Tennessee may soon change the way it regulates wetlands.

Earlier this year, state lawmakers proposed a developer-backed bill to remove protections on more than half of Tennessee’s wetlands. That bill was defeated, but another version of the bill is expected by spring.

Officials and various advocates discussed what is at stake during a state Senate hearing last week.

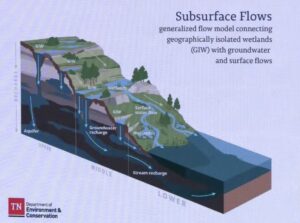

Part of the conversation centered on one scientific term: “geographically isolated wetlands,” which represent about 430,000 acres of Tennessee’s total 787,000 acres of wetlands and are the target of de-regulation legislation. But that term is a misnomer.

Isolated wetlands are, in fact, connected to our systems of water above and below ground. It’s just not obvious without looking at a diagram, according to David Salyers, commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.

“This is a poorly understood yet vital concept that needs to be understood to enable wise policy decision,” Salyers said.

People involved in the hearing also discussed “low-quality wetlands,” a term TDEC uses to reflect certain soil characteristics and plant types for regulatory purposes. These wetlands sometimes have less plant variety because of human-caused disturbances.

The term can also be misleading: There is likely little difference between low-quality and high-quality wetlands in terms of function, TDEC wrote in a report last month.

Wetlands soak up flood waters, improve water quality, provide habitat and recharge streams and aquifers.

When developers fill wetlands with concrete or asphalt to build over them, streams and rivers dry up quicker and longer during drought, according to George Nolan, the Southern Environmental Law Center’s Tennessee director.

“Then, when the rains come, there will be more intense and severe flooding without the availability of wetlands to soak up water,” Nolan said.

So, why would the state allow the destruction of a delicate slice of nature, especially when the warming climate is fueling extreme weather like flooding?

‘Driven by the financial interest of single individuals’

The issue for developers boils down to money.

TDEC made various recommendations in its report, like creating a science-based definition of wetland quality tiers and streamlining certain regulatory processes for developers. The agency suggested some of the recommendations were intended as compromises, as opposed to a blanket removal of all protections for isolated wetlands.

Most notably, the agency suggested doubling the size of wetlands — from a quarter acre to a half acre — that developers can destroy without paying into a mitigation fund for wetland restoration elsewhere.

That size is significant for both developers and future wetland conservation: More than half of Tennessee’s geographically isolated wetlands are less than one acre in size, according to TDEC.

“Let’s just be clear, too, that this is driven by the financial interest of single individuals to the detriment of the common good,” said Tennessee state Sen. Heidi Campbell, D-Nashville. “It is just crazy to me that we’re actually talking about loosening restrictions at this moment in time.”

Tennessee has lost nearly 60% of its original wetlands, which hold significant economic value because of their ability to moderate extreme weather events. The state’s remaining isolated wetlands have been estimated to be worth $21.5 billion, or nearly $50,000 per acre.

The state spends significant funds each year trying to restore these natural systems, according to Horace Tipton, conservation director of the Tennessee Wildlife Federation.

“Had we just left them in place in the beginning, we wouldn’t have the problems that we do,” Tipton said. “If we craft our wetland policy in the wrong way, it is very likely we’ll find ourselves in that situation all over our state.”

The state will formally take up the issue during the next legislative session.