As in most of the country, seniors of color in Davidson County are lagging in COVID-19 vaccinations. More than a third of eligible white residents have gotten their first shot, compared with a quarter of Hispanic residents and less than one-fifth of Black Nashvillians.

Targeted vaccinations through nonprofit clinics have begun, and will make up some ground. But it’s slow work, in part because outside factors like transportation are so often barriers.

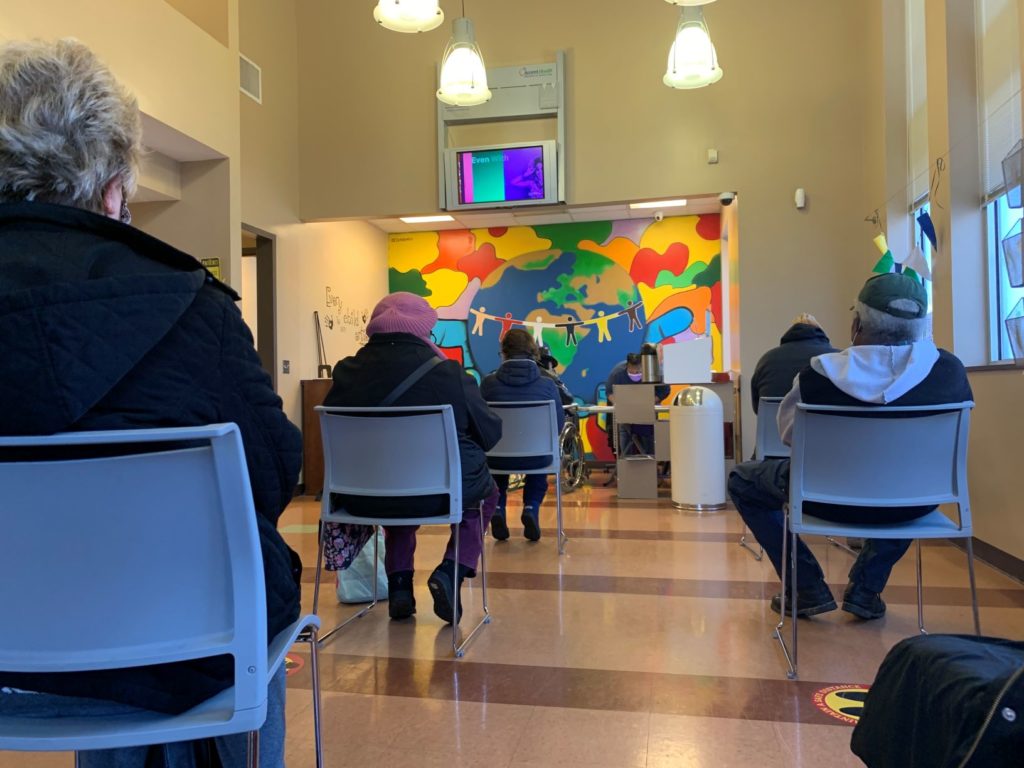

At a clinic late last week in the Napier homes of South Nashville run by Neighborhood Health, 74-year-old Mary Barnett is watching the clock.

“Is my time up, baby?” she says.

She has to wait her 15 minutes after getting the COVID vaccine to monitor for an allergic reaction. But her ride is waiting. Her nephew needs to get to work for his job at UPS.

“Uber,” she jokingly says to him over the phone, “I’m ready. Come on.”

Last week, Neighborhood Health started receiving its first COVID vaccine doses and reaching out to groups that live in public housing, like Barnett. Aside from logistical challenges, she says many of her neighbors are skeptical.

“I tell them about taking it, they say, ‘Oh no, I’m not going to take it.’ I say what’s the reasoning?”

Part of Barnett’s motivation is a sister with kidney disease who died of COVID last July. Her brother convinced her the vaccine was worth any risk.

“You either die with it, or die without it,” she says he told her. “So if the shot helps, take the shot.”

Same story, next chapter

People of color have made up a disproportionate share of the cases and deaths from COVID in Nashville. And the same factors at play with those trends are also affecting the vaccine rollout.

Rose Marie Becerra received an invitation to receive the vaccine through Conexión Américas. She’s a U.S. citizen originally from Colombia. But she’s concerned about those without legal immigration status.

“The people who don’t have documents here are nervous about what could happen,” she says, adding that they feel like giving any of their personal information could result in tracking them down.

State officials say citizenship is not required to get a vaccine, but Becerra says those in that position will need assurance by someone they trust.

Metro Health officials first announced the disparity figures for seniors late last month and say they’re focused on closing the racial and ethnic gaps in vaccinations. In one week, they did show some improvement, says Dr. Alex Jahangir, the chair of the city’s coronavirus task force.

“This is top of mind, I can tell you, for me,” he says, vowing to be “honest with the data.”

But Neighborhood Health CEO Brian Haile says his organization can’t do it alone and will need help from the major health systems that have been vaccinating patients for more than a month.

“We know what’s required in terms of the labor-intensive effort to focus on and vaccinate the populations at the highest risk,” he says. “All of us are going to have to roll up our sleeves and do this kind of work, and I think we will. And I think we are. We’ll just have to bring more of it to scale.”