The coronavirus doesn’t discriminate. But some physicians say the public health response is already showing familiar patterns of racial and economic bias.

Meharry Medical College is staffing one of the three city-run, drive-through testing centers in Nashville. All are in predominantly minority communities, and all were delayed in opening by more than two weeks because they lacked the necessary testing equipment and protective gear.

“There’s no doubt that some institutions have the resources and clout to maybe get these materials faster and easier,” says Dr. James Hildreth, president of Meharry and an infectious disease specialist.

His college is in the heart of the historically black community of Nashville, where there were no screening centers until this week. Vanderbilt University Medical Center has done most of the testing in the region at its walk-in clinics, which tend to be in more affluent areas like Belle Meade, Brentwood and Franklin.

Hildreth sees the distribution of testing sites as proof of a disparity in access to medical care that has long persisted. He says he’s seen no overt bias.

But if anyone should be prioritized, Hildreth says it’s minority communities, where people already have more risk factors for complications from the coronavirus — like diabetes and lung disease.

“We cannot afford to not have the resources to be distributed where they need to be,” he says. “Otherwise, the virus will do great harm in some communities and less in others.”

‘A Crisis Within A Crisis’

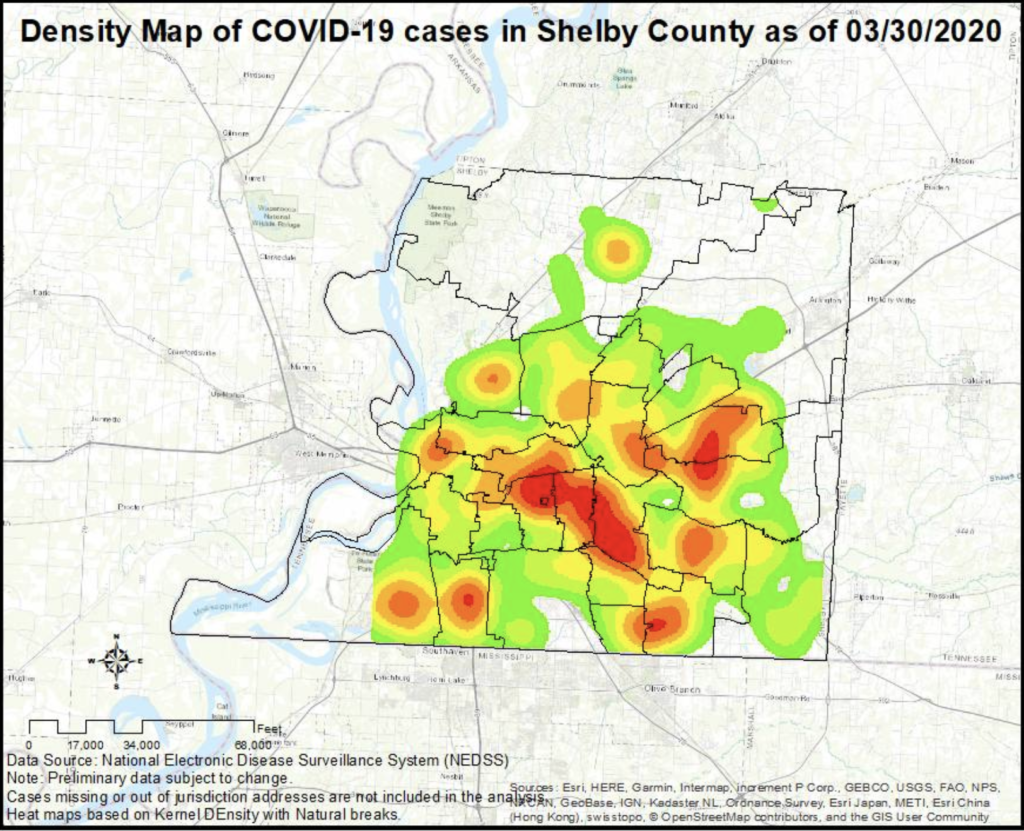

In Memphis, a heat map on the Shelby County health department’s website shows where coronavirus testing is taking place. It reveals the most screening is happening in the predominantly white and well-off suburbs, not the majority black urban neighborhoods.

The Rev. Earle Fisher has been warning his African-American congregation in Memphis that the response to the pandemic may fall along the city’s usual divides.

“I pray I’m wrong,” Fisher says. “I think we’re about to witness an inequitable distribution of the medical resources too.”

Around the nation, there are already pockets of concentrated disparity. In Milwaukee, black people made up all of the city’s first eight fatalities. Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers says he wants to know why black communities seem to be hit so hard.

“It’s a crisis within a crisis,” he said in a video statement.

Nationwide, it’s difficult to know how minority populations are faring because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention isn’t reporting any data on race.

Dr. Georges Benjamin of the American Public Health Association has been pushing the CDC to start monitoring race and income in the response to COVID-19.

“We want people to collect the data in an organized, professional, scientific manner and show who’s getting it and who’s not getting it,” Benjamin says. “Recognize that we very well may see these health inequities.”

The Subjectivity Of Symptoms

Until he’s convinced otherwise, Benjamin says he assumes the usual disparities are at play.

“Experience has taught all of us that if you’re poor, if you’re of color, you’re going to get services second,” he says.

Even for those black patients who are symptomatic, it appears doctors are less likely to refer them for testing.

Boston-based Rubix Life Sciences analyzed recent billing information in several states. The bio-tech data firm researches outcomes for minority communities. It found a black patient with a cough and fever was far less likely to be given one of the COVID tests that have been so scarce.

The subjectivity of coronavirus symptoms is what worries Dr. Ebony Hilton most. She’s an anesthesiologist at the University of Virginia Medical Center who has been raising concerns.

“The person comes in, they’re complaining of chest pain, they’re complaining of shortness of breath, they have a cough, I can’t quantify that,” she says.

She sees problems across the board, from how social media is being used as a primary way of educating the public to how quickly drive-thru testing has expanded. Social media requires an internet connection. Drive-thru testing requires a car.

“If you don’t get a test, if you die, you’re not going to be listed as dying from COVID, you’re just going to be dead,” Hilton says, adding that the country can’t afford to overlook race, even during a swiftly moving pandemic.