Fast bus service, 86 miles of sidewalks and a dozen new transit centers — those are some elements of Mayor Freddie O’Connell’s freshly unveiled transit improvement proposal.

O’Connell announced in February that he would pursue a transit referendum this fall, asking Nashville voters to dedicate a share of tax dollars specifically to transit and transportation. Details of the Nov. 5 ballot measure were not immediately released at that time, setting in motion a series of public meetings to shape the proposal.

Now, after two months of planning — which included the convening of advisory committees, meeting with members of the Metro Council, and drawing upon dozens of prior planning efforts and 65,000 pieces of input from the community over the past decade — O’Connell has unveiled what the plan will fund, and how it will do so.

“This is the best opportunity we’ve ever had to build out our priority sidewalks, to synchronize signals so you’re spending less time at red lights, and to connect neighborhoods via a better transit system that doesn’t have to come downtown just to go somewhere else,” the mayor said. “This is about the sustainability of our workforce and this community, and how we bring the cost of living down so that our residents can afford to live here.”

More details and interactive maps are online at nashville.gov/transit.

In all, the proposal’s total cost, as outlined in the plan, is estimated at close to $3.1 billion over the decades that it would take to implement.

Increased service

The plan’s release contained few substantial surprises, remaining in line with much of what has been presented to advisory committees.

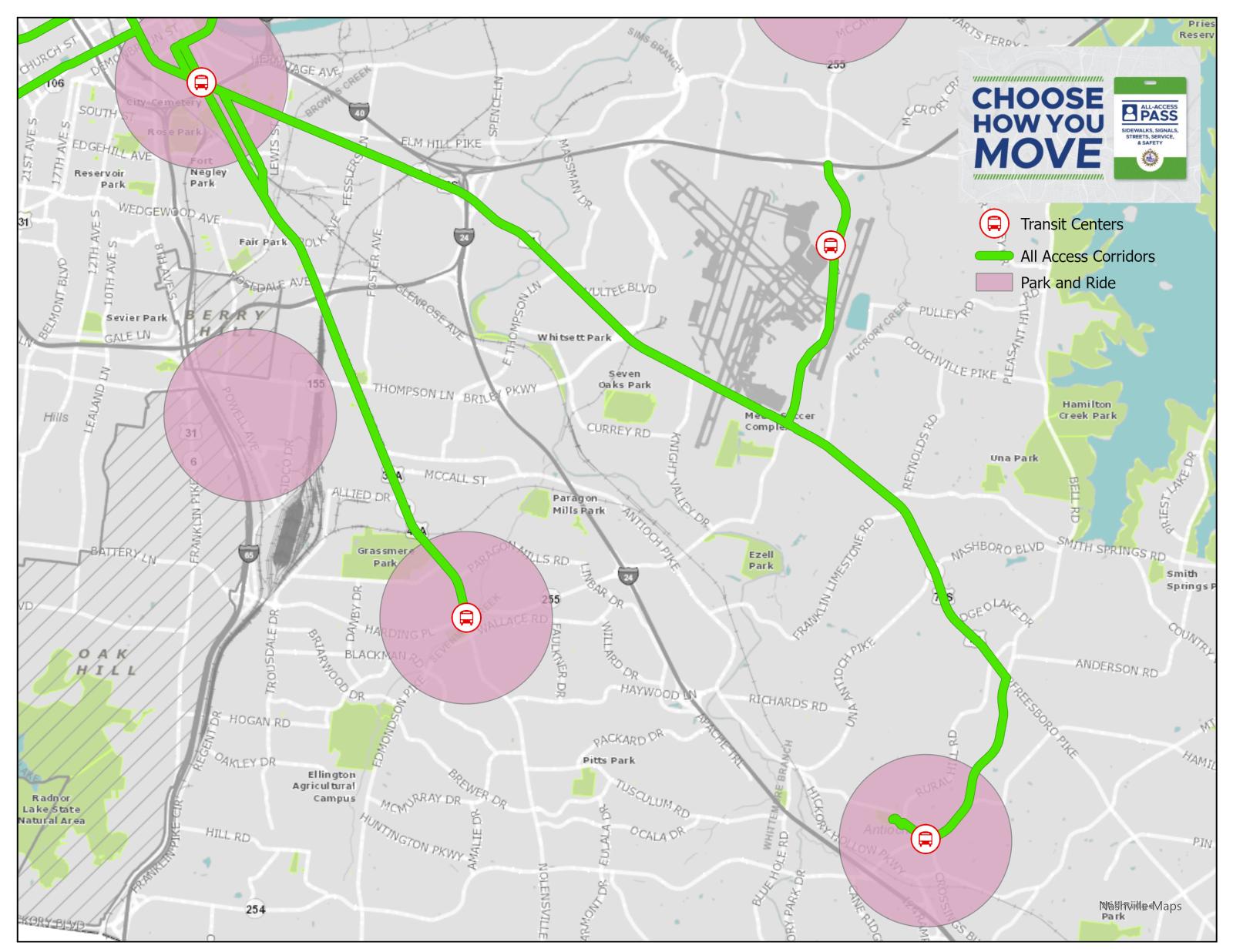

A cornerstone is what Metro is calling “all-access corridors,” which are upgrades to Nashville’s most heavily-traveled routes. These will include increased service — transit would run every 15 minutes for longer hours — and high-frequency bus lines. This high-frequency daily service would be doubled, and overall, bus service would increase by 80%.

In some areas, there will be routes for Bus Rapid Transit — a system that can include things like dedicated lanes only for buses, traffic signal priority that gives buses an advantage in traffic, and off-board fare collection and elevated platforms to help the buses start and stop more efficiently.

In the plan, the all-access corridors will be established in ten locations: Murfreesboro Pike, Gallatin Pike, Dickerson Pike/East Bank Corridor, Nolensville Pike, West End, Downtown (in three spots — Westside, East Bank and James Robertson), Charlotte Pike, and Bordeaux/Clarksville Pike.

The plan also would also expand Nashville’s transit hubs, establishing a network of a dozen new transit centers across the city. Currently, Nashville only has three (the downtown Elizabeth R. Duff Transit Center, Hillsboro Transit Center, and the not-yet-open North Nashville Transit Center). The city currently relies mostly on simple bus stops, which occasionally have benches or overhead coverings — and most routes are oriented toward the downtown hub.

Other highlights of the plan will include:

- 17 Park and Ride facilities, each complete with 100-200 parking spaces

- Increase in crosstown connector routes

- Four new express bus routes

- Increased regional bus service and expanded WeGo Star commuter train service

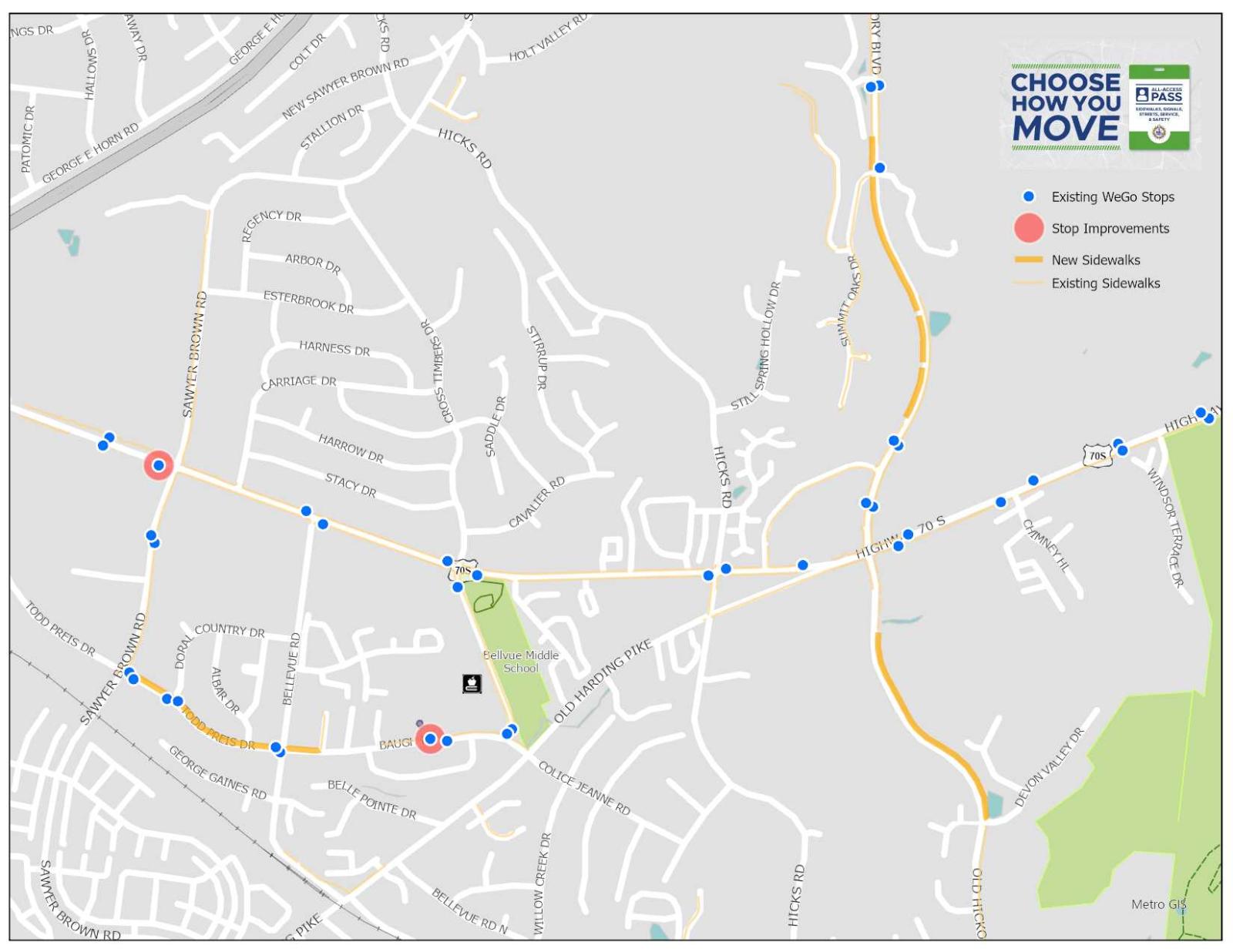

- Improvements to 285 bus stops

Part of Metro’s interactive service map, showing Murfreesboro Road.

Sidewalks, service and safety

A signature element of O’Connell’s plan is that it doesn’t solely focus on Nashville’s public transit — rather, it also features improvements for drivers and pedestrians.

This means funding 86 miles of sidewalks — which, combined with the annual capital spending plan’s sidewalk budget, would complete the priority sidewalk network outlined by WalkNBike. It would also update traffic signals on the busiest corridors. There would also be 39 miles of “Complete Streets,” where streets are built for pedestrians, bikers, buses and cars. Much of this is geared toward safety; those 39 miles are along Nashville’s high-injury network and are geared toward reducing rates of traffic and pedestrian deaths.

The program would fund updates to nearly 600 traffic signals. They would tie into a new Traffic Management Center, where NDOT can monitor traffic and adjust signals in real-time to improve delays.

“Everyone should know that they’re safe when using this system and accessing the city,” O’Connell says. “Put it all together and this is how we catch up on our transportation to-do list in a big way.”

Part of Metro’s interactive sidewalks map, showing Bellevue.

Costs and financing

In total, the plan is estimated to cost $3.096 billion over a lengthy rollout period.

The O’Connell administration is waiting to release definite numbers, as the administration awaits an independent financial audit. At that time, they will release the initial cost of construction, as well as the number associated with the longer-term creation and operation of the program.

The plan asks voters to approve a half-cent sales tax increase to cover a large share of the costs. That would generate more than $100 million per year.

However, the administration has said the improvements will not be entirely reliant on the sales tax — rather, approving this local source of funding will make Nashville eligible for a greater swath of federal dollars. Oftentimes, these federal funds are reliant on a local match — which, without dedicated transit funding, Nashville usually has been unable to provide. The plan identifies as much as $1.4 billion of federal dollars that the city could access after establishing a reliable source of local funding.

Under the IMPROVE Act — the law that allows local governments to devote a portion of taxes specifically to transit if approved by voters — there are six types of taxes that could be used.

O’Connell’s administration has said that the selection of solely a sales tax increase is because it is the highest-revenue potential option. Nationally, a sales tax surcharge is the most common type of local transit tax. The plan makes the case that about 60% of Nashville’s sales tax is paid by visitors.

The half-cent increase would bring Davidson County up to the maximum 9.75% rate. The majority of this — 7% — already goes to the state. Currently, the city receives the remaining 2.25%. The referendum would tack on more to directly fund transit.

Most of Davidson’s surrounding counties — Robertson, Rutherford, Williamson and Wilson counties — are already at this maximum rate.

The O’Connell administration says that the half-cent increase would amount to an average of an additional $70 per year for most Nashvillians.

“The amount of benefit we get, if I know I’m going to have easier access to a school, park, library, grocery store, small business in my community … is going to make the cost palatable,” O’Connell said.

How does it compare to the 2018 plan?

The last — and only — time residents were asked to consider establishing a dedicated tax for transit was in 2018. The proposal, introduced by former Mayor Megan Barry, looked drastically different from O’Connell’s approach — and ultimately failed when put to voters.

The cost (and scope) of the 2018 plan was considerable. The $8.9 billion plan (the cost associated with construction and operation for 15 years — capital costs were calculated at $5.4 billion) would have funded five light rail lines, a tunnel and transit station beneath downtown and a range of bus service improvements.

Before his announcement, many wondered whether O’Connell would include light rail in his proposal, which costs about $200 million per mile to build. In contrast, bus rapid transit costs around $48 million per mile.

Another major difference is the taxation approach. In 2018, the proposal would have seen increases to four different taxes: sales tax, hotel occupancy tax, business tax and local rental car tax. This was believed to be a sticking point for some opponents — and may have influenced O’Connell’s decision to only pursue a single surcharge.

What comes next?

The financial components of the plan are still undergoing a third-party audit and will also be reviewed by the state. And before the plan goes to voters, it is also subject to Metro Council approval.

The council process could play out between June and August. The administration has met with 36 members of the 40-member body, and is holding a special-called meeting with the entire council this week.

District 24 Councilmember Brenda Gadd says she feels hopeful that the council will approve the plan.

“We’re an inquisitive bunch — but I look forward to learning more,” Gadd says. “I do feel very confident the council will approve this, and we can get it directly to the voters as quickly as possible.”

Some local groups have already expressed their support of the plan. Members of Nashville Organized for Action and Hope, or NOAH, were present at the announcement and expressed their support, while calling for provisions to address the regressive nature of the sales tax.

A representative of the Central Labor Council of Nashville, Ethan Link, also spoke in support.

“Safe, reliable and affordable transit isn’t just a matter of dollars and cents. It’s not just a matter of modes and routes,” Link said. “It’s about the dignity of not walking in the mud, worried that you’re going to be late dodging vehicles just to get to the bus stop. Working families deserve better.”

The public referendum is scheduled for Nov. 5. If voters approve, the city says the new tax collections would begin on Feb. 1, 2025.

The plan calls for some changes to begin immediately and suggests that, within two years, the city would see “substantial” bus service improvements and progress on sidewalks and signals.

The full horizon of changes extends more than 15 years into the future.