson-Holt grew up across the street from St. John Methodist Church on Promise Land Road. The church still stands today.

At its peak, there were around 50 houses in Promise Land. Teachers, like Ollie Huddleston, taught children from the 1st to the 8th grade all in the one-room schoolhouse. By 1905, there were nearly a hundred kids in attendance.

“Every day in the summer, if I was here, we would be up and down this road. I don’t know how my mother kept up with us,” Edmondson-Holt says, laughing.

Her family lived across the street from St. John Church where her dad, Theodore Edmondson, led the Promise Land Singers. They were famous for recording sessions that came to be known as ‘all night singing’ because, even after the recording stopped, they’d sing all night long. The sessions were broadcast on Sundays on WSOK and WSIX in Nashville and WVOL (then WDKN) in Dickson. They were the first African Americans to sing on WDKN in the ‘50s.

The town was brimming with life. It was on the town’s porches where Promise Land’s history was carried. Told and retold.

Living history

Serina Gilbert used to walk Promise Land Road, porch to porch, collecting its history. She is a descendant of founder William Gilbert, who had been enslaved nearby on Barton’s Creek. He later bought 59 acres down at the end of Promise Land Road, and called it Gilbert’s Town.

Andrea Tudhope WPLN News

Andrea Tudhope WPLN NewsSerina Gilbert went to Promise Land School in the ’50s. Her teacher was Ollie Huddleston. Gilbert remembers Ms. Huddleston misspelled her name once, and Gilbert was such a believer in her teacher, and her education, that she thought Ms. Huddleston must be right. She uses that spelling to this day.

“I can remember very vividly … seeing streams of smoke coming up out of the chimneys and stovepipes of homes that were back of the road, and seeing laundry hanging and clotheslines blowing in the wind, and smelling the food that was cooking … I remember the older people who were at home and not working would be on the porches,” she says.

B. Edmondson was one. Gilbert called him “Cousin Bubba.” And, let’s just say, he’s not the only cousin in town. In Promise Land, everyone is a cousin. These folks all descended from those tight-knit families who first settled here in the late 1800s.

“And if you’re from Promised Land, you know that connection. You just always want to come back. And, yes, your family is like one big family,” Nancy Nesbitt Winfield says.

Gilbert says Cousin Bubba owned the general store. But, by the time they left school, it was closed, so he’d sit on the porch and regale the kids with stories.

“Those stories still live with me now,” she says.

Descendant Essie Vanleer Gilbert at 100 years old, in 2017.

By the 1950s, the town had dwindled. A lot of families migrated north — most to Ohio. She says that school was her foundation. She ultimately left to pursue her education and career. Gilbert was one of the last students left when the Promise Land School had to close down for good in 1957. But her mom, Essie Vanleer Gilbert, never did leave Promise Land. When Serina returned in 2004, Vanleer was one of maybe two original descendants left. It was a ghost town, and Vanleer was on a mission to bring it back.

“She herself was a historian and griot who loved to share the history. And so it was contagious, having her live under my roof and sharing the oral history with me. I caught the bug,” Gilbert muses.

If only Ms. Essie could see it today.

A new era

After her return, Serina Gilbert picked up her mom’s torch and ushered in a new era for Promise Land.

“Promise Land is in every fabric of my being. I feel like a daughter to the community. So, when I talk about my ancestors, I feel very close to them, and I feel like I’m speaking as a child would about their parents. I feel that type of kinship,” Gilbert says.

She’s been volunteering as executive director for what’s now called the Promise Land Heritage Association for nearly two decades. The association earned 501(c)(3) designation back in 2004, which has helped the preservation efforts since they never received government funding. The restoration efforts have solely relied on donations from the descendants and grant funding.

Over those decades, the main road was finally paved, and the schoolhouse restored. That restoration earned it a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007. St. John Methodist Church is still standing today, too, right on Promise Land Road.

And now, families are actually moving in. Houses are being built on land still owned by the descendants of those original settlers. It’s a diverse town now, but it’s still Black-owned land.

“It feels good. It feels like life is continuing,” Gilbert says.

Most of the descendants don’t live here anymore. But those roots may be stronger than ever.

“Although we moved away when I was young, we never forgot it,” Nancy Nesbitt Winfield says. “We came back every year for homecoming, and we talked about it all the time. When I put my feet down here, I know this is my roots. This was Nesbitt land right here where I’m sitting. And my great grandfather donated this land to this community. So, it makes me feel proud. That’s why we work so hard now to preserve the school and to preserve the heritage because, even when we’re gone, we want the Promise Land to still be there for our children and our children’s children.”

Andrea Tudhope is the executive producer and director of This Is Nashville. Email her at [email protected], and follow her on Twitter @andreatudhope.