Christine Williams is afraid that her son will not survive his 12-year prison sentence. He’s one of the 6,300 Tennessee prisoners who tested positive for COVID-19 last year, and his breathing was strained for days.

Now, she says the 33-year-old is sick again and has struggled to get the medical treatment he needs.

“As a mother, I feel helpless,” Williams says. “I mean, I’ve had sleepless nights. I’ve just, I’ve been depressed, I’ve been sick myself. And it’s all because of emotions and feelings and the anxious that you feel because there’s nothing I can do.”

Courtesy Christine Williams

Courtesy Christine Williams Christine Williams says images of her son with lesions all over his body hardly resembled this older photo of him.

Prison deaths in Tennessee increased by nearly 60% in 2020, compared to the prior year. COVID-19 directly accounted for about half.

But experts and prisoners’ loved ones, like Williams, worry conditions brought on by the pandemic could lead to even more deaths this year.

Williams says she’s used to her son’s minor gripes, like about prison food. Those, she says, go “in one ear and out the other.”

But when someone sent her photos of her son covered in swollen sores — on his head, his hands, his feet — she knew these concerns were serious. She even got in touch with the state’s associate director of prison health, according to screenshots of text messages (TDOC says it cannot comment on an individual’s medical treatment).

“When the pictures came to my phone, and I viewed those pictures, I got down on my knees and cried for an hour and prayed,” Williams says. “And when I got up off my knees, I said, ‘Jesus, find me someone that I can talk to to help get my son help, because he’s gonna die.’ ”

‘These systems are broken’

Since the start of the pandemic, WPLN News has interviewed more than 30 people who fear their loved ones are not getting the medical care they need. Some said their relatives were waiting on treatment for cancers or pre-existing conditions like high blood pressure. Others worried about access to masks and cleaning supplies or the cost of medication in the prison commissary. Many dreaded that their loved ones would succumb to the coronavirus.

COVID-19 has claimed the lives of at least 41 Tennessee prisoners, and sickened thousands more. Nationwide, more than 2,300 prisoners have died, according to the Marshall Project. But there’s also concern about a ripple effect: that pandemic conditions are exacerbating pre-existing weaknesses in prison health systems.

“What I have seen as I’ve reviewed thousands of sick call records and medical records of people is that these systems are broken. That they didn’t work before COVID,” says Dr. Homer Venters, former chief medical director of the New York City jail system. He’s a leading expert on correctional health and has inspected about two dozen jails, prisons and immigration detention centers during the pandemic.

Venters says COVID-19 has slowed many facilities’ response times for routine care, and that it has limited treatment of chronic conditions, like diabetes and asthma.

“These are cancers that are getting worse, these are metabolic problems, these are, you know, surgeries that have been delayed … even the most serious of which have been identified by facility health staff,” he says. “But it’s been very difficult to get access to specialty care outside of facilities.”

Plus, Venters says the pandemic has restricted behavioral health services and addiction treatment — at a time when anxiety is running high.

The Tennessee Department of Correction says the only interruptions to its programs have come from providers occasionally getting sick. But accidental deaths, which include overdoses and other unintentional fatalities, at least doubled in 2020. The manner of death had not yet been determined in about 60 cases, as of Jan. 5.

“Drugs are everywhere. Tobacco is everywhere. And, I mean, they know it,” says Shannon Young.

Her husband is incarcerated at the South Central Correctional Facility, where nearly 80% of prisoners have caught the coronavirus.

‘That’s their responsibility’

Young says her husband struggles with drug addiction. He’s told her that the availability of drugs has grown during the pandemic.

“I’m not saying my husband is perfect,” she says. “He’s obviously there for a reason, for something he did, and he’s got to serve his time. But at the same time, it’s rehabilitation.”

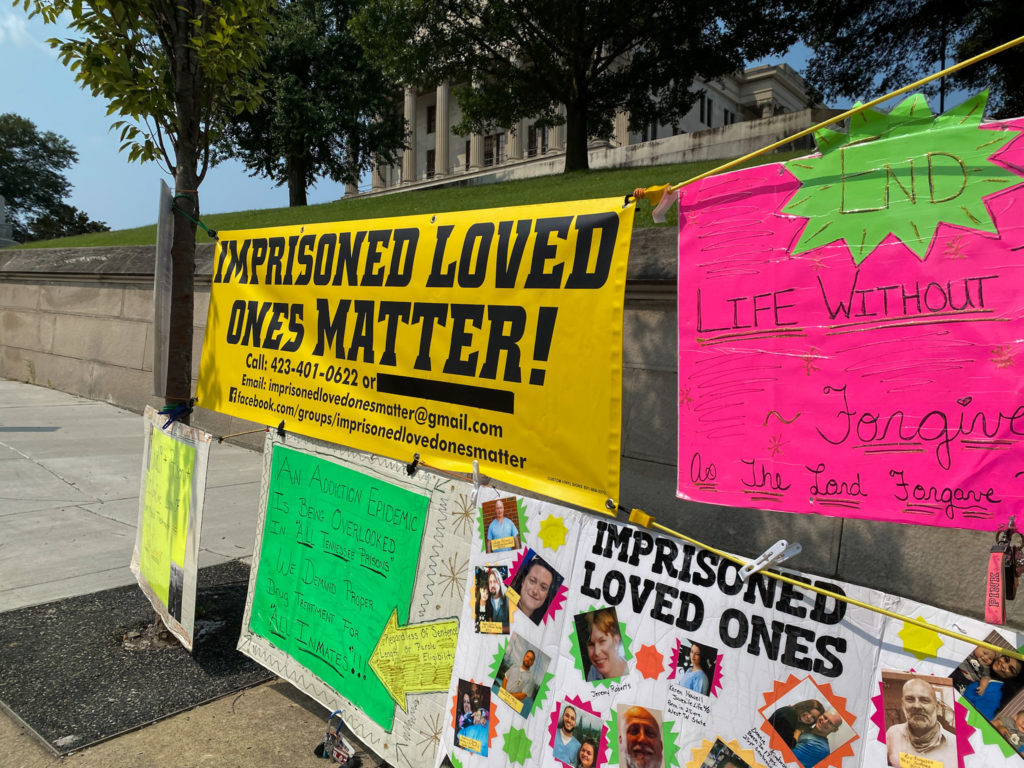

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsAt a protest in September, Shannon Young holds a sign featuring photos of her embracing her husband and the message, “I will fight for him and be his voice, even when they try to keep him silent.”

Young says the Department of Correction is supposed to correct bad behavior, not just lock people away without attending to their basic needs.

“You’re still responsible for their meals. You’re still responsible for their healthcare,” she says. “That’s their responsibility for someone in their care, and they’re not doing it.”

TDOC says COVID-19 has changed healthcare in its prisons, just like it has across the country. But the agency disputes that it has gotten worse. CoreCivic, the private company that manages South Central, says it’s following state directives and has worked to provide “a high standard of medical care.”

Both say they have systems in place to keep drugs out of their facilities. Multiple people have been arrested in the past year for bringing contraband into prisons, according to TDOC’s website.

But Young thinks officials aren’t doing enough to keep prisoners healthy. For months, she and a group of loved ones have spent most Fridays protesting outside of TDOC’s offices in downtown Nashville, beneath a flimsy, blue tent.

On one windy day, I had just asked Young what she loved most about her husband when a gust nearly toppled her whole setup. She chuckled with a hint of desperation and clutched a wobbly tent pole.

“Really just his will to go on, facing what he’s facing and not — not giving up,” she said. “He’s like, ‘You know, I’ve overdosed twice, I’ve tried to commit suicide once,’ and he’s like, ‘God hasn’t taken me, so, I must still have something else to do on Earth.’ ”

Unlike many prisoners’ loved ones, Young isn’t afraid to speak. Her husband was sentenced to life without parole, so she feels like she has nothing to lose.

But most prisoners are not condemned to death behind bars. And she hopes conditions will get better — not just for her husband — but for all those who have a chance to walk free.

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member.