In 2016, the Tennessee Valley Authority did something no other utility had done in two decades: It turned on a new nuclear reactor.

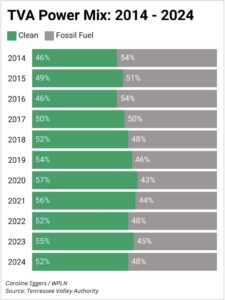

TVA sourced half of its power from fossil-free sources the following year.

By 2020, the mix peaked at 57% clean.

“We are, in fact, the greenest power system in the Southeast U.S.,” TVA CEO Jeff Lyash said at the time.

Progress has since stalled — even reversed — and the nation’s largest public power provider will still be just as reliant on fossil fuels in 2030, according to TVA’s modeling.

A brief history of TVA’s power system

TVA started building its hydropower dam system in the 1930s.

Then came coal. TVA built coal plants between the 1940s and 1960s, beginning construction on its final and largest coal plant, the Cumberland Fossil Plant, in 1968.

All nuclear plants were under construction by the 1970s. (Many nuclear projects were scrapped, including the recent abandonment of the Bellefonte project, leading to TVA’s now-roughly $20 billion debt.)

TVA fired up its first gas plant in 1972, but most gas plants wouldn’t come online until the 2000s.

In the 2010s, after the infamous Kingston coal ash spill and the dwindling economics of coal, TVA began retiring its coal plants. TVA could have then charted a cleaner path, adding renewables and preparing its system for the future, according to Stephen Smith, executive director of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

“That’s when we really started pressing them more aggressively on renewables,” Smith said.

But TVA added negligible renewable capacity during this time, and most solar additions serviced companies or corporations trying to clean their image.

Ultimately, this history means that TVA has never taken any true climate-motivated action, according to Smith.

“I honestly can’t point to a single decision that was a carbon decision,” Smith said.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsThe percentages reflect what TVA reported in financial filings to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission between 2014 and 2024.

The future of clean energy

Utilities in the Southeast could reach 45% solar in the next 10 years, saving them billions of dollars, according to a recent study by Berkeley Lab and the U.S. Department of Energy. The solar expansion was modeled with significant investments in batteries to keep the grid reliable, which has been demonstrated in other parts of the country.

Today, TVA gets 4% of its power from solar or wind.

In 2020, Lyash said TVA had about 400 megawatts of solar but was adding between “700 to 1,000 megawatts each year.” TVA now has 1,200 MW in operation, with many projects in development.

The utility promised an addition of 10,000 MW, or 10 gigawatts, of solar by 2035. However, the utility is not currently on track to meet that goal, and the draft of its latest long-term plan shows a range of adding just 3 GW of new solar or as much as 20 GW. TVA suggested “up to 4 GW” of wind and “up to 6 GW of storage.”

“TVA keeps talking a good game about making commitments to renewables, but they actually aren’t following through on it with any passion and any real speed,” Smith said.

Nuclear additions have also been floated. The Biden Administration just released a roadmap to triple nuclear capacity in the U.S., but there is less certainty with tech that has repeatedly proved expensive and time-intensive. Last year, the Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia came online seven years late and $17 billion over budget. It was the first new reactor since TVA’s Watts Bar, which took 42 years to complete and was billions of dollars over budget. (Cost risks like these eventually fall to consumers via monthly electricity bills.)

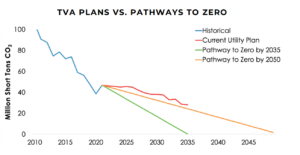

Courtesy Southern Alliance for Clean Energy

Courtesy Southern Alliance for Clean Energy The Tennessee Valley Authority will not significantly decrease its carbon dioxide emissions over the next decade.

But TVA has been consistent in one goal: rapidly expanding its fossil fuel system. Since 2020, TVA has planned nine new gas plants, which will increase capacity from fracked methane by 60%. This buildout has been widely criticized for its cost, pollution and associated “lack of transparency.”

With the election of President-elect Donald Trump, Smith suggested TVA may have even less pressure to clean up its system.

And, with all of the new gas plants coming online, TVA’s recorded carbon dioxide pollution may temporarily increase — while the unrecorded methane almost certainly will.