Boxes are crammed in Virginia Holland’s bedroom like a storage unit. Her family’s clothes spill out of anything that’ll hold them. A bassinet, trash bags, plastic containers.

She doesn’t use her closets, or rather, can’t.

Over many calls and visits, only one thing has made Holland perk up with pride. She pulls back the brown curtain from her window to show it off.

“I look out my window and see the view that people will pay thousands to see, which they will get the same opportunity eventually,” Holland says.

Peek into how redevelopment is redefining the city

From her bedroom window, you can see the Batman building, the Titans’ stadium and tons of cranes in the sky.

The future of Nashville is evident along the Cumberland River. Mayor John Cooper and the state are working hard on large spending commitments, like potentially giving the Titans’ Nissan stadium its own face lift and transforming the East Bank into a neighborhood including the billion-dollar Oracle tech campus.

Holland’s apartment complex is in walking distance of these large projects.

If you’ve ever sat in traffic on I-24 next to downtown, you’ve seen the Riverchase apartments. They are red, yellow and green buildings, and one by one, these affordable units are getting boarded up for redevelopment. But for years, the deterioration has been apparent to residents and even government inspectors.

Why didn’t the city do more? WPLN News has been investigating the conditions residents lived with

Developers have had their sights on Riverchase for a minute. In 2014, one bought it for $3.5 million dollars. Last year, the price tag jumped to $30 million, which is nearly 10 times more.

The new property owner is proposing an idea to develop thousands of apartments, retail and open space.

Holland has lived here since 2018. Unlocking the door to Apt. 644 was like unlocking a new chapter for her. That was until special guests introduced themselves — mice.

“That’s why all of this stuff sits out here,” she explains.

“You know, I don’t want to have to keep one in the closet and worry if something is going to jump out or fall out on me.”

There’s one time that’s seared in Holland’s memory.

“She had her babies on the sticky pad, and they were all pink and piled up, and it was so disgusting,” she says in disgust. “But I was more so grossed out at the fact because I had just had a newborn baby. So, like, they literally did something to me.”

The problem isn’t just Holland’s apartment

After requesting records, the Metropolitan Development and Housing Agency allowed WPLN News to review more than 1,600 reports in its office.

More: View a sample HUD inspection form.

Those reports show, from 2016 to October 2021, units failed inspections nearly half the time.

Evidence of infestation was just one complaint. Inspectors found 288 electrical hazards, 195 security issues and 255 bad ceiling conditions.

And when analyzing records of Holland’s unit, two failures, four passes and one inspection without a result show up. The inspector didn’t note the ceiling leaks, cracks around the window and mice problem in the apartment — something Holland had documented throughout her four years living at Riverchase.

The agency says the inspector didn’t see the problems and that Holland never reported them.

Since 2016, Elmington Property Management and Freeman Webb ran the complex for the owners

Records show when MDHA asked them to fix a problem, they did more than half the time. But in hundreds of cases, the problem still wasn’t fixed.

WPLN News reached out to Elmington Property Management for an interview and sent questions in writing. The company didn’t respond.

In a different situation, the Bedford County Listening Project alleges the company has temporarily moved residents to an infested hotel building and provided little communication.

“We could have the greatest intentions,” Freeman Webb’s Regional Property Manager Ken Britton says. “But if we don’t have the financial backing, then we can only do so much.”

Freeman Webb took over the property two years ago.

“I don’t think we really knew extreme details of the property,” he says. “We just know that it’s been very challenging for the previous company, and it definitely had a higher crime issue and certainly a deferred maintenance that has been for years and years and years. I mean, long before the previous property management company took that position, this property has had the reputation for 15, 20 years.”

The roof and windows were five to 10 years beyond when they should’ve been replaced. But since the owners knew they’d be demolished they decided to just do repairs.

Britton says crime in the area created hurdles for addressing residents’ concerns.

“We had difficulties keeping maintenance (especially in a job market where maintenance was already difficult to find) as well as maintenance staff having concerns working in the units alone and or after hours,” he tells WPLN News.

Freeman Webb got involved despite the property’s track record because they wanted to help transition current residents. Plus, the company was thinking about the potential long-term commitment after the demolishing and building of a new property.

Holland holds someone else accountable too

“This is the city’s problem,” she says. “How do you let people that’s on a housing program that’s offered by this city to fall through the cracks like this?”

Technically, it’s two different government agencies that are responsible for checking on the property’s conditions.

One is MDHA. But it only inspects apartments from tenants getting housing vouchers from them. Other residents would have to take their complaints to the city’s codes department.

The two mainly talk when there’s a major system issue.

“You know, a plumbing, electrical, things like that where we see a potential for codes violation under that circumstance,” MDHA’s Director of Rental Assistance Norman Deep says.

When WPLN News asked Deep how Riverchase compares to other affordable units around the city, he says it doesn’t stand out much. But MDHA hasn’t actually done this kind of analysis with the 724 privately owned properties it works with.

MDHA has limited power to hold owners accountable. For most issues, Deep says they have up to 40 days to show they’ve made repairs.

Ambriehl Crutchfield WPLN News

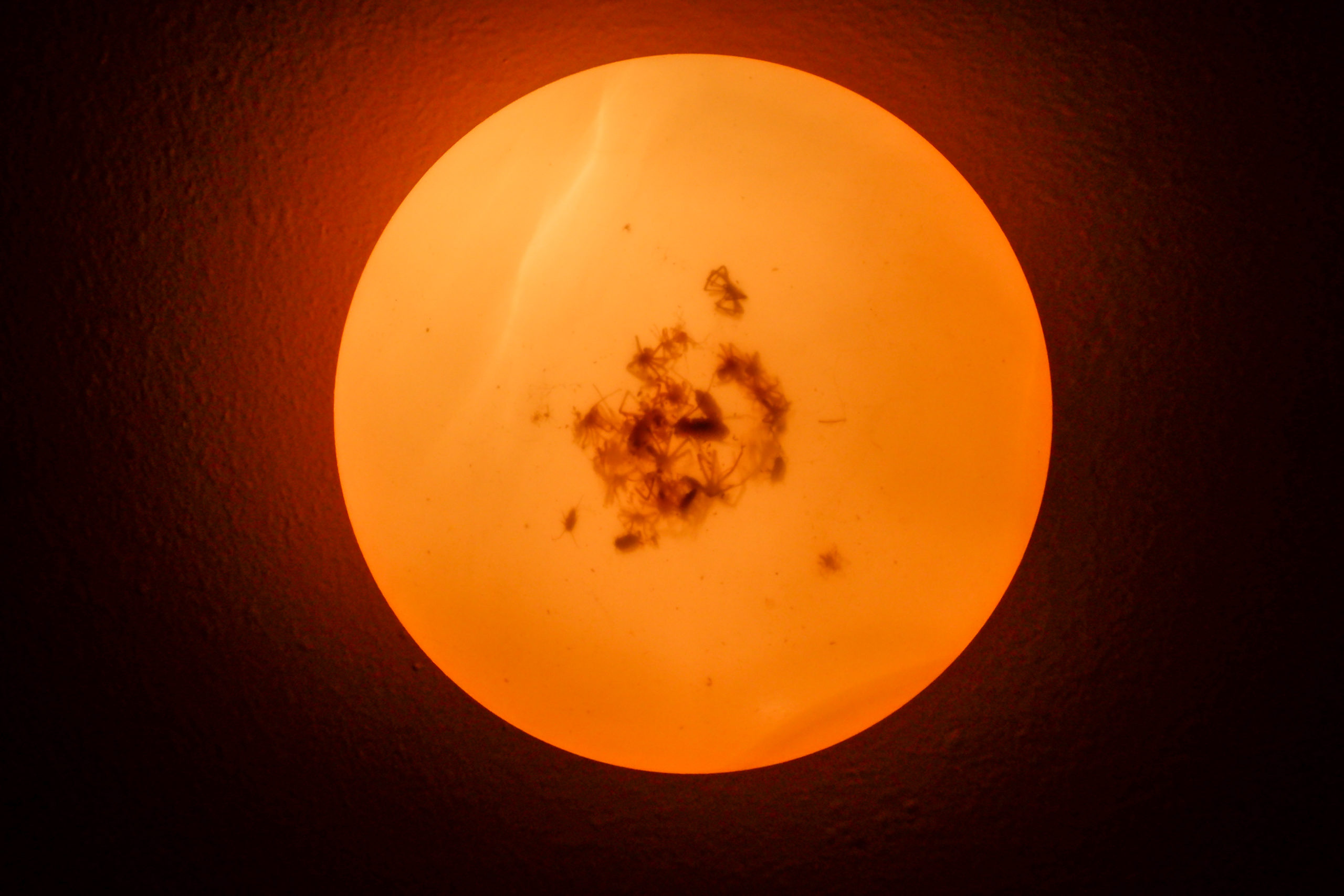

Ambriehl Crutchfield WPLN NewsThe ceiling light in Virginia Holland’s hallway displays a spider issue.

“And if they don’t, at that point, then we have to consider whether or not to terminate the contract,” Deep explains.

That means the renter is stuck with limited options to ensure they have a decent home that’s safe.

MDHA say they had to end some contracts. But they’ve only barred a company one time in the last three decades.

The Tennessean reported on the constraints the city’s codes department has in holding owners accountable.

In a hot real estate market, there’s little reward for owners to do costly repairs

For almost two decades, James Fraser has studied the city’s housing.

“Property owners are just choosing to sell if they’re put in a position to rehab,” he says. “The end result is that the people will be moved out if the infrastructure is deemed to be in such disrepair that it needs to be demolished.”

Since the land apartment complexes sit on have increased in value, either owners sell and make a large, one-time profit or they rehab units and charge what they want in rent, which is also known as market rate rent.

Fraser says codes enforcement is important. But he wants the city to revisit a bigger idea: researching how much money is needed for the city to develop its own housing.

Fraser suggests the city would need to take out a general obligation bond, or a loan that a government takes out, of at least a billion dollars.

“While the city would engage the private sector in producing this housing, which benefits many constituencies, the management of the community land trust needs to be done by multiple nonprofit housing groups that already exist in the city,” he explains.

That’s the only way he sees safe living conditions being prioritized over making money.

If you dig through the last few years of housing reports, the idea of a community land trust is one the city was told about back in 2014. That was four years before Virginia Holland started feeling trapped at Riverchase.

This is Part 1 of WPLN’s series, Displaced. Next, we’ll look at what’s being done to help residents move — and the tensions that have arisen. That story is coming up next Wednesday and can be found on the series landing page — as well as an explanation of how this investigation was reported — here.