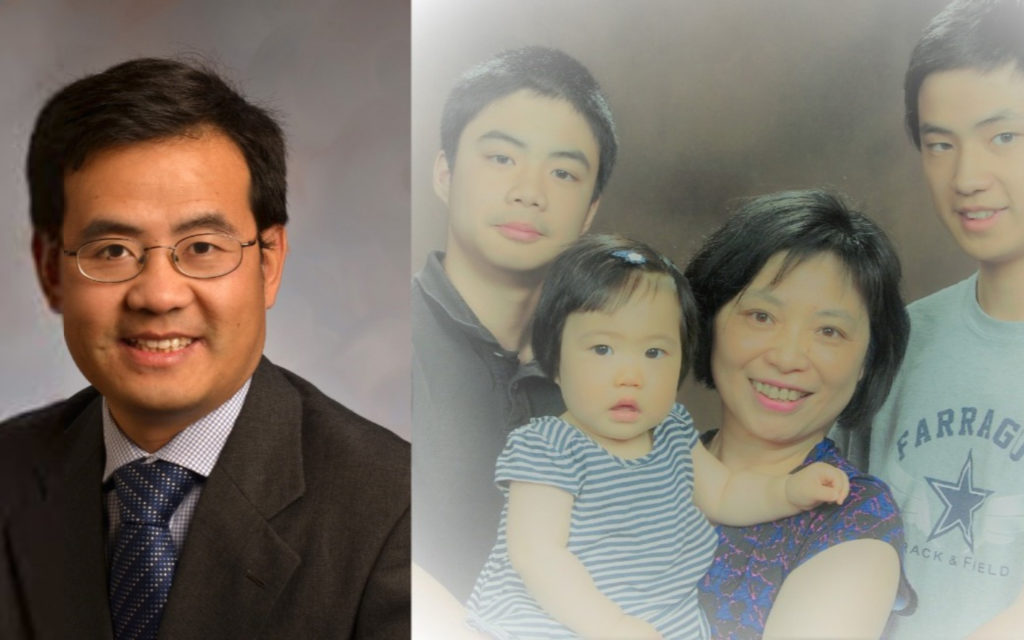

The Department of Justice is ending a Trump-era crack down on academics with ties to China. Civil rights advocates have criticized the so-called “China Initiative” for targeting professors based on their ethnicity. For one Tennessee professor, it’s been a long journey back to the classroom after his arrest.

Professor Anming Hu is a world-renowned nanotechnology expert with two PhDs, two published books and two NASA grants. And he’s been unable to work for the past two years, after the FBI accused him of being a spy for China.

“I lost the job, and I have to pay the legal fee,” Hu said. “So, I borrowed a lot of money from my relatives, from my wife, from her family … and we also get some money from GoFundMe.”

Hu was on house arrest, confined to his Knoxville home. And on paper, it was his contributions to NASA that put him there.

“That certainly is the darkest period of my life,” he said. “It’s very challenging for me to really understand what is happening to me. For the indictment, I read it several times. I don’t know why the government, you know, they think that I do the false statement, I do the wire fraud to the NASA. But I don’t want to give up my dream for continue as the scientist and the educator.”

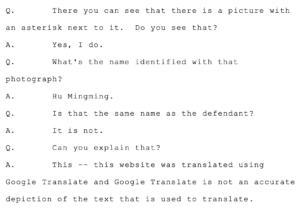

It is a complicated case, exacerbated by a language barrier.

It starts in 2018. FBI agents turned up at Hu’s office to ask about a lecture he’d given in China. It was a public lecture, so Hu wasn’t concerned.

“There’s nothing relative to national security. So due to that reason, at that time, I’m pretty open. So what they ask, I directly tell them. Later on, I know I shouldn’t discuss with them without a lawyer, but at this point, I don’t know that. I don’t know my rights,” Hu said.

The agents thought Hu could be a spy, and if he wasn’t, he could become their spy. They urged him to go to a conference being held in China and stop by the Knoxville field office afterwards to talk about what he saw on the trip. But Hu told the agents he’d already declined the conference’s invitation. He had a full teaching load at the University of Tennessee Knoxville and was in the process of applying for a NASA grant.

Months later, Hu was boarding a plane for an international conference in Japan when Homeland Security stopped him. After 40 minutes of questioning, Hu was going to miss his flight. So, the agents gave him a choice: stay in America with his phone and laptop, or leave for Japan without them.

“I decide to go without a computer, without my cell phone, without a memory stick, so just with luggage,” Hu said.

That was his first clue the FBI was still investigating him. Hu wouldn’t know it for some time, but the FBI had honed in on the NASA grant he mentioned in their first encounter. The space agency has restrictions on collaborating with non-American companies and universities, and Hu has a summer job at his alma mater, the Beijing University of Technology.

NASA had first reached out to Hu for help with a project designed to collect soil samples from Mars.

“They needed to develop a special container to hold those samples,” Hu said. “So, I joined that mission to use my technique to do the sealing of that container.”

Now, Hu was applying for a second NASA grant — and not only did the FBI track Hu’s application, they also told the University of Tennessee Knoxville to approve his paperwork.

So, it did.

UTK got the money to fund the grant research. NASA got the results. And Hu got arrested.

In the summer of 2020, Hu was in house detention. But unlike other people stuck at home during the pandemic’s first wave, Hu couldn’t legally pass the boundaries of his yard. He also had a mountain of legal fines, no source of income and no family in town. His son had been a student at UTK, but when Hu lost his visa, his son had to leave the U.S.

“I live separate from my family. They live in Waterloo, Canada. And almost every day, I try to communicate with them through the internet, through the cell phone,” Hu said. “Each night, I try to tell the one story to my daughter. When I was arrested, she’s only four years old. And now, she’s six years old. I haven’t saw her in over two years.”

But Hu says he tried to make the most of that time — exercising to keep his type 2 diabetes in check and writing about his research in nanotechnology.

By the time the trial began, the FBI hadn’t found any evidence that Hu committed economic espionage. Investigative reporter Jamie Satterfield was one of the only journalists who came back to the courthouse every day for Hu’s trial.

“I’ve covered federal cases for 20 years, and the FEDs generally put together an airtight case, and they use all the investigative tools at their disposal,” Satterfield said. “But in this case, their primary investigative effort was to do a Google search.”

A transcript of cross examination between defense attorney Phil Lomonaco (Q) and FBI agent Kujtim Sadiku (A).

At trial, a university administrator testified that FBI agents told her Hu was hiding his ties to China, and that they suspected he was a spy. So, when the agents told her to send his grant proposal like normal, she had second thoughts.

“She called a legal counsel for the University of Tennessee, and she says, ‘I’m concerned about this. I’m about to put my name on something these agents are saying is a fraudulent act,'” Satterfield said. “And she was told to do it anyway. And so she did.”

Hu’s trial ended in a deadlock last summer, and by the fall, a judge had thrown out his case altogether. That left Hu scrambling to reinstate his visa and negotiate for his old job.

“When I was acquitted, my wife said to me, ‘You should leave the U.S. immediately’ and ‘the U.S. is the dangerous country.’ But I felt I cannot. I want to continue in U.S.,” he said. “When I came to UTK, I choose the UTK and Tennessee as my place where I build my career, build my life, raise my family. So, I didn’t do anything wrong. I shouldn’t give up. I don’t want to give up. I want to continue.”

In a statement, UTK Provost John Zomchick says the school is “pleased and grateful” to welcome Hu back to the faculty.

Hu is now back in his position with tenure, back pay and $300,000 to rebuild his lab. The campus is taking a look at its own role in Hu’s case and reviewing its policies.

Meanwhile, the Department of Justice is ending the China Initiative, but some people charged under it are still going to trial. So, Hu remains skeptical.

“I welcome that, but meanwhile, I would like to keep eye open — see what’s the real action. They should avoid abuse their power. I don’t think right now is the justice. Before we learn the lessons, before we take the action to avoid a similar case happen in the near future, that’s not the justice.”