McEWEN, Tenn. — Tammy Shaw and her granddaughter, Hope Collier, were trying to find an escape path when water started spilling under their doors.

It was Aug. 21, a day Middle Tennessee residents will likely never forget; one that left 20 people dead. Nearby, nearly 21 inches of rain fell, shattering the state’s all-time record of 13.6 inches over 24 hours.

Cars, houses and even Collier herself were swept away by the storm. Both Shaw and Collier survived, but not without trauma.

“We were trapped in there, in that water,” Shaw said in the immediate aftermath of the storm.

“It didn’t even take ten minutes and it was in my house, and then it wasn’t even 15 minutes and it was up to my ceiling,” Collier added.

Tennessee and neighboring Kentucky were hit by the worst of weather extremes in the past year. Before the deadly August downpour that now stands as the largest 24-hour precipitation record in any non-coastal U.S. state, Nashville experienced major flooding that damaged hundreds of homes and businesses, and killed at least six. And in December, tornadoes killed 80 people in Kentucky, the worst death toll from any tornado outbreak in state history.

But there, the similarities end.

As scientists increasingly trace the fingerprints of climate change on extreme weather and national weather experts recommend collecting a lot of localized, ground-level weather data in real time to save lives, Kentucky has built an extensive “mesonet,” while Tennessee leaves local forecasters partly flying blind in the storms.

The Kentucky Climate Center at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green has, over the last 15 years, assembled a network of 76 local weather monitoring stations—the mesonet—and plans to add up to 20 more stations in the next three years.

“The weather service would be lost without the Kentucky Mesonet,” said John Gordon, meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service office in Louisville.

Forecasters like Gordon with the weather service use the stations to help track rainfall rates, wind speed, air pressure, temperature, sunlight and soil moisture to help make their forecasts more precise and to assist in issuing warnings.

Equally important, Gordon said, is knowing when not to issue a warning. “You know, dear God, I don’t want to be the boy who cried wolf,” Gordon said.

Tennessee has no statewide network of localized weather monitors. The radar systems they use are very useful, meteorologists say, but Gordon said they track conditions thousands of feet high and can miss what is happening on the ground. So in a state that’s 432 miles long, bordering North Carolina to the east and Arkansas and Missouri to the west, local forecasters are often left to estimate local weather conditions and storm activity where people are at risk.

“I’m sure we’ve missed quite a few high-wind, high-rain events across the state simply because we don’t have stations in those locations,” said Andrew Joyner, who leads a newly created Tennessee climate office and serves as the state’s official climatologist. One of his goals is to build a Tennessee mesonet with a station in each of the state’s 95 counties.

“It’s not cheap to build these stations and then to manage them,” he said. “But we feel like there’s a critical need for it.”

Billion-dollar disasters on the rise

Fossil fuel emissions and other human activities are producing greenhouse gases that scientists say are disrupting climate and weather.

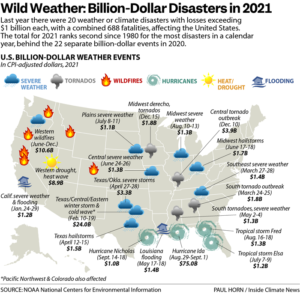

Last summer, in the first installment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report, scientists found that global warming is worsening deadly weather extremes and that every part of the planet is affected. In the United States, the number of billion-dollar weather and climate disasters has been on the rise, even when adjusted for inflation — an annual average of 17 in the last five years, compared to an average of 7.4 per year since 1980. There were 20 billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in 2021, including storms, floods and fires.

In the Southeast, the most recent National Climate Assessment reported cities are experiencing more and longer heat waves. Climate change is also intensifying the hydrologic cycle, worsening droughts and heavy rainfall.

“There is data suggesting that these storms that we are seeing are becoming more frequent and extreme,” said Leah Dundon, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Vanderbilt University and director of the Vanderbilt Climate Change Initiative.

Since 2000, Tennessee has experienced 33 major disaster declarations involving severe storms and flooding, according to a new climate profile of the state from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Among them is the two-day rainfall record for Nashville in May 2010, when 13.6 inches fell, shattering the previous record of 6.7 inches in 1979 and causing catastrophic flooding that killed 18 people in Middle Tennessee. For last year’s nearly 21-inch storm in August, an area of up to 1,000 square miles experienced rainfall totals that would be expected to occur less than once every 1,000 years.

But as bad as the August storm was, it could have been worse, Joyner said.

“This was a largely rural area,” said Joyner. “It was devastating, it was awful, but it could have impacted a much higher population area. You could have moved it 60 miles east and it’d been right in Nashville, and what would that have caused? I mean this same event could really happen anywhere in Tennessee.”

‘A fundamental need’

In all, 35 states have mesonets, according to the American Association of State Climatologists. Those officials typically direct state climate offices and oversee the collection, analysis and distribution of weather data. Mesonets are paid for with a variety of private or public funds. A single monitoring station can cost as much as $29,000, not including the ongoing costs for operation and maintenance.

In a way, mesonets are just another form of adaptation to a changing climate, said Kevin Brinson, director of the Delaware Environmental Monitoring System and chair of the climatologists association’s mesonet committee.

“I would argue that weather data drives so many decisions in our society and our economy,” Brinson said. “It’s a fundamental need.”

The word mesonet comes from the meteorological term, mesoscale, referring to an area of about a 20-mile radius around a location, said Rezaul Mahmood, director of the High Plains Regional Climate Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“The idea is that if we have stations approximately every 20 miles, we should be able to observe weather properly, particularly like when you think of severe weather,” he said.

Most state mesonet systems don’t have weather stations every 20 miles, Mahmood said. But still, mesonets are providing dozens more monitoring stations than what the National Weather Service operates on its own, often at airports.

The first were in Nebraska and the Dakotas in the 1980s, with less frequent reporting and no cell phone networks, Mahmood said. Then Oklahoma developed one in the 1990s with more frequent reporting.

Over time, and with improving computer and communications technology, mesonets now typically report their data every five minutes, he said.

Beyond forecasting, the networks are useful in other ways, said Mahmood, who helped launch and develop the Kentucky Mesonet.

Farmers, he said, use soil temperature and moisture data collected at the stations to make decisions on planting and managing crops. The National Transportation Safety Board once sought localized weather information when investigating a multi-fatality motor vehicle accident in Kentucky, he added. School superintendents use them to help decide whether to declare a snow day, and students use the data to learn about the weather. Utilities track local weather trends when planning for electricity or natural gas demand, and scientists use the data for climate studies, he said.

While the early systems largely served agricultural interests, most now have a significant public safety role, out of necessity, Brinson said.

For example, he said, the network in New York was in large part a response to Superstorm Sandy, which drove a catastrophic storm surge into the New Jersey and New York coastlines in 2012 and ranks as the fourth-most costly U.S. hurricane on record.

“A lot of times states kind of unfortunately have to go through some pretty rough times with weather sometimes before they start to see the value of having a real time network like that available,” Brinson said.

Tracking tornadoes on the ground

The science of climate change and tornadoes remains murky, but there are signs that tornado outbreaks may be shifting from the Great Plains east, to include the Southeast, in what some are calling Dixie Alley.

Gordon, in Louisville, said the Kentucky Mesonet was essential for tracking December’s unusual tornado outbreak and issuing warnings.

A series of storms broke out in Arkansas on the night of Dec. 10 during unseasonably hot and humid conditions, racing across Missouri, Illinois, Tennessee and Kentucky. They produced the nation’s deadliest December tornado outbreak, with at least 90 fatalities, 80 of them in Kentucky. One of the tornadoes cut a path on the ground for more than 165 miles, and was as much as a half-mile wide when it tore through western Kentucky.

“For the tornadoes, we were looking at … real strong pressure rises and falls very close to some of the stations,” Gordon recalled. “You could see some strong wind gusts.”

Once a tornado is on the ground, forecasters use the mesonet to look at whether conditions there are likely to sustain it, stop it or elevate it, he said. Before the Kentucky Mesonet, the nearest weather station could have been many miles away, leaving meteorologists to rely on weather radars that help but do not directly tell forecasters what is happening on the ground.

“The mesonet gives us ground truth,” Gordon said.

That’s also very helpful with rain and flooding, in part because they can tell meteorologists rainfall rates as the rain is falling. “Rainfall rates are everything,” he said. “It’s just literally gold for us.”

On a farm in Warren County

In 2007, the Kentucky Mesonet opened its first station on Western Kentucky University’s 800-acre farm in Warren County. On a recent winter afternoon, Stuart Foster, who created the state’s mesonet during his two-decade career as Kentucky’s state climatologist, explained how it worked.

This station, with 17 sensors, begins underground, with soil probes for moisture and temperature, and rises ten meters to the apex of a tower.

Temperature, relative humidity and wind speed are measured at different heights to reveal temperature inversions that can influence fog formation and air pollution dispersion, and help with daily weather forecasts.

The precipitation gauge looks like abstract art, with a cylindrical base surrounded by metal teeth, called wind baffles, that reduce the wind flow to better catch raindrops. Newly added cameras give visual assistance to forecasters.

“We think of the mesonet here in Kentucky as a statewide infrastructure for environmental monitoring,” said Foster, a retired geography professor at Western Kentucky University.

The Kentucky Mesonet was initially financed through a $3 million federal grant. In 2021, the Kentucky Mesonet received $750,000 from the state’s General Assembly, along with contributions from local sponsors and federal grants.

“It’s just a perfect example of how tax dollars should be spent and how programs should work, where we are very much integrated working towards a common purpose,” Foster said. “In this day and age, it’s kind of refreshing to find something like that.”

‘A big paradigm shift’

In January 2021, Tennessee opened an official but still-unfunded climate office and named Joyner as state climatologist. Building a network is his biggest priority, and he has found support from academic and state institutions, as they look north to Kentucky’s success.

“Everybody’s drooling and jealous of the system they have in Kentucky,” Dundon, the researcher at Vanderbilt University, said.

Joyner is working with state emergency management, environment, agriculture and weather agencies to determine how to pay for stations, where to put them and who will maintain them.

“Meteorologists love to get data and mesonets give data,” said Larry Vannozzi, the meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service office in Nashville.

He said a Tennessee network with a weather station in each county would be a big help tracking storms as they develop and move across the state. “They fill in holes,” Vannozzi said, and “help us to understand what is happening now.”

Joyner still has persuading to do with administrators and politicians, but said he is feeling increasingly hopeful about a Tennessee mesonet.

“It would be a big paradigm shift,” Joyner said.

This report is a collaboration between WPLN News and Inside Climate News, a national nonprofit newsroom covering climate, energy and the environment. James Bruggers covers the Southeast for the Inside Climate News National Environmental Reporting Network.