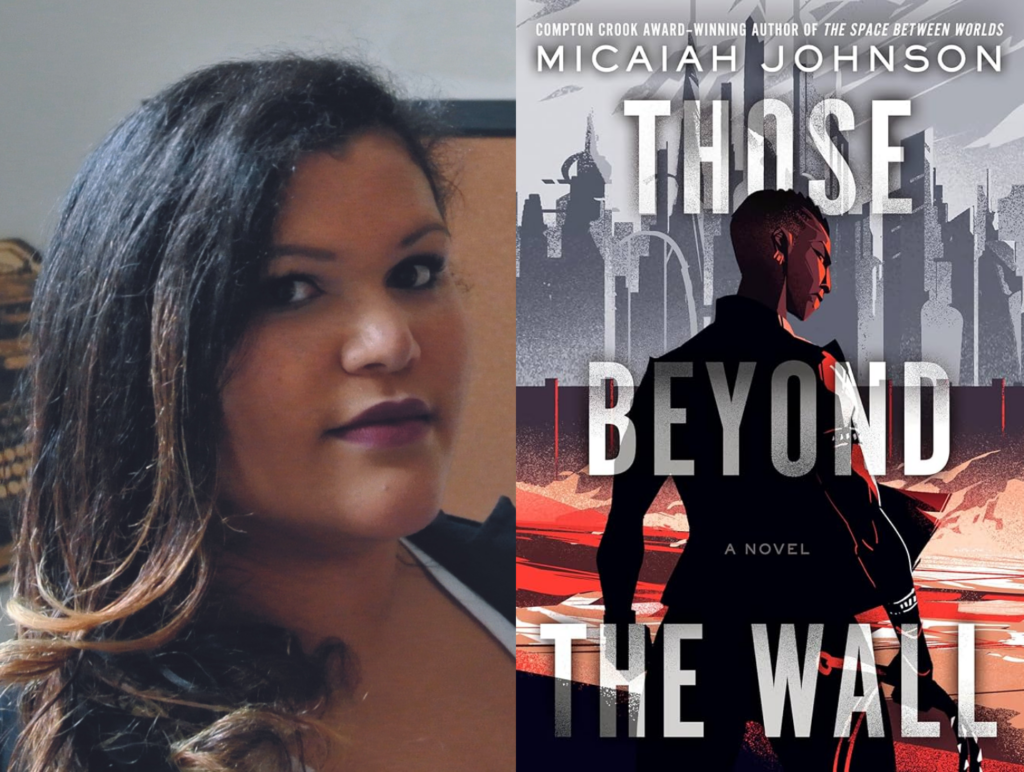

Award-winning author and Vanderbilt University scholar Micaiah Johnson became a new voice to watch for her debut novel, The Space Between Worlds. In an Earth wrecked by climate change, the wealthy take refuge in a city with an artificial atmosphere, leaving the rest of the population to survive in the desert.

Now, Johnson is returning to that world in a new sequel, Those Beyond the Wall, out today.

WPLN’s Marianna Bacallao sat down with Johnson ahead of the release of her sophomore novel.

Micaiah Johnson: Thank you for having me. I’m so excited.

Marianna Bacallao: Now, I’ll confess. I’m a big fan. I loved the Space Between Worlds, and when I saw in the acknowledgements that you were studying at Vanderbilt, I knew I had an excuse to talk to you.

In this sequel, I was struck by how much of Nashville, and the politics of the last few years, made it into this novel. You start the book with a shoutout to the People’s Plaza, which was the 62-day protest at Legislative Plaza after the killing of George Floyd. Can you tell me about that experience, and how it affected your writing?

Johnson: The People’s Plaza is all over this book. I dedicate it to them because, like, these were not just my friends, but we were in such intense situations together. We were in violent arrest together. There are so many experiences that we have had that nobody else can understand.

Bacallao: You’ve been vocal about the moments of joy during the People’s Plaza, and there’s a similar thread in your novel, in that those living outside the city have a much stronger sense of community and duty to take of each other than those inside the city. How does that hope persist in the face of great violence?

Johnson: Joy, for me, is another kind of another word for community, right? And I think it’s a lot to photograph, you know, Black pain. There are photos of me being dragged down steps. There are photos of my friends being arrested and having knees on their necks and all of these things, and that’s what I think is spectacular and people gravitate towards. But that is only fueled by those moments of dancing.

Those are the moments where it’s like, this is what it is all for. It is community. We hold each other up. And part of that has to do with an income difference. I feel like the further up you go on a power scheme or a power level, the more likely it is that you rely upon money to solve problems, right? If you need somebody to watch your kids, you pay for somebody. If you need new clothes, you buy them, all of these things.

Whereas at the level in which, you know, I am from, and many people at the Plaza were from, if you need to crash on a couch, it’s your friend’s couch. If you need somebody to watch your kids, it’s somebody whose kids you’ve watched before … Necessity breeds this community, and it really does breed this kind of love.

Bacallao: In your novel, the city prides itself on appearing progressive, on caring about human and environmental rights, at least inside its walls, but we also meet a transgender woman who left the city for the desert because she found a more accepting community there. What inspired her story?

Johnson: It’s very often easy for people to aim down, right? They want to aim at the poor in which they see hate as very explicit. But so often, those are people who are victims of the system as well, right? Their education systems have been defunded. They have had lead in their water. They have also been kind of a victim of the system, even though they are like kind of violently upholding it.

Whereas for a lot of progressives, it is their comfort that has allowed them to exist in a way that kind of covers over their hate and makes it very polite, but doesn’t make them any more welcoming to that which they deem kind of an unnatural, right? And so that’s why I kind of wanted to situate it there, because these are people with all kinds of power and all kinds of opportunity. What you really need is the desire to be open in the desire to change, and that’s not always present.

Bacallao: We’ve talked a lot about the larger systems that are at play in your work, but at the end of the day, it’s a first-person story, and so much of what we the audience see is through the perspective of a protagonist who is angry and jaded, but also a girl who wants to be loved. Why was her story so important to center for you?

Johnson: It was hugely important after The Space Between Worlds, in which I told the story of someone from the outside who wanted to be in the city navigating that space. It was hugely important for me to then tell the story of somebody who had no desire to be in the city.

No one person has a clear vision of any place. And that is true as much with Scales as it was with Cara. But it was important for me to show that multiplicity of viewpoints and those multiple ways of approaching the desert, you know, even having left it and vowing never to return when I did, I still have so much love for the place where I’m from. And there’s still so much uniqueness that I haven’t been able to find anywhere else.

Micaiah Johnson’s newest book, Those Beyond the Wall is out today. She will be at Parnassus Books on March 15 at 6:30 p.m. to talk more about her sophomore novel.