This week, city officials offered a rare glimpse into planning for the East Bank development.

The controversial project is massive, expensive and will require decades of work. Metro’s chief development officer, Bob Mendes, met on Monday with the Ad-Hoc East Bank Committee on Monday, and the price tag and the timeline were hot topics.

“The prior administration made a lot of comments about how the East Bank would pay for itself, or was going to be free to the general taxpayer,” Mendes said. “I would describe it as free to the general taxpayer — over a 30-year time horizon — but somebody’s got to pay for a bunch of stuff up front.”

As it stands, the project’s infrastructure costs for the 30-acre initial development zone total $227.4 million. The cost-sharing agreement between Metro, the developer (Boston-based Fallon Company, who beat out seven other bidders in September) and other potential paying parties remains under negotiation.

And there’s a lot to pay for. Under the new Titans Stadium agreement reached last year, Metro is responsible for a $64 million parking garage. There’s also a new sewer pump station costing upwards of $30 million — a need born out of constructing what is essentially a new neighborhood from scratch. (The Titans will contribute 20% of the pump costs, to account for the waste generated by the stadium).

Housing also featured heavily in Monday’s meeting. Right now, the plan looks to create 1,550 new residential units across at least five residential buildings. 695 of these will be affordable housing units.

There’s also the new Tennessee Performing Arts Center, which looks to have a new riverfront home on the East Bank, pending a tentative agreement reached with TPAC.

These updates, provided by Mendes, are still subject to change.

“We are doing something that, at least in my time in Metro government, I haven’t seen done before,” Mendes said. “That is, we’re giving a snapshot in time in the middle of a negotiation.”

The master development agreement is expected to hit the Metro Council by early March. Before then, Councilmembers Clay Capp and Sean Parker have scheduled a town hall meeting — open to the public — for the last day of January.

Some community members are already involved in the East Bank conversation.

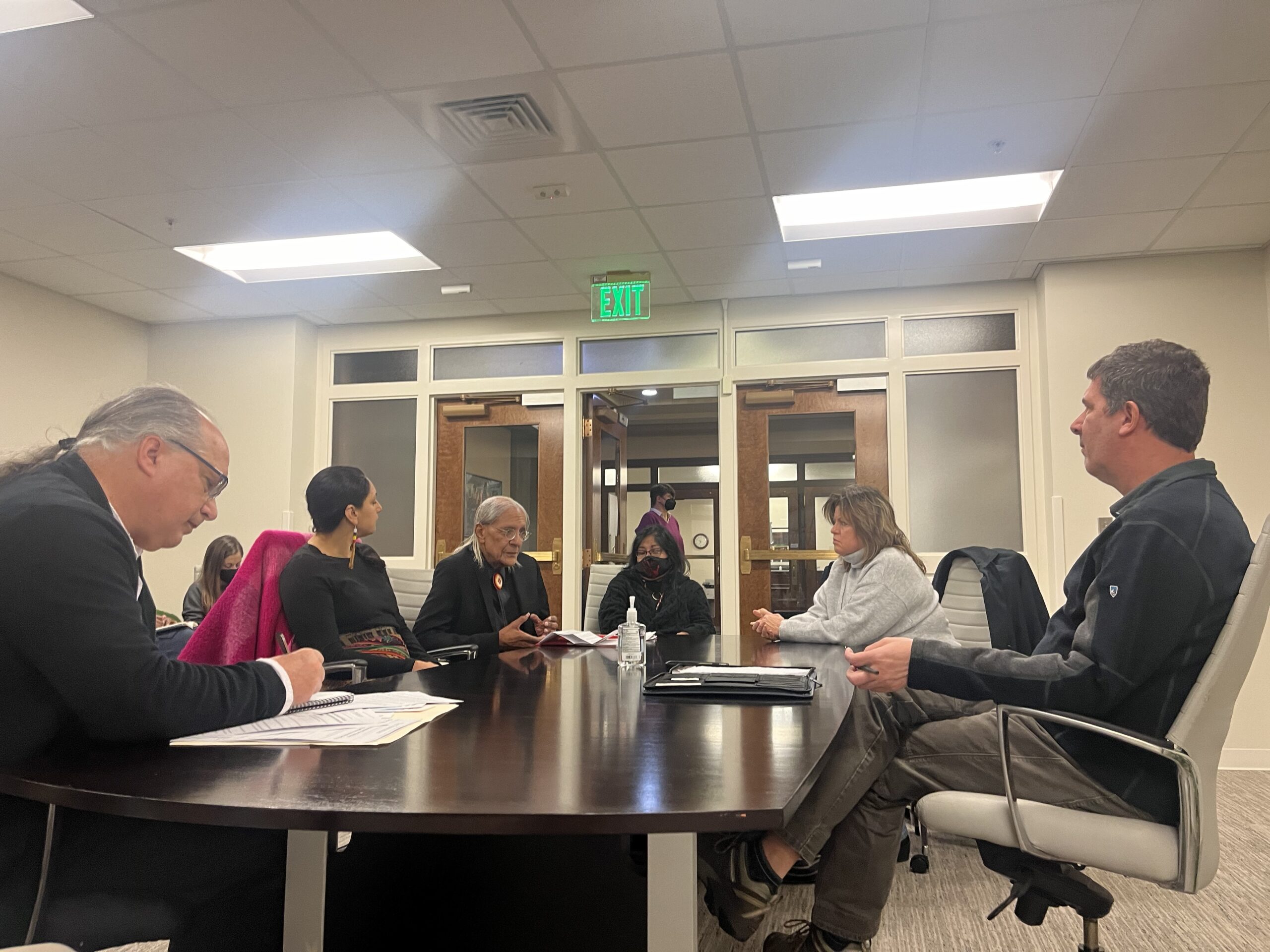

Earlier this month, Indigenous leaders met with Mendes to discuss their concerns around protecting what was once home to a sprawling community.

Cynthia Abrams WPLN News

Cynthia Abrams WPLN NewsLocal Indigenous community members meet with Metro Chief Development Officer, Bob Mendes, to discuss the future of the East Bank development on Jan. 12, 2024.

“All of downtown Nashville sits on top of an ancient Native American city,” Albert Bender, a local Indigenous leader, said. “What we want to see is recognition and preservation, as it were, of ancient Native American history, so that the ancient indigenous history of this area is not erased.”

Attendees asked that Metro craft an Advisory Council composed of Indigenous members, non-native members and Metro officials to work towards preservation of the land and Indigenous history.

This preservation could look like plaques, educational opportunities, a written land acknowledgement or a conservation easement between Metro, the Native American Indian Association of Tennessee and the Tennessee Ancient Sites Conservancy on five acres of Metro owned land. (A conservation easement is a voluntary legal agreement that limits how land can be developed, used or subdivided.)

The group asked for another meeting to further discuss their requests. It has yet to be scheduled.

Mendes said he would take these requests to the mayor. There is currently a study intended to identify archaeological sites in the project’s potential impact area planned for the site.