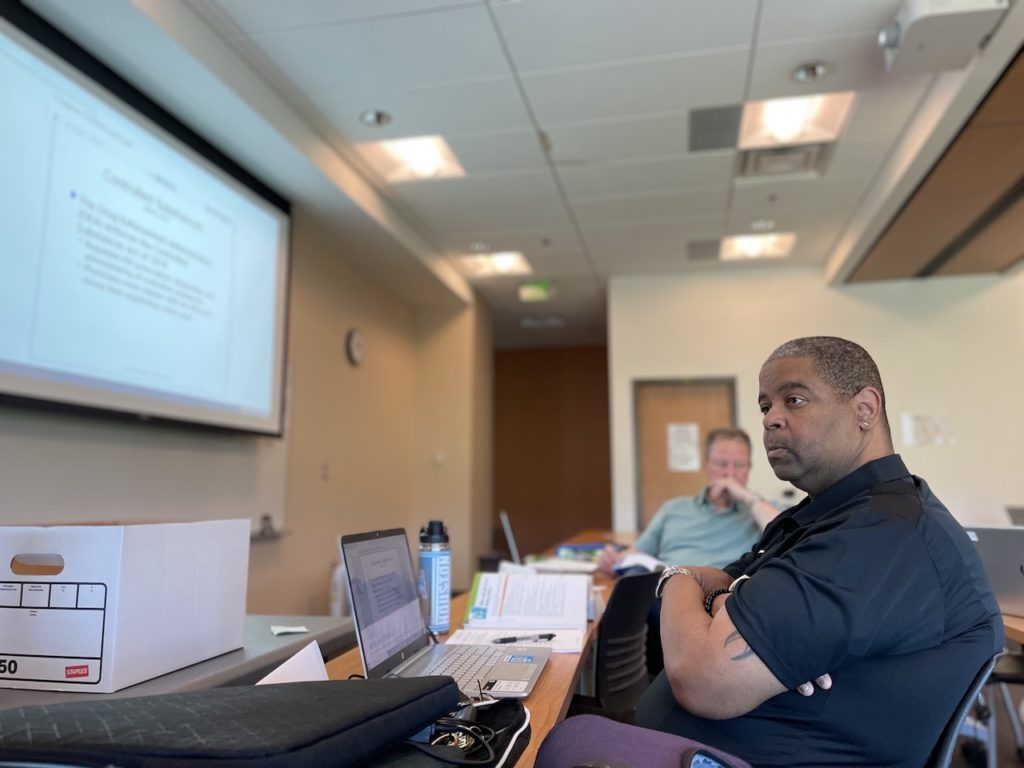

Eleven students are typing notes on their laptops at Nashville State Community College. For several, it’s been a while since they were last in a classroom.

They’re training to become medical assistants, which will take 12 weeks of work in both the classroom and in the hospital.

“Ok, we’re going to talk about drugs,” Professor Eli Alvarado told them. “Prescription pads, you need to keep them locked up, double locked.”

As medical assistants, they’ll take on roles calling in prescriptions, interviewing patients about their medical histories and taking vital signs.

Each already works at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and has for many years, but not necessarily at the bedside. And clinical roles are where staffing has become so critical. Vanderbilt has more than 100 openings for medical assistants, with people leaving all the time. So the health system put out the offer to its 29,000 employees: We’ll pay you while you train.

Clifford Johnson, 52, was the lead driver for a team that shuttles surgical instruments back and forth to get sterilized. He’s worked at Vanderbilt for seven years.

“When I was driving a truck. I just dealt with driving a truck,” he said. “I felt like I could do more in this particular field.”

Johnson said he knew there was more opportunity on the clinical side of campus. But going back to school was always tricky — even though Vanderbilt had offered to reimburse tuition.

“A lot of times, you have to go to work, then leave work, go to school, then you’ve got family. You need 28 hours in the day instead of 24, and without any sleep,” Johnson said.

But like so many hospitals, Vanderbilt is looking for creative hiring solutions. So beyond covering tuition, the hospital offered to pay employees like Johnson their salaries as they train full time.

“The turnover has been tremendous,” said Vanderbilt’s vice president for allied health education, Peggy Valentine. “So the thinking was, why don’t we work with our employees, build a sense of loyalty? And then we’ve got a workforce that’s likely to stay with us in the long haul.”

The “grow your own” concept is catching on around the country as the market for all clinical roles becomes more competitive — from a community hospital in Comanche County, Okla., to community health centers across California.

The No. 1 challenge for health care providers at the moment is staffing up and down the ranks, said David Jarrard, a communications strategist who advises health systems nationwide.

“I think they’re learning the value of loyalty and what it takes to instill it — earn it,” he said.

And it’s not just about money, though higher pay helps. Vanderbilt is upping hourly rates for medical assistants from $17 to nearly $21 an hour, Valentine said.

But it’s also about opportunity. In health care, the credentials are often “stackable,” meaning a medical assistant has an easier time becoming a surgical tech or a registered nurse, jobs that are also in high demand.

“Some people may be satisfied being a medical assistant. Others may want to go higher,” Valentine said. “It gives you a chance to sort of put your toes in the water and see if this really is for you.”

As for Clifford Johnson, becoming a medical assistant may not even raise his hourly pay. But there will be considerably more opportunity to advance. And for now, he sees that future in health care with the hospital that’s investing in his career.

“To me, this really is like the ground level of where I can go,” he said.