When Cookeville High School announced plans to cut its International Baccalaureate program earlier this year, the news struck a nerve for Quentin Ding.

“The reality is, a lot of elected officials and a lot of adults make decisions for students,” says Ding, a junior at Cookeville. “We don’t have any say in it.”

The International Baccalaureate, as the name suggests, is a globally-recognized academic program designed to help students become critical and independent thinkers. It’s one of the ways high school students can earn college credit, and the number of Tennessee schools offering the curriculum has been steadily growing over the last decade.

But this year, the cherished program was in jeopardy at two high schools — one in Cookeville and the other in Ooltewah, just east of Chattanooga. Ultimately, only one survived.

In a year marred by controversy over what should be taught in public schools, the rift over IB reopened wounds. Some students felt the program was routinely misunderstood and undervalued. Others took offense to how little they were involved in the decision to discontinue the curriculum.

The state of IB in Tennessee

IB is taught in 159 countries and 1,900 schools in the United States. The nonprofit offers four different academic courses based on grade level, but it’s most commonly recognized for its diploma program for high school juniors and seniors.

In Tennessee, 25 schools have IB status with two in the application process, according to the organization. Robert Kelty, the company’s senior development manager, says what’s impressive about Tennessee is that nearly all of its IB programs are offered in public schools, which is less common in other states.

IB has its strongest presence in the state’s large, urban school districts, like Metro Nashville Public Schools and Shelby County Public Schools.

In Putnam County, Cookeville is the only high school to offer the diploma program, which is partly why students and parents argue it should stay. They say the unique curriculum gives students a competitive edge over other schools.

“The IB program is what sets Cookeville High School out from other schools in the county,” Ding, the high school junior, says. “We have students coming in from other surrounding counties just to be able to take IB classes.”

Kelty says that’s not surprising. “What truly makes the IB so special, whether you’re in rural Tennessee or you’re on Native American lands or you’re in a major metropolis, you are getting access to an internationally recognized education,” he said.

A difference of opinion at Cookeville High

IB is just one of the early post-secondary options in Tennessee. The state also offers the Advanced Placement program, dual enrollment on college campuses and dual credit, which allows students to earn credits at Tennessee universities in high school classrooms.

But Preston McCann, another junior at Cookeville High, says IB is fundamentally different.

“It makes you reflect more on what you’re learning,” McCann says. “For me, it helps me better understand versus here’s what you need to know to take a test.”

IB is generally less exam-based than traditional classes, and in order to earn an IB diploma, students are tasked with writing a 4,000-word final essay on a topic of their choice. Some students say that allows them to be more creative and engaged with their work.

Still, in recent years, the program’s enrollment took a hit, and its stability has been in question. Right now, 89 students are in an IB class in Cookeville. The school year before the pandemic, that number was 143.

“The last five years have been rocky at CHS. We have been through many leadership changes, three different IB coordinators, and COVID shut down our school, making recruitment impossible,” said Emily Chambers, the current IB coordinator.

She added that money to certify teachers has also been a challenge: “I don’t ever really know how much funding we will receive.”

But for some IB students, the real issue has to do with choice and having a say over what they’re learning. The school district ultimately decided to table the matter for now, but promised families will have an opportunity to weigh in once the issue is revisited.

“I fully expect them to try again next year,” Ding says. “I’m also confident in the younger classes that they will put up a fight as well to keep this program around.”

Is IB worth the cost?

The program still has its critics.

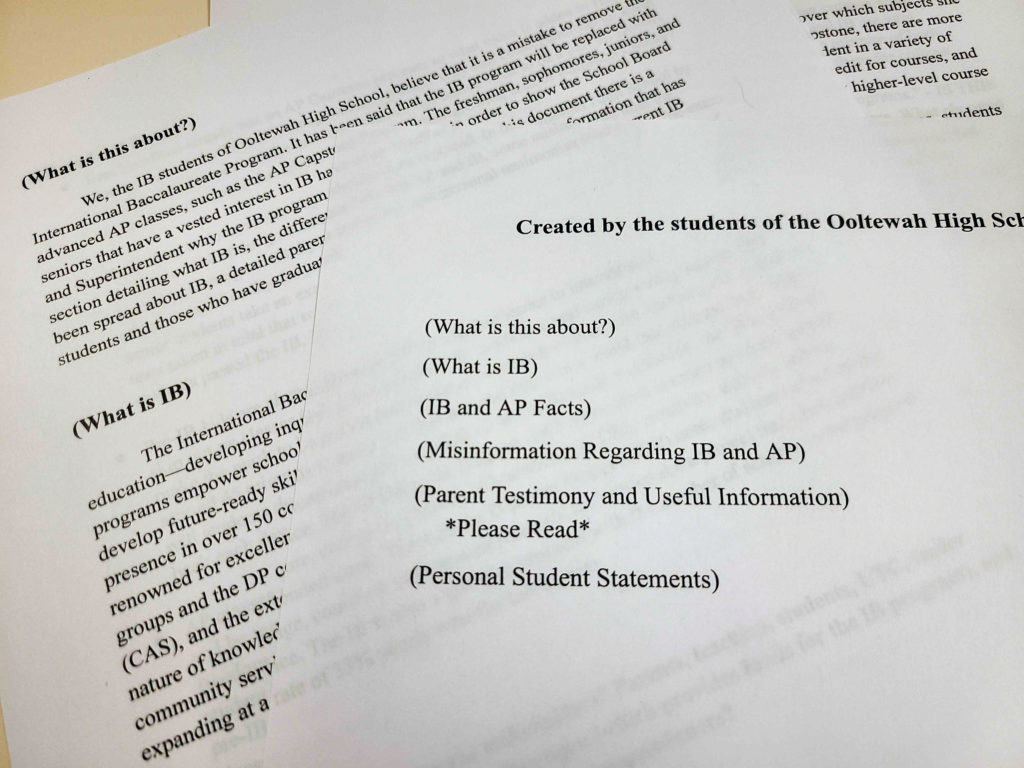

A month after Cookeville’s announcement, Ooltewah High School in eastern Hamilton County revealed its plans to cut the program in February, citing classroom constraints. Currently, 61 juniors and seniors are enrolled in IB courses at Ooltewah, which is roughly a tenth of its upperclassman population.

“Class sizes are extremely small, with the average IB class serving 14 students. While beneficial to those students, it results in other classes serving as many as 35 students,” the district wrote in a press release explaining its decision.

Benjamin Nielsen, a senior at Ooltewah High, says that’s justifiable, but he also believes IB rarely received the support it deserved.

“The issue is that because IB is discouraged and genuinely wasn’t promoted, the numbers were low,” he said.

Nielsen wasn’t familiar with IB before high school. When he asked to learn more about the program in his freshman year, several teachers spoke against enrolling, saying that the coursework is difficult, Nielsen recalls.

But Nielsen is thankful he didn’t listen. IB turned out to better complement his learning style. After enrolling in the courses, Nielsen says he went from being a procrastinator to a student who goes above and beyond the assignment.

Despite pushback, school officials ultimately decided to discontinue the program after the 2022-23 school year. Nielsen still wonders if there could’ve been a better way.

“What if there was an option where IB could have supported standard classes by creating a tutoring program? Or what if we had a better plan to advertise IB? ” He says. “Could we have come up with a solution together?”