Students at the University of Memphis class of 2011 sat in a large auditorium as their loved ones celebrated this chapter of their lives. But as the graduates walked across the stage in caps and gowns, one name wasn’t called.

Jamel Turner, who is Black and from Memphis, was purged from the college the prior year because of financial troubles. He had a 3.8 GPA and big aspirations for law school.

“I wanted to be a representative,” he says. “I was going to be, at that time, the first in my family to graduate.”

Turner was well on his way to that goal until he agreed to help out a family member. The decision led to problems with his financial aid.

“I was doing my own FAFSA, handling my own, and my mom was like, ‘The tax credit would help me out a lot if you would let me put you on my taxes, and I would have to do your FAFSA,'” he explains.

Turner let his mom claim him as a dependent so she could have a better tax return. But Turner says she didn’t follow through with completing his financial aid application and he needed the money for housing and tuition.

“Because I was staying on campus, I owed about $2,300,” he says. “The school wouldn’t move forward with me on anything until I paid the money back.”

At the time, Turner says, he was making $1,000 per month. Getting kicked out of college because he couldn’t pay resulted in a downward spiral. He lost his housing and started sleeping in his car. He essentially gave up on his future. That was in 2010, and he still hasn’t processed the devastation caused by his mom not holding up her end of the deal.

“I told my mom the other day, because I’m ready to get over it, I’m about to start therapy,” he says. “I was just telling her, you know, I lived in the city. I went to school in the city. I moved myself in and out of my dorm by myself every time.’”

Courtesy Tennessee Higher Education Commission

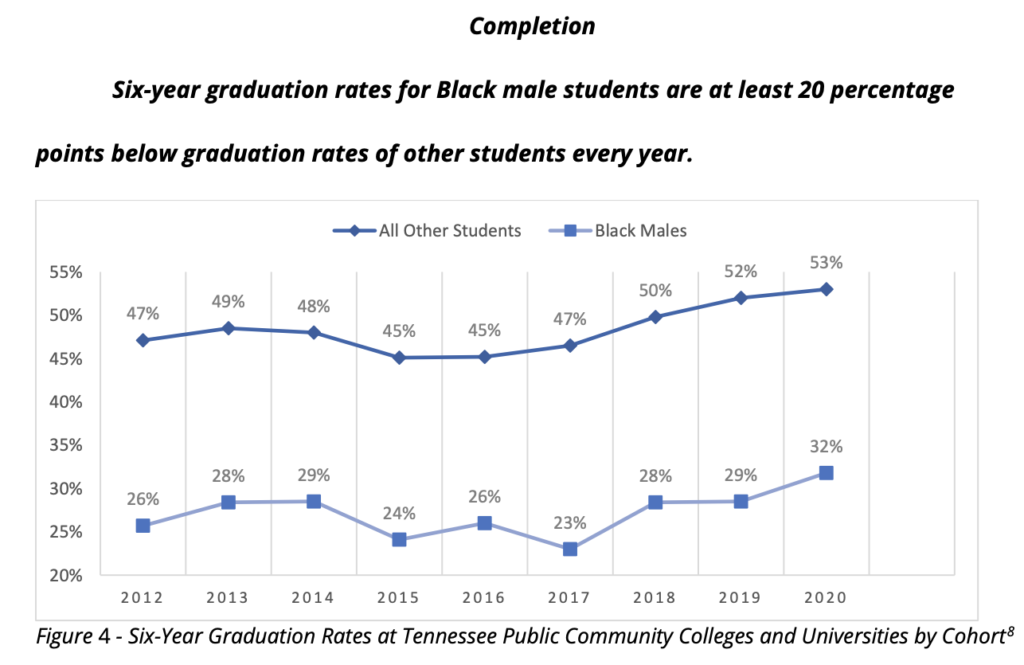

Courtesy Tennessee Higher Education Commission A report from Tennessee’s Black Male Success Initiative shows the six-year graduation rate for students at public community colleges and universities.

As Tennessee higher education leaders continue a push to graduate more students from college, the attainment gap for Black males has remained the same. The six-year graduation rate for those students is at least 20 percentage points below the rates of their peers each year, according to the Tennessee Higher Education Commission.

Last year, the state developed the Black Male Success Initiative to address the issue. Taskforce member Shawn Boyd says, while improvements won’t happen overnight, he’s hopeful the initiative will spark change.

“Even to get this many people in one space to say, ‘Hey, we have a problem,’ because if I think back five years ago, we didn’t have this.”

Boyd says the group is starting to hold listening tours at college campuses across Tennessee to hear from Black males about their experiences in higher education.

“We have to really reimagine college for our students and not just say, ‘Hey, go to college,’ like what was done to me,” Boyd says.

A recent report from the state’s initiative pointed to several barriers preventing Black males from getting a degree: not feeling like they belong on college campuses, being stereotyped as at-risk and having unmet financial needs.

But those barriers also affect other groups of students, like Latinos, Black women and some white people — all of whom are graduating from public colleges at higher rates than Black males.

“I think that us, as African Americans, have too much pride as well,” says Darrell Miller, a coach at Persist Nashville, a nonprofit that helps Nashville students stay on track to earn college degrees. “What do we look like going to sit down and speaking with somebody who doesn’t know us from Adam and Eve, and express how we feel or have been feeling in the past? Are they really going to listen to us?”

Damon Mitchell WPLN News

Damon Mitchell WPLN NewsDarrell Miller stands inside a room at a Nashville high school.

Miller grew up in North Nashville and knows firsthand the challenges of young Black males. He graduated from Tennessee State University in 2005, where the latest graduation rate for Black males sits at 19%. He now works with hundreds of high schoolers and college students. Many of them are Black males who face mental health disparities that their peers don’t have — which makes it harder for them to focus on completing college.

Another challenge, Miller says, is Black males aren’t collectively exposed to high-paying career options, like being an astronaut or dean of a university. That can make college seem like it’s not worth completing. It also makes side hustles look like a better option.

“I have students I speak to all the time,” Miller says. “A lot of them just straight up tell me, ‘I don’t have to go to school to get money at this point in 2022.’”

Many Black males, he adds, see college as a bad investment if the result is a low-paying job. There’s truth to that. Having a degree is not always a wealth generator for Black people.

In 2014, a study by Young Invincibles found that Black males with some college had the same chance of getting a job as a white male who dropped out of high school. Miller says a lot of people have desires to become entrepreneurs and create their own wealth instead of hoping that someone hires them.

“We don’t want to be stuck with debt at 18 to 21 years old, and end up not using that degree because we can’t get hired because of a lack of experience,” Miller says.

Still, for Black males who do want to get a degree, Jamel Turner says there needs to be programs in place to provide financial and emotional support.

“I think that we should put therapy in these schools,” he says. “I think that we should get these boys talking.”

Unaddressed traumas, Turner says, cause many young Black males to get off track. Having access to therapy while in college could be the key for them to complete a degree.

“I think that’s where we lose out, most of us, because a lot of guys come in and they drop out or are on drugs because of their home life, before they even get a chance to be college students.”