Scraps of paper are piled up on a desk with words scribbled on them.

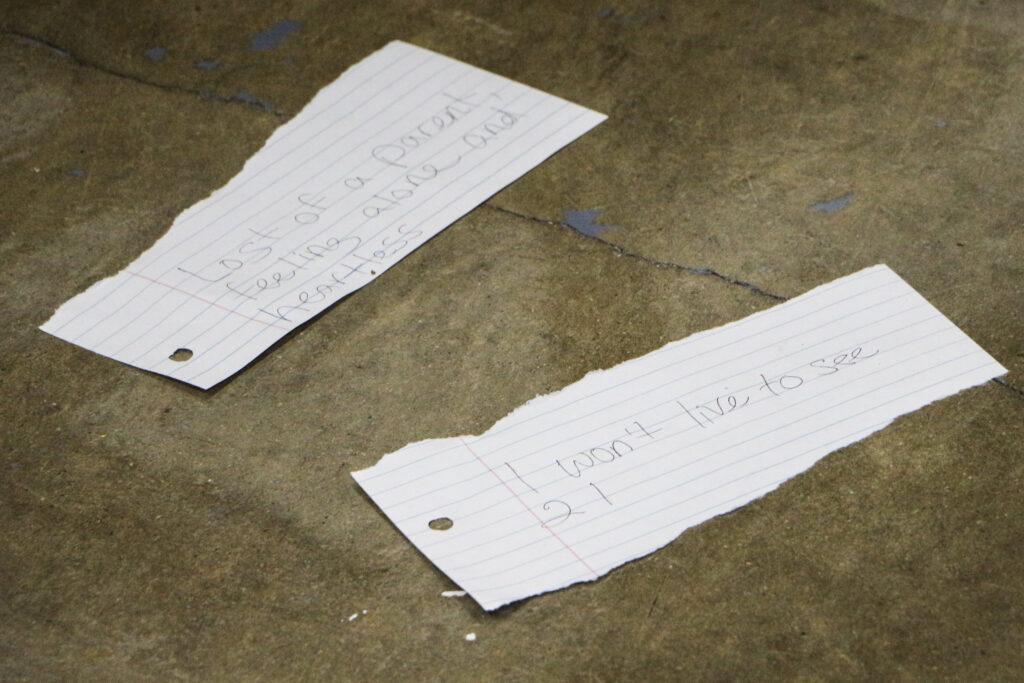

One says “gangster.” Another? “I won’t live to see 21.”

A group of young men are gathered in a circle around David Richardson. He wears round, gold rimmed glasses and has quiet command over the group.

“We’re going to look at some, I’m assuming, bad labels,” he says, instructing the guys to reach in and grab a piece of paper. “I got ‘felon’ and ‘You will never be anything in life.’ ”

They each go around reading from the slips — “disappointing,” “worthless,” “thug,” “lost cause.”

These labels are the ways these men feel society sees them. And they’re familiar with being labeled – the words “Tennessee Department of Correction” is printed across the back of their identical powder blue shirts.

Paige Pfleger WPLN News

Paige Pfleger WPLN NewsThe young men in the mentorship program wrote down labels they feel have been put on them.

“So all y’all know my struggles,” Richardson says, “and I want to create the space that if you feel comfortable to sell some of your struggles.”

Across the table, 26-year-old Tyrin Cherry says those labels are what you make of them.

“We’re labeled felons,” Cherry says. “But look what we’re doing. We’re actually trying to change and all that. … It’s just what you make of it.”

Cherry is up for parole next year. But Richardson is serving a life sentence. Their conversation is part of a new mentorship program inside the Turney Center that pairs lifers like Richardson with first timers like Cherry.

People serving life sentences often have a lot of sway over the culture of a prison – they remain, while others cycle in and out. At Turney Center Industrial Complex, a prison about an hour southwest of Nashville, men with life sentences are trying to use that influence for good.

“The older guys have been in prison so long, there’s pitfalls that they can help them to not fall in,” says Gildor Simplice, a prison counselor.

‘The world at their fingertips’

Simplice helped connect these two groups, who normally wouldn’t have much contact with each other.

“Usually a lot of them come very young and they’re like, ‘You know, if I had a big brother, prison life would have been a little easier for me,’ ” Simplice says. “And so we started working on how to start one. And here we are.”

David Richardson wanted to be part of this program — he knows firsthand how important that type of guidance can be when a young person comes to prison.

Paige Pfleger WPLN News

Paige Pfleger WPLN NewsDavid Richardson serves as a mentor to younger incarcerated people at the Turney Center Industrial Complex.

He was 20 years old when he was sentenced to life. And he remembers there was pressure to join gangs and continue to get into trouble. But there were older guys who helped him find another way.

“So I’m inspired by the people that were there for me,” he says. “And I’m hoping to be one of those persons for these little brothers that we got.”

To Richardson, being a mentor and offering guidance means being open and vulnerable with the younger guys about how he ended up with a life sentence for murder.

“I didn’t have any prospects of going to college, of doing anything with my life,” Richardson says. “I knew that this was where I was coming. And it’s so unfortunate that I think a lot of the young guys that we deal with and a lot of them that were in here today, you know, have this same expectation.”

‘I never want to come back’

Richardson says there is something incredibly special about being able to build connections with these younger guys now.

It’s an inflection point — they have a chance when they leave prison to change their trajectory, to start over, to do things differently.

“Some of these young guys might be far more brilliant than me,” he says. “They are more creative than me. They are. They got the world at their fingertips, and I just want to help them see that.”

Paige Pfleger WPLN News

Paige Pfleger WPLN NewsThe Turney Center Industrial Complex is a prison about an hour from Nashville in Only.

Richardson says it’s hard to see himself as someone to look up to. He’s made mistakes, and he’s only 32 years old.

But his openness about his experiences is why younger guys like Tyrin Cherry admire him so much.

“I didn’t have a father growing up, so he’s someone I can look up to,” Cherry says. “He’s not much older than me, so he’s like a big brother, but he’s definitely someone who I could model my entire being around.”

Cherry says this group, and having a role model like Richardson, is kind of like therapy to him. For the first time, he isn’t afraid to say what he hopes for himself, and for his future.

“I don’t want to be labeled another statistic who just comes back to jail and keeps coming back to jail, because next time it might be for a life sentence,” he says. “So I just got in here and changed my whole thinking and just I never want to come back.”

The group is setting him on a new path, he says. And that path does not lead back to prison.