Alongside some Tennessee roads, you might notice knee-high cement markers — usually quite weathered — that have this inscription: “H’Y. R.W.”

Marilyn Witko Rosinki noticed one. The hobby historian had just gotten off the bus and was walking to church when she noticed the low-down stone pillar just a couple feet off the sidewalk.

“But I couldn’t even figure out what the initials meant,” she says. “I was curious to learn if there are more around, and what the wording meant.”

She asked Curious Nashville to explain. And in picking up this research, that one little marker led us to a much bigger saga from Nashville history.

The little marker

Rosinki’s question first came in the same week that Curious Nashville was being featured at a meeting of the Nashville History Club.

She had a photo handy. In front of those history buffs, it was apparent that these cement markers are common.

Since at least the 1940s, they’ve marked property edges alongside major roads. And the inscription — “H’Y. R.W.” — is an antiquated abbreviation for Highway Right of Way.

Since at least the 1940s, they’ve marked property edges alongside major roads. And the inscription — “H’Y. R.W.” — is an antiquated abbreviation for Highway Right of Way.

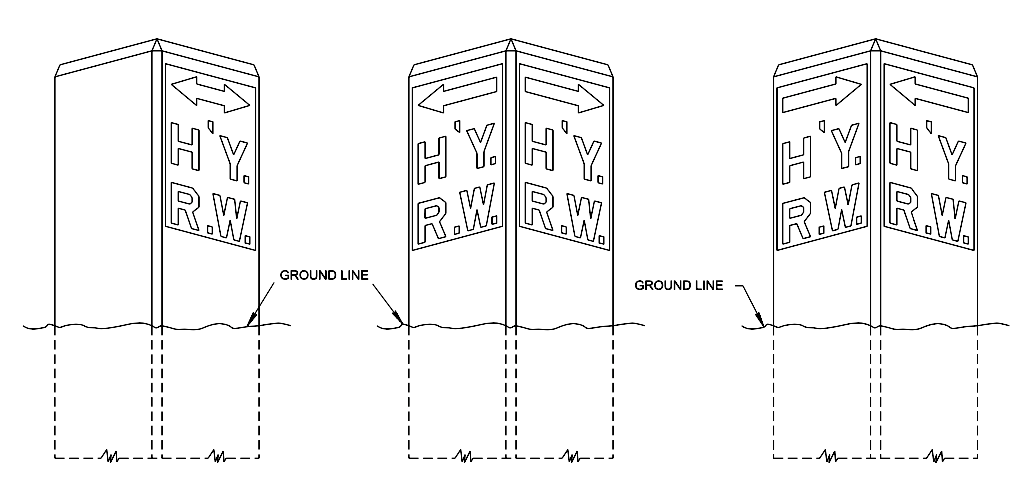

You can find these markers across Tennessee, and ever since the question came in, WPLN staffers have been noticing them. There’s one near GasLamp antiques at 100 Oaks. There are several along a trail in Montgomery Bell State Park. Online, the Tennessee Department of Transportation even has a schematic with the exact specs for how these markers should be made.

Rosinski noticed hers on Brightwood Avenue where it passes over Interstate 440 in Green Hills. That’s a notable spot, and it unlocks another local history mystery that’s been floated to Curious Nashville in the past.

Why so wide?

The Brightwood overpass is extra wide. It could seemingly fit six lanes of traffic, but instead includes a grassy lawn. The people want to know why.

One bicyclist put it this way to Curious Nashville:

It’s EXTREMELY wide and I’ve always wondered if there’s a story behind its construction!?

Another mused:

We like to think it was meant as a park that was scrapped when a frisbee went onto the highway.

These question-askers are onto something.

A public park was, in fact, part of the idea.

“And it was gonna happen, and then it just didn’t happen,” says Kem Hinton, a prominent local architect who worked on the idea in the 1980s.

But the saga dates back much further.

Let’s go back to 1927, when the city dedicated a towering sculpture. The Battle of Nashville Monument — also known as the Peace Monument — marked the spot where Union and Confederate forces first clashed in the city. It was at the 3-way intersection where, at the time, Franklin Road and Thompson Lane converged.

“As a youngster, I remember vividly … there was this incredible monument,” Hinton recalls. “It is a superb expression of reconciliation.”

Later, those roadways would undergo major changes, causing residents to want to relocate the monument.

Later, those roadways would undergo major changes, causing residents to want to relocate the monument.

And on April 1, 1974, a tornado toppled the giant obelisk and its figures and cracked the Italian marble base. (You can read an here account via The Nashville Retrospect.)

By 1983, as work progressed on I-440, residents began wondering why the Brightwood overpass was being constructed extra wide.

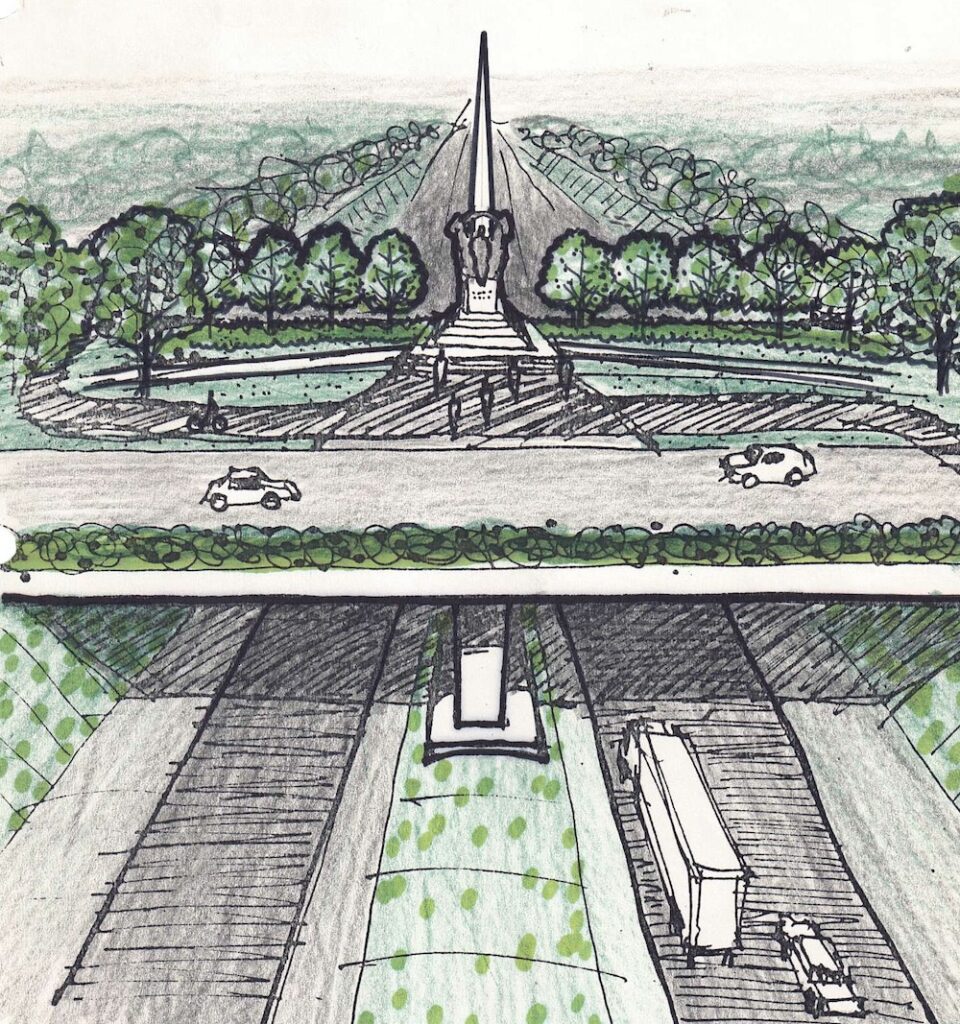

The plan: Relocate the Peace Monument to a special park plaza, affording it higher visibility.

“The memorial was to be placed on the northern edge of the overpass,” Hinton says.

If you’ve heard the “land bridge” concept in recent years, well, Brightwood was Nashville’s first, long ago. And, at that time, I-440 was envisioned as a more beautiful parkway — with no trucks allowed — compared to the loop highway that it has become.

Yet the monument did not end up on that overpass. Hinton recalls some concerns about inadequate sightlines for drivers on I-440. He also moved to a different firm.

Yet the monument did not end up on that overpass. Hinton recalls some concerns about inadequate sightlines for drivers on I-440. He also moved to a different firm.

By 1988, the debate was still underway, and multiple locations — Centennial Park, Fort Negley and the state capitol — had all been considered but rejected.

In 1992, the Tennessee Historical Commission settled on Granny White Pike, about a half-mile from Brightwood, and that’s where it remains today.

‘Masterpiece’

“It was a very noble effort at the time. But as time has gone by … it’s nowhere near as visible as, say, another location,” Hinton says.

In his experience, the “masterpiece” monument doesn’t get many visitors, and he still wishes it could find a more prominent home.

In his experience, the “masterpiece” monument doesn’t get many visitors, and he still wishes it could find a more prominent home.

Meanwhile, at least two remnants remain from the whole situation.

One: The original 1927 marble base — back on Franklin Road — actually still stands amid some overgrowth there. Hinton occasionally visits and wonders what could be done.

And two: Residents are left to forever wonder about that empty, extra-wide Brightwood overpass.