Tracy O’Neill loves sitting under her crabapple tree, shaping flower necklaces from homegrown daisies and chatting with her neighbor, who occasionally pulls up on a tractor.

She lives with her seven-year-old son in rural Ashland City. A giant stone Buddha head commands her yard, which boasts a wildflower field, a toy ATV and sylvan borders humming with insects and birds.

“I come out here and it’s quiet,” O’Neill said. “It’s beautiful, and it’s like my sanctuary.”

In the front of her home, there are signals of the change about to come: Orange “No TVA Pipelines” and “Protect our Community” signs line her driveway.

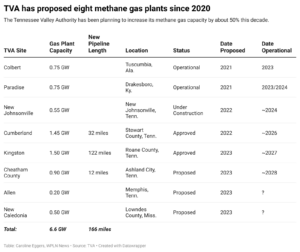

The Tennessee Valley Authority has been rapidly expanding fossil fuel infrastructure across the region and is on track to construct eight methane gas plants by the end of the decade. The buildout is part of a fossil fuel system that starts with fracking and ends with burning — a system that affects the planet and can harm the health of people living nearby.

O’Neill and her son will be on the fenceline of some of the resulting pollution: TVA has designs for a gas plant and a 12-mile pipeline in Ashland City. O’Neill does not know what that means for their health yet.

“I have a good heart right now,” she said. “I’d kind of like to keep it that way.”

TVA, she added, has not provided any clarity.

How gas infrastructure impacts health

Gas is a fossil fuel. The industry calls it natural gas, but it has become standard to call gas by its main ingredient: methane. This is the same gas that possibly heats your home and your stove.

To use methane for electricity, there has to be drilling, transport across pipelines, burning at compressor stations, and then burning at big turbines.

The combustion stages release a lot of carbon dioxide, along with toxic air pollution like nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds like benzene and formaldehyde.

“These are known to have carcinogenic, neurologic and respiratory effects,” said Karen Knee, an environmental scientist at American University who has studied how oil and gas activities affect freshwater supplies.

Air pollution from gas extraction, transport, and combustion can disperse broadly, but its effects are usually greatest near or downwind of the source.

Local impacts are challenging to study, however, as it takes a long time to connect specific health impacts to a singular source of outdoor air pollution. In the U.S., this slow epidemiology has translated to dangerous situations for people living near industrial facilities.

“Unlike a lot of countries in Europe that go by the precautionary principle,” Knee said, in the U.S., “it’s like we’re going to expose people to it, and then you have to document that there’s harm and this is what caused it.”

For gas plants specifically, some experts say answers may lie upstream.

From upstream to downstream

Pennsylvania has been an ongoing case study for the dangers of exposure to methane gas. In the early 2000s, fossil fuel companies expanded gas extraction with fracking, which involves drilling down and then horizontally into rock — that can be as much as 500 million years old — using massive amounts of water.

By 2011, the U.S. became the top global producer of gas, overtaking Russia, and the volume extracted has since increased. Last year, the nation set a new record for gas production, with a monthly average more than 60% higher than in 2011.

Communities living near the fracking boom have been harmed throughout the process. Now, nearly two decades after fracking ramped up in Pennsylvania, the science is proving that.

In 2022, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh found that children living within a mile of a fracked gas well were seven times more likely to develop lymphoma, a rare form of cancer, than children who had no wells within five miles of their homes. That same year, Harvard University researchers found that the closer people over 65 lived next to an oil and gas operation, the higher their risk of dying prematurely, even accounting for socioeconomic, environmental and demographic factors.

“The health impacts are anywhere from headaches and cognitive issues all the way to cancer,” said Christina DiGiulio, a chemist with the Pennsylvania chapter of the Physicians for Social Responsibility. “You see children with nosebleeds.”

DiGiulio studies pollution from gas infrastructure through thermography, a practice of using special cameras to see the invisible. She has imaged many fracking sites and compressor stations — and, lately, she has been imaging gas plants.

“We call it a system for a reason,” DiGiulio said. “Through midstream, downstream and upstream, we’ve seen the same thing.”

Health risks from pipelines and compressor stations

After fracking, the industry sends gas through pipelines divided by compressor stations. Compressor stations pressurize the gas as it travels, often, across multiple states to its destination. Tennessee likely attains much of its gas from Pennsylvania and other states holding the Marcellus Shale, the largest source of gas in the U.S and possibly the third-largest source of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The gas flowing through pipelines, which have detectable levels of pollutants like benzene, can escape into the air. One study found that leaky distribution pipelines in cities may increase the concentration of methane in soil and kill urban trees.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News (File)

Caroline Eggers WPLN News (File)Tracy O’Neill has signs in front of her house in Ashland City, Tennessee on May 2, 2024.

Compressor stations are known to release about 70 air pollutants, 39 of which are linked to cancer. In 2020, a study linked proximity to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from compressor stations to higher death rates. Despite the expansion of gas drilling in the U.S., “studies of human health in association with compressor stations are almost completely absent from the literature,” the researchers wrote. In 2021, a study found “alarming levels” of VOCs inside homes near compressor stations in Ohio.

This infrastructure also carries a risk of explosions. Between 2003 and 2024, gas pipelines caused 222 fatalities and about 1,000 injuries. Compressor stations can also ignite. A station on Kinder Morgan’s Tennessee Gas Pipeline — which will be connected to TVA’s Cumberland and Ashland City projects — exploded in Hickman County last year.

Burning at gas plants

The final stop in the gas system, for electricity, is burning at big turbines. This combustion produces nitrogen oxides and VOCs, which can react with other things in the air to form particulate matter and smog.

There are some studies that document how gas plants harm people locally. In Florida, researchers found that pregnant women living near plants were more likely to give birth prematurely. In Italy, gas plants that produced nitrogen oxide levels within federal limits were connected to increased medical emergencies among elderly people.

But there is not much research on the local health impacts of gas plants, perhaps for the same reason that the health risks of fracking, and even gas stoves, are only now being communicated to the public: It can take a long time to document harm. That allows the fossil fuel industry to delay responsibility, DiGuilio said.

“I feel like they exploit that,” DiGiulio said. “How the industry postures, it is quite a PR scheme.”

Researchers might be nearing a turning point, however. While a lot of gas infrastructure is quite new — gas accounted for a little under one-fourth of U.S. electricity in 2010 — it is growing in use. Last year, gas accounted for nearly 43% of electricity generation.

What does TVA say about public health?

When asked how the new gas plants, compressor stations and pipeline segments would affect the health of people living near them, TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks directed WPLN to the pipeline companies.

“We are customers of the current and proposed pipelines. Those discussions are best directed to the owners of the pipelines,” Brooks said in an email.

When asked again, he said state and local health departments were the “best source” for public health questions. He said TVA considers the environmental impacts of projects through environmental reviews and follows all rules and regulations.

“The health and safety of the public is always our priority,” Brooks said.

According to one federal agency, however, TVA has been trivializing the expected pollution from its planned gas buildout.

EPA faults TVA’s math on pollution

In March, the Environmental Protection Agency faulted the federal utility’s environmental review for its now-approved Kingston project in a letter. TVA underestimated the expected planet-warming emissions and conventional air pollution that would be caused by the project, according to EPA.

More: ‘Misleading’: EPA lambasts TVA analysis for Kingston methane project | WPLN News

TVA also overestimated some of the emissions reductions associated with replacing coal with gas. The utility requested permits from the state of Tennessee that allow increases in several pollutants, including nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds and greenhouse gas emissions, after coal retirement.

The “allowable emissions” TVA requested in state permit applications were higher than the utility suggested was needed in the environmental review for the Kingston project. “The total [nitrogen oxide] emissions estimated in the…analysis are just 178.8 tons per year, whereas the allowable emissions requested in the permit application are 1,456 tons per year,” EPA wrote.

TVA also used outdated calculations for the social cost of climate pollution, which EPA wrote is “misleading to decision-makers and the public as it depicts a skewed and incomplete picture of the scope of environmental impacts.”

A “No TVA Power Plant in My Yard” sign sits on a property in Ashland City, Tennessee on May 2, 2024.

The next few decades of fossil fuels

Air pollution from burning fossil fuels was estimated to cause between 9% and 20% of all deaths on Earth each year before the COVID-19 pandemic. Fossil fuel use also causes the overwhelming majority of climate pollution, and climate change affects health in so many ways, from heat and extreme weather to higher risks for pandemics and disease.

The fossil fuel expansion across the Tennessee Valley will impact the health of people for as long as there is combustion.

For many folks in the region, the gas plants are being built in communities that have long suffered the impacts of coal burning.

For O’Neill and other residents in Ashland City, there are a lot of unknowns.

But one thing is for sure: the anxiety of living next to a gas plant has already impacted her mental health.

“I cry,” she said, “because it’s not supposed to be here.”