The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation has mapped polluted waterways across the state.

Tennessee boasts about 60,000 miles of streams and rivers, along with 29 reservoir lakes. The state agency has been monitoring their water quality for decades and periodically releases new data.

This year, about 19,000 miles of waterways are considered “impaired” with at least one form of pollution or an alteration to the flow of water.

“This information is incredibly helpful for river managers to help us identify sources of pollution and our efforts to reduce pollution and improve water quality,” said Ryan Jackwood, the science director of the nonprofit Harpeth Conservancy.

One of the most common types of pollution is habitat degradation, which the agency defines as “the physical modification of a stream or river which often results in a loss of habitat.” Others include pathogens like E. coli, soil erosion from activities like agriculture and construction, and nutrients, such as farm runoff from fertilizers or pesticides.

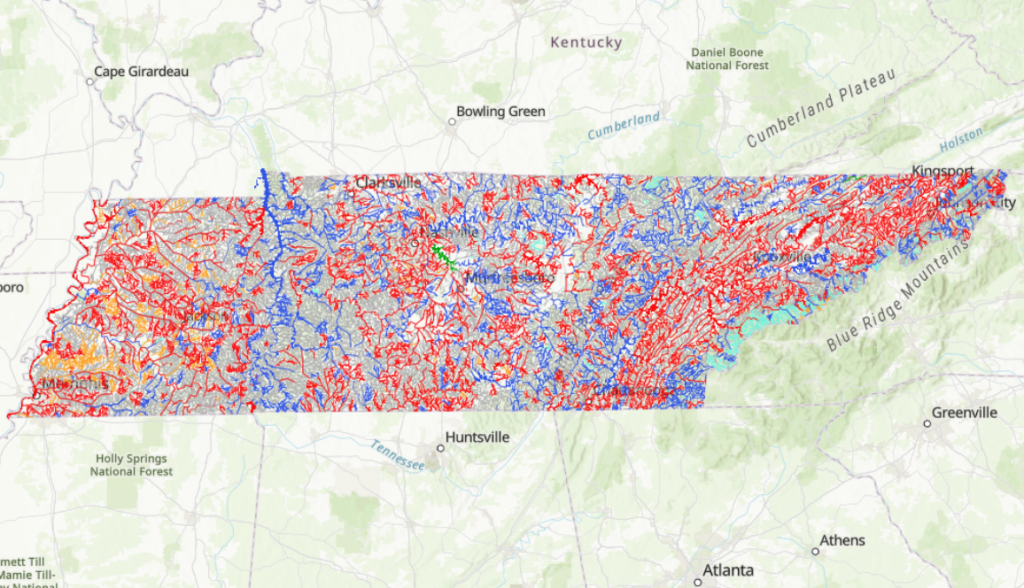

Courtesy Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation

Courtesy Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation mapped about 19,000 miles of “impaired” streams and rivers. Blue represents healthy waterways while red represents impaired streams. Green represents “threatened” waters, which are ones likely to become impaired in the near future. The green portion of the map represents J. Percy Priest Lake and parts of the Stones River.

The agency prioritizes the monitoring of streams that have a history of contamination or likely have new contamination, along with streams that have not been assessed in recent years. TDEC drafts and then posts the information in a list each reporting cycle, according to watershed manager Rich Cochran.

“A list is a snapshot in time,” Cochran said during a public hearing on Wednesday.

Data on the latest draft of the impaired waterways list can be assessed on TDEC’s water notices webpage. Citizens can submit feedback through Feb. 13. More information can be found under “Public Participation Opportunities.”

Cochran encouraged participation, emphasizing that water quality monitoring is an ongoing process.

“If we have new information on data that comes in that needs to be used as part of the regulatory process, those data would trump what was in the most recent assessment,” he said.

Citizens, officials want TDEC to look at Middle Point Landfill

This year, some folks want TDEC to consider independent water samples taken in and near Middle Point Landfill, the state’s largest landfill by volume. It sits right next to the Stones River, which flows into J. Percy Priest Lake and eventually into the Cumberland River.

The agency identified the lake and the segments of the Stones River leading into it as “threatened,” which means the waterways could become impaired in the near future.

The reason people are concerned about Middle Point is leachate, the liquid leftovers after water drains through garbage in a landfill. In 2022, the city sent samples of Middle Point Landfill’s leachate to the national testing lab ALS Environmental. Samples revealed high levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly called PFAS or “forever chemicals.”

“We need to make sure that state law is being followed,” Murfreesboro Mayor Shane McFarland told WPLN. “I feel confident that they will do that.”

Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, or PFOS, was at 15,000 parts per trillion (ppt), and perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, was at 17,000 ppt. Another sample of raw leachate contained much higher PFOA levels of 380,000 ppt.

During the hearing Wednesday, Cochran, the watershed manager, mentioned that he was aware of the samples and would be looking into the issue. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency set its first national limit for drinking water of 4 ppt on six types of PFAS, including PFOA, in 2024 under the Biden administration. But TDEC is not required to monitor for PFAS in streams or rivers for its “impaired waterways” list, also called a 303(d) list. The agency is currently sampling some potential sources of the pollutant into streams that provide drinking water.

Middle Point Landfill treats its leachate but does not have a system designed to remove PFAS, according to attorneys representing Murfreesboro in litigation with the landfill. Samples of treated leachate in 2023 and 2024 revealed PFOA levels of 7,900 ppt and 3,400 ppt, respectively. A representative for the landfill said Middle Point does not produce PFAS but is rather a “passive receiver of material containing PFAS.”

Treated leachate flows into Murfreesboro’s wastewater treatment plant, which is also not designed to remove the PFAS before the effluent is released into the Stones River.

Karst geology around the landfill poses additional concerns, as polluted water can travel through the underground terrain of cracked limestone and into groundwater or local streams and rivers. The landfill is more than 30 years old, so the liner holding in the trash could have degraded in spots over time.