Before Mayor Freddie O’Connell unveiled the details of his transit plan, a big question loomed: Would he pursue light rail?

The answer was, ultimately, no. Light rail lost big back in 2018 when Nashville pursued dedicated transit funding via referendum. So, O’Connell went with a different kind of high-capacity transit: bus rapid transit.

BRT can include things like traffic lanes only for buses, signals that go green to keep them moving, separate branding to differentiate from other city buses, off-board or pre-paid fare collection, real-time passenger information, and level boarding through high-platform stations or low-floor buses.

Those kinds of features would fundamentally change the way that Nashville’s public transit system works.

While BRT can’t carry quite as many people as trains, WeGo’s director Steve Bland said it has its perks: It’s much cheaper to build, and it’s easier to integrate into existing bus routes.

But, bus rapid transit varies between systems in different cities.

“There is pretty significant disagreement or discussion among transit professionals about what BRT is and what BRT isn’t,” Bland said. For example, some systems include dedicated lanes while some don’t, or some have traffic signal priority while others don’t.

And, as evidenced by O’Connell’s proposal, it can also vary within a single system.

Nashville’s proposal

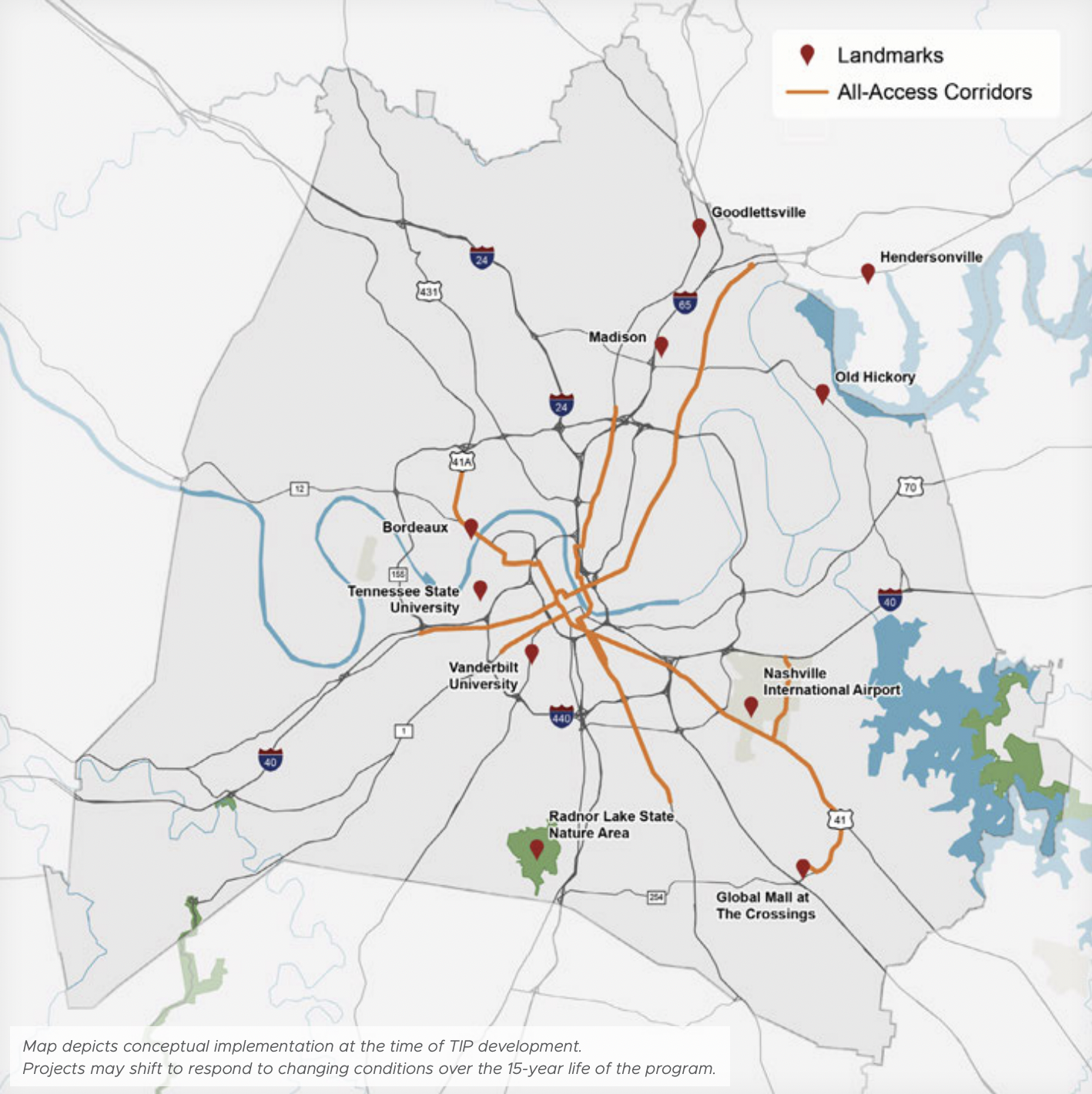

BRT is a cornerstone of O’Connell’s 94-page plan. Ten roadways — Murfreesboro Pike, Gallatin Pike, Nolensville Pike, Dickerson Pike, Charlotte Pike, Clarksville Pike, West End corridor plus various areas of downtown — have been identified as “All-Access Corridors,” meaning they would receive upgrades like more sidewalks and improved signals in addition to a high-frequency bus line.

BRT is a cornerstone of O’Connell’s 94-page plan. Ten roadways — Murfreesboro Pike, Gallatin Pike, Nolensville Pike, Dickerson Pike, Charlotte Pike, Clarksville Pike, West End corridor plus various areas of downtown — have been identified as “All-Access Corridors,” meaning they would receive upgrades like more sidewalks and improved signals in addition to a high-frequency bus line.

At least four of these corridors — Dickerson, Gallatin, Murfreesboro and Nolensville Pike — are being eyed for dedicated lanes in some places. All-Access Corridors are the highest-cost element of the entire transit plan.

Bland said that, ultimately, the goal is to establish reliability — which can mean different things in different areas.

“In this segment of, say, Murfreesboro Pike, we really need dedicated lanes or queue jumps because traffic is complex and unpredictable. And another section where it’s relatively reliable or generally moving well, maybe operating in general traffic is fine or just applying technologies like queue jumps at congested intersections,” Bland said. “It’s really about — can you deliver an upgraded level of service?”

This isn’t the first time Nashville has tried to introduce BRT. While light rail was heavily emphasized in the 2018 plan, bus rapid transit was also incorporated. And, before that, leaders had proposed a dedicated lane down West End, known as “the Amp.”

The Amp proposal was thwarted amid major opposition. When the plan died, the federal funding that Nashville had received for it was redirected to a different city.

“You can ride the Amp, but you have to go to Indianapolis to do it,” Bland said.

Looking to other cities

Through that rerouted federal funding — plus a referendum approving an income tax increase — Indianapolis built 13-miles of BRT known as the “Red Line.” The city will launch a new “Purple” line this month; and a third “Blue” line is in the works for 2027.

Before those projects, Carrie Black, a spokesperson for IndyGo, the city’s transit agency, said many of those streets were a mess.

“We’re talking pitted roads and giant potholes that could swallow a car, terrible drainage, so that after a rainy day you have lots of ponding and pooling, lack of sidewalks, lack of ADA curb ramps,” Black said. “And now, if you drive down the same corridor, it’s night and day. It is transformational.”

And it’s not just roads. Black points to boosted economic development along the BRT lines.

“Businesses, those who are providing jobs, affordable housing developers, all recognize the importance of setting up alongside a bus rapid transit line,” Black said.

Population-wise, Indianapolis is a larger city than Nashville. But, cities that are just a fraction of Nashville’s size also have BRT — and have been sharing similar takeaways with Metro leaders.

Take Richmond, Virginia and its 7-mile BRT system. The city built up its mobility network while launching its BRT line, according to Julie Timm, a transit planner who led Richmond’s transit agency for three years.

“It’s been so successful,” Timm said during a virtual gathering for transit leaders in Southeastern cities. “Now in 2023, 2024, we have a much broader acceptance of transit overall — not just the BRT — but overall acceptance of transit.” Timm also oversaw Nashville’s transit system before moving to Richmond.

Leaders in both Indianapolis and Richmond have a shared message for Nashville and its pursuit of BRT.

“Whatever you do, make sure you are clear in your communication, even the bad stuff that you don’t want to say. Keep it real,” Timm said.

Timm and Black also said challenges are inevitable. Building BRT, while cheaper than light-rail, still costs millions per mile. And, building dedicated lanes would be very disruptive.

So, it will be up to Nashville’s voters: Is the disruption worth the transformation?

Davidson County voters will answer that question on Nov. 5. The transit referendum will ask voters to approve a half-cent sales tax increase to fund a major transit overhaul. In addition to the proposed bus rapid transit, this would include things like new sidewalks, updated signals, a dozen new transit centers and more.